Brahma

| Brahma | |

|---|---|

| God of Creation | |

|

Brahma, the god who created Knowledge and the Universe[1] | |

| Devanagari | ब्रह्मा |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Brahma |

| Affiliation | Deva, Trimurti |

| Abode | Brahmapura (Satyaloka - Land of Truth) |

| Symbols | Vedas, Ladle, Utensil |

| Consorts | Sarasvati[2][3] |

| Mount | Haṃsa (swan/goose) |

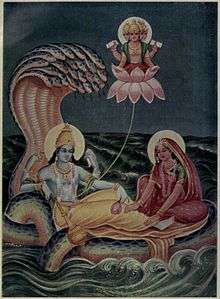

Brahma (/ˈbrəhmɑː/; Brahmā) is the creator god in the Trimurti of Hinduism. He has four faces, looking in the four directions.[1] Brahma is also known as Svayambhu (self-born),[4] Vāgīśa (Lord of Speech), and the creator of the four Vedas, one from each of his mouths.[1][5] Brahma is identified with the Vedic god Prajapati, as well as linked to Kama and Hiranyagarbha (the cosmic egg),[6][7] he is more prominently mentioned in the post-Vedic Hindu epics and the mythologies in the Puranas. In the epics, he is conflated with Purusha.[1] Brahma, along with Vishnu and Shiva, is part of a Hindu Trinity; however, ancient Hindu texts mention other trinities of gods or goddesses which do not include Brahma.[8][9][note 1]

While Brahma is often credited as the creator of the universe and various beings in it, several Puranas describe him being born from a lotus emerging from the navel of the god Vishnu. Other Puranas suggest that he is born from Shiva or his aspects,[11] or he is a supreme god in diverse versions of Hindu mythology.[6] Brahma, along with all deities, is sometimes viewed as a form (saguna) of the otherwise formless (nirguna) Brahman, the ultimate metaphysical reality and cosmic soul in Advaita philosophy.[9][7]

Brahma does not enjoy popular worship in present-age Hinduism and has lesser importance than the other members of the Trimurti, Vishnu and Shiva. Brahma is revered in ancient texts, yet rarely worshipped as a primary deity in India.[12] Very few temples dedicated to him exist in India; the most famous being the Brahma Temple, Pushkar in Rajasthan.[13] Brahma temples are found outside India, such as in Thailand at the Erawan Shrine in Bangkok.[14]

Etymology

The origins of Brahma are uncertain, in part because several related words such as one for Ultimate Reality (Brahman), and priest (Brahmin) are found in the Vedic literature. The existence of a distinct deity named Brahma is evidenced in late Vedic text.[15] A distinction between spiritual concept of Brahman, and deity Brahma, is that the former is gender neutral abstract metaphysical concept in Hinduism,[16] while the latter is one of the many masculine gods in Hindu mythology.[17] The spiritual concept of Brahman is far older, and some scholars suggest deity Brahma may have emerged as a personal conception and visible icon of the impersonal universal principle called Brahman.[15]

In Sanskrit grammar, the noun stem brahman forms two distinct nouns; one is a neuter noun bráhman, whose nominative singular form is brahma; this noun has a generalized and abstract meaning.[18]

Contrasted to the neuter noun is the masculine noun brahmán, whose nominative singular form is Brahma.[note 2] This noun is used to refer to a person, and as the proper name of a deity Brahma it is the subject matter of the present article.

