Buckle

The buckle or clasp is a device used for fastening two loose ends, with one end attached to it and the other held by a catch in a secure but adjustable manner.[1] Often taken for granted, the invention of the buckle has been indispensable in securing two ends before the invention of the zipper. The basic buckle frame comes in a variety of shapes and sizes depending on the intended use and fashion of the era.[2] Buckles are as much in use today as they have been in the past. Used for much more than just securing one’s belt, instead it is one of the most dependable devices in securing a range of items.

Historical background

The word "buckle" enters Middle English via Old French and the Latin buccula or "cheek-strap," as for a helmet. Some of the earliest buckles known are those used by Roman soldiers to strap their body armor together and prominently on the balteus and cingulum. Made out of bronze and expensive, these buckles were purely functional for their strength and durability vital to the individual soldier. The baldric was a later belt worn diagonally over the right shoulder down to the waist at the left carrying the sword, and its buckle therefore was as important as that on a Roman soldier’s armor.[3]

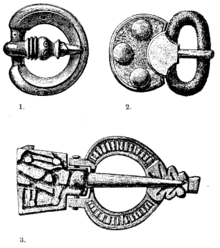

Bronze Roman buckles came in various types. Not only used for practical purposes, these buckles were also decorated. A Type I Roman buckle was a “buckle-plate” either decorated or plain and consisted of geometric ornaments. Type IA Roman buckles were similar to Type I buckles but differed by being long and narrow, made of double sheet metal, and attached to small D-shaped buckles (primarily had dolphin-heads as decorations). Type IB “buckle-loops” were even more similar to Type IA buckles, only difference being that instead of dolphin-heads, they were adorned with horse-heads. There were also Type II buckles (Type IIA and Type IIB) used by Romans, but all types of Roman buckles could have served purposes for simple clothing as well, and predominantly, as a military purpose.[4]

Aside from the practical use found in Roman buckles, Scythian and Sarmatian buckles incorporated animal motifs that were characteristic to their respective decorative arts.[5] These motifs often represented animals engaged in mortal combat. These motifs were imported by many Germanic peoples and the belt buckles were evident in the graves of the Franks and Burgundies. And throughout the Middle Ages, the buckle was used mostly for ornamentation until the second half of the 14th century where the knightly belt and buckle took on its most splendid form.[6]

Buckles remained exclusively for the wealthy until the 15th century where improved manufacturing techniques made it possible to easily produce a cheaper molded item available to the general population.[7]

Components

The buckle essentially consists of four main components: the frame, chape, bar, and prong. The oldest Roman buckles are of a simple "D"-shaped frame, in which the prong or tongue extends from one side to the other. In the 14th century, buckles with a double-loop or "8"-shaped frame emerged. The prongs of these buckles attach to the center post. The appearance of multi-part buckles with chapes and removable pins, which were commonly found on shoes, occurred in the 17th century.

Frame

The frame is the most visible part of the buckle and holds the other parts of the buckle together. Buckle frames come in various shapes, sizes, and decorations. The shape of the frame could be a plain square or rectangle, but may be oval or made into a circular shape. A reverse curve of the frame indicated that the whole buckle was intended to be used for securing a thick material, such as leather. This reverse curve shape made it easier to thread the intended thick material end over the bar. But the shape of the frame is not limited to simply squares and ovals, the decoration of the frame itself defines the shape it will turn out to be. Since the frame is the largest part of the buckle, any and all decorations are placed on it. Decorations range from wedged shapes, picture references to people and animals, and insignia of a desired organization.[2]

The part of the frame that strap goes through prior to putting the tongue/prong through the hole is often referred to as the 'end bar'. The 'center bar' holds the tongue and the part (if present) that holds the tip of the strap in place is called the 'keeper' or 'keeper bar' these terms are used when additional information is needed to describe a buckle for measurements or design. Note that if a separate piece of leather or metal is attached to the strap for holding the tip of the belt/strap in place that is sometimes also called a 'keeper'.

Chape

Chapes or "caps" of various designs could be fitted to the bar to enable one strap end to be secured before fastening the other, adjustable end. This made buckles easily removable and interchangeable, leading to a significant advantage since buckles were expensive.[2] Unfortunately, the teeth or spikes on the semi-circular chapes damaged the straps or belts, making frequent repairs of the material necessary. Buckles fitted with "T"-, anchor-, or spade-shaped chapes avoided this problem but needed a slotted end in the belt to accommodate them.[8]

Prong

The prong is typically made out of steel or other types of metal. In conventional belts, the prong fits through the buckle to secure the material at a pre-set length.[9]

The prong is usually referred to as the tongue of the buckle in America, as in 'lock-tongued buckle'. Prong is only used when the tongue is permanently fixed in position.[10]

Bar

The bar served to hold the chape and prong to the frame. When prongs and chapes are removed from the buckle design, the buckle incorporated a movable bar relying on the tension of the adjusted belt to keep it in place.[11]