History

Vedic literature

One of the earliest mention of Brahma with Vishnu and Shiva is in the fifth Prapathaka (lesson) of the Maitrayaniya Upanishad, probably composed in late 1st millennium BCE. Brahma is discussed in verse 5,1 also called the Kutsayana Hymn first, and expounded in verse 5,2.[19][20]

In the pantheistic Kutsayana Hymn,[19] the Upanishad asserts that one's Soul is Brahman, and this Ultimate Reality, Cosmic Universal or God is within each living being. It equates the Atman (Soul, Self) within to be Brahma and various alternate manifestations of Brahman, as follows, "Thou art Brahma, thou art Vishnu, thou art Rudra (Shiva), thou art Agni, Varuna, Vayu, Indra, thou art All."[19][21]

In verse 5,2 Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva are mapped into the theory of Guṇa, that is qualities, psyche and innate tendencies the text describes can be found in all living beings.[21][22] This chapter of the Maitri Upanishad asserts that the universe emerged from darkness (Tamas), first as passion characterized by action qua action (Rajas), which then refined and differentiated into purity and goodness (Sattva).[19][21] Of these three qualities, sattava is then mapped to Brahma, as follows:[23]

Now then, that part of him which belongs to Tamas, that, O students of sacred knowledge (Brahmacharins), is this Rudra.

That part of him which belongs to Rajas, that O students of sacred knowledge, is this Brahma.

That part of him which belongs to Sattva, that O students of sacred knowledge, is this Vishnu.

Verily, that One became threefold, became eightfold, elevenfold, twelvefold, into infinite fold.

This Being (neuter) entered all beings, he became the overlord of all beings.

That is the Atman (Soul, Self) within and without – yea, within and without !

While the Maitri Upanishad maps Brahma with one of the elements of Guṇa theory of Hinduism, the text does not depict him as one of the trifunctional elements of the Hindu Trimurti idea found in later Puranic literature.[24]

Post-Vedic, Epics and Puranas

The post-Vedic texts of Hinduism offer multiple theories of cosmogony, many involving Brahma. These include Sarga (primary creation of universe) and Visarga (secondary creation), ideas related to the Indian thought that there are two levels of reality, one primary that is unchanging (metaphysical) and other secondary that is always changing (empirical), and that all observed reality of the latter is in an endless repeating cycle of existence, that cosmos and life we experience is continually created, evolved, dissolved and then re-created.[25] The primary creator is extensively discussed in Vedic cosmogonies with Brahman or Purusha or Devi among the terms used for the primary creator,[25][26] while the Vedic and post-Vedic texts name different gods and goddesses as secondary creators (often Brahma in post-Vedic texts), and in some cases a different god or goddess is the secondary creator at the start of each cosmic cycle (kalpa, aeon).[11][25]

Brahma is a "secondary creator" as described in the Mahabharata and Puranas, and among the most studied and described.[27][28][29] Born from a lotus emerging from the navel of Vishnu, Brahma creates all the forms in the universe, but not the primordial universe itself.[30] In contrast, the Shiva-focussed Puranas describe Brahma and Vishnu to have been created by Ardhanarishvara, that is half Shiva and half Parvati; or alternatively, Brahma was born from Rudra, or Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma creating each other cyclically in different aeons (kalpa).[11] Thus in most Puranic texts, Brahma's creative activity depends on the presence and power of a higher god.[31]

In the Bhagavata Purana, Brahma is portrayed several times as the one who rises from the "Ocean of Causes".[32] Brahma, states this Purana, emerges at the moment when time and universe is born, inside a lotus rooted in the navel of Hari (deity Vishnu, whose praise is the primary focus in the Purana). The myth asserts that Brahma is drowsy, errs and is temporarily incompetent as he puts together the universe.[32] He then becomes aware of his confusion and drowsiness, meditates as an ascetic, then realizes Hari in his heart, sees the beginning and end of universe, and then his creative powers are revived. Brahma, states Bhagavata Purana, thereafter combines Prakriti (nature, matter) and Purusha (spirit, soul) to create a dazzling variety of living creatures, and tempest of casual nexus.[32] The Bhagavata Purana thus attributes the creation of Maya to Brahma, wherein he creates for the sake of creation, imbuing everything with both the good and the evil, the material and the spiritual, a beginning and an end.[33]

The Puranas describe Brahma as the deity creating time. They correlate human time to Brahma's time, such as a mahākalpa being a large cosmic period, correlating to one day and one night in Brahma's existence.[31]

The stories about Brahma in various Puranas are diverse and inconsistent. In Skanda Purana, for example, goddess Parvati is called the "mother of the universe", and she is credited with creating Brahma, gods and the three worlds. She is the one, states Skanda Purana, who combined the three Gunas - Sattva, Rajas and Tamas - into matter (Prakrti) to create the empirically observed world.[34]

The Vedic discussion of Brahma as a Rajas-quality god expands in the Puranic and Tantric literature. However, these texts state that his wife Saraswati has Sattva (quality of balance, harmony, goodness, purity, holistic, constructive, creative, positive, peaceful, virtuous), thus complementing Brahma's Rajas (quality of passion, activity, neither good nor bad and sometimes either, action qua action, individualizing, driven, dynamic).[35][36][37]

Iconography

Brahma is traditionally depicted with four faces and four arms.[38] Each face of his points to a cardinal direction. His hands hold no weapons, rather symbols of knowledge and creation. In one hand he holds the sacred texts of Vedas, in second he holds mala (rosary beads) symbolizing time, in third he holds a ladle symbolizing means to feed sacrificial fire, and in fourth a utensil with water symbolizing the means where all creation emanates from. His four mouths are credited with creating the four Vedas.[1] He is often depicted with a white beard, implying his sage like experience. He sits on lotus, dressed in white (or red, pink), with his vehicle (vahana) – hansa, a swan or goose – nearby.[38][39]

Chapter 51 of Manasara-Silpasastra, an ancient design manual in Sanskrit for making Murti and temples, states that Brahma statue should be golden in color.[40] The text recommends that the statue have four faces and four arms, have jata-mukuta-mandita (matted hair of an ascetic), and wear a diadem (crown).[40] Two of his hands should be in refuge granting and gift giving mudra, while he should be shown with kundika (water pot), akshamala (rosary), a small and a large sruk-sruva (laddles used in yajna ceremonies).[40] The text details the different proportions of the murti, describes the ornaments, and suggests that the idol wear chira (bark strip) as lower garment, and either be alone or be accompanied with goddesses Sarasvati on his right and Savitri on his left.[40]

Brahma's consort is the goddess Saraswati. She is considered to be "the embodiment of his power, the instrument of creation and the energy that drives his actions".[41]

Temples

India

Very few temples are primarily dedicated to Brahma and his worship in India.[12] One of the few and the most prominent Hindu temple for Brahma is the Brahma Temple, Pushkar.[13] Other temples include a temple in Asotra village in Balotra taluka of Rajasthan's Barmer district, which is known as Kheteshwar Brahmadham Tirtha.

Temples featuring Brahma also exist in Tirunavaya, the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, the Thripaya Trimurti Temple and Mithrananthapuram Trimurti Temple in Kerala. In Tamil Nadu, Brahma temples exist in the temple town of Kumbakonam, in Kodumudi and within the Brahmapureeswarar Temple in Tiruchirappalli.

There is a temple dedicated to Brahma in the temple town of Srikalahasti near Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh. A seven feet height of Chatrumukha (Four Faces) Brahma temple at Bangalore, Karnataka. In the coastal state of Goa, a shrine belonging to the fifth century, in the small and remote village of Carambolim in the Sattari Taluka in the northeast region of the state is found.

Famous murti of Brahma exists at Mangalwedha, 52 km from the Solapur district of Maharashtra and in Sopara near Mumbai. There is a 12th-century temple dedicated to him in Khedbrahma, Gujarat.