Materials

Metal

The first known buckles to be used were made out of bronze for their strength and durability for military usage.[12][13]

For the last few hundred years, buckles have been made from brass (an alloy of copper and zinc). In the 18th century, brass buckles incorporated iron bars, chapes, and prongs due to the parts being made by different manufactures. Silver was also used in buckle manufacturing for its malleability and for being strong and durable with an attractive shine. White metal, any bright metallic compound, was also used in all styles of buckles; however, if iron was present, rust will form if it is allowed to be exposed and remain in damp conditions.[14]

Pearl

Pearl buckles have been made from pearly shells and usually for ladies’ dresses. Since a reasonable size flat surface was needed to make a buckle, oyster was commonly used to make these types of buckles. The quality and color of course vary, ranging from layers of yellow and white to brown or grey.[15]

Wood

When preferred materials were scarce during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the two World Wars, buckles became a low priority and manufactures needed to find ways to continue to produce them cheaply. Makers turned to wood as a cheap alternative since it was easily worked by hand or simple machinery by impressing the designs onto the wood. But there were problems using wood. Any attempt to brighten the wood’s dull appearance with painted designs or plasterwork embellishments immediately came off if the buckle were to be washed.[16]

Leather

Buckles were not entirely made out of leather because a frame and bar of leather would not be substantial enough to carry a prong or the full weight of the belt and anything the belt and buckle intend to support. However, leather (or dyed suede, more common to match a lady’s garment color) was used more as a “cover-up” for cheap materials to create a product worthy of buying.[17]

Glass

Buckles were not made out of glass; rather the glass was used as a decorative feature that covered the entire frame of a metal buckle. One method of creating glass buckles was gluing individual discs of glass to the metal frame. Another more intricate method was to set a wire into the back of a glass disc, and then threading the wire through a hole in the fretted frame of the buckle. The glass was further secured by either bending it over the back of the frame or splayed out like a rivet.[18]

Polymers

.jpg)

Celluloid, a type of thermoplastic invented in 1869, was used sparingly and only for decoration until after World War I where it began to be produced on a wider commercial scale. After World War II, the chemical industry saw a great expansion where Celluloid and other plastics such as Casein and Bakelite formed the basis of the buckle-making industry.[19] Many thermoplastic polymers such as nylon are now used in snap-fit buckles for a wide variety of applications.

Types of buckles

Clasp (Clearing up some disambiguation)

Although any device that serves to secure two loose ends is casually called a buckle, if it consists of two separate pieces with one for a hook and the other for a loop, it should be called a clasp. Clasps became increasingly popular at the turn of the 19th century with one clear disadvantage: since each belt end was fixed to each clasp piece, the size of the belt was typically not adjustable unless an elastic panel was inserted.[20]

Buckle trim or slide

A buckle without a chape or prongs is called a buckle trim or slide. It may have been designed this particular way or it may have lost its prongs through continuous use. This type was frequently used in home dress-making (belt end being secured with the simple hook-and-eye) and was purely used for decoration for items such as shoe fronts to conceal unattractive elastic fitting.[8]

Conventional (or belt buckle)

The conventional buckle with a frame, bar and prong gives the most reliable and easy-to-use closure for a belt. It is not meant, by design, to offer much space for decoration, but for its time-tested reliability.[8]

Side release buckle

A conventional buckle that is formed by a male buckle member (the hook end) and a female buckle member (the catch end). The male buckle member consists of a center guide rod forwardly extending from the front side with two spring arms equally spaced from the center rod. The two spring arms each have a retaining block that terminates at the front end. The female buckle member has a front open side and two side holes which hold and secure the two spring arms of the male buckle member.[21] This sort of buckle may be found on backpacks, belts, rifle slings, boots, and a host of other common but overlooked items. It is also known as the "parachute buckle".

Blimp buckle

The bottom part of the blimp, also known as a gondola, is called the buckle.

See also

References

- ↑ "Buckle".(2009). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 5.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pgs. 15 and 16.

- ↑ Hawkes, Sonia. (1974). "Some Recent Finds of Late Roman Buckles", Britannia, Vol. 5, pgs. 386, 387, 390, and 393. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Belt Buckle History" Archived January 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Buckle". (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 13

- 1 2 3 Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 7.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pgs. 5, 6, and 7.

- ↑ Ohio Travel Bag catalog 2011 (online 2012/13) and Weaver Leather catalog 2012

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pgs. 11 and 12.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 15.

- ↑ Hawkes, Sonia. (1974). "Some Recent Finds of Late Roman Buckles", Britannia, Vol. 5, pg. 386. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 32.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 41.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pgs. 43 and 44.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 44.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 45.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pg. 47.

- ↑ Meredith, Alan and Gillian. (2008). Buckles. Oxford: Shire Library. pgs. 8 and 9.

- ↑ Hsiao, Hsiung-Ming. US 7346965, issued 2008-03-25

External links

Media related to Buckles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Buckles at Wikimedia Commons