Other temples dedicated to Brahma

Middle: 12th-century Brahma with missing book and water pot, Cambodia;

Right: 9th-century Brahma in Prambanan temple, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

- Brahma Temple at Khokhan, in Kullu District, Himachal Pradesh

- Brahma Temple at Asotra, District Barmer, Rajasthan

- Brahma Temple at Oachira in Kollam district, Kerala

- Brahma temple at village aleo shrishty narayan, in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh

- Brahma Temple at Annamputhur village srinidheeswarar in Tindivanam,Tamil Nadu

- Brahma Temple at Pushkar , Rajasthan

- Thirunavaya, Thiruvallam , Kerala

- Brahma Temple at Royakotta road in Hosur , Tamil Nadu

- Uttamar Kovil in Srirangam, Tamil Nadu

- Kumbakonam, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu

- Khedbrahma, Gujarat

- The Brahma Temple near Panaji in the village of Brahma-Carambolim in the Satari taluka, Goa

- Bramhapureeswarar temple in Tirupattur, near Trichy, Tamil Nadu

- BrahmaKuti Temple at Brahmaavart (Bithoor), Kanpur (Uttar Pradesh)

- Brahma Temple at village Chhinch, Tehsil Bagidoa, District Banswara, Rajasthan

- Chaturmukha Brahma temple in Chebrolu, Andhra Pradesh

- As Part of Trimurti at Thripaya Trimurti Temple in Irinjalakuda, Thrissur in Kerala, India

- As Part of Trimurti at Mithrananthapuram Trimurti Temple in Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala, India

- Jagatpita Brahma in Ponmeri Shiva Temple in Vatakara in Kerala, India

Southeast Asia

The largest and most famous shrine to Brahma may be found in Cambodia's Angkor Wat. One of the three largest temples in the 9th-century Prambanan temples complex in Yogyakarta, central Java (Indonesia) is dedicated to Brahma, the other two to Shiva (largest of three) and Vishnu respectively.[42] The temple dedicated to Brahma is on southern side of Śiva temple.

A statue of Brahma is present at the Erawan Shrine in Bangkok, and continues to be revered in modern times.[14] The golden dome of the Government House of Thailand also contains a statue of Phra Phrom (Thai representation of Brahma). An early 18th-century painting at Wat Yai Suwannaram in Phetchaburi city of Thailand shows Brahma.[43]

The country name of Burma is derived from Brahma, and in medieval texts it is referred to as Brahma-desa.[44][45]

East Asia

Brahma is a popular deity in Chinese folk religion and there are numerous temples devoted to the god in China and Taiwan. Brahma is known in Chinese as Simianshen (四面神, "Four-Faced God"), Tshangs pa in Tibetan and Bonten in Japanese.[46]

Difference between Brahma, Brahman, Brahmin and Brahmanas

Brahman (Sanskrit: ब्रह्मन्, brahman)[47] is a metaphysical concept of Hinduism referring to the ultimate reality,[48] that, states Doniger, is uncreated, eternal, infinite, transcendent, the cause, the foundation, the source and the goal of all existence.[49] It is envisioned as either the cause or that which transforms itself into everything that exists in the universe as well as all beings, that which existed before the present universe and time, which exists as current universe and time, and that which will absorb and exist after the present universe and time ends.[49] It is a gender neutral abstract concept.[49][50][51]

Brahma (Sanskrit: ब्रह्मा, brahmā)[47] is distinct from Brahman.[48] Brahma is a male deity, in the post-Vedic Puranic literature,[52] who creates but neither preserves nor destroys anything. He is envisioned in some Hindu texts to have emerged from the metaphysical Brahman along with Vishnu (preserver), Shiva (destroyer), all other gods, goddesses, matter and other beings.[49] In theistic schools of Hinduism where deity Brahma is described as part of its cosmology, he is a mortal like all gods and goddesses, and dissolves into the abstract immortal Brahman when the universe ends, then a new cosmic cycle (kalpa) restarts again.[52][53] The deity Brahma is mentioned in the Vedas and the Upanishads but is uncommon,[54] while the abstract Brahman concept is predominant in these texts, particularly the Upanishads.[55] In the Puranic and the Epics literature, deity Brahma appears more often, but inconsistently. Some text suggest that god Vishnu created Brahma,[56] others suggest god Shiva created Brahma,[57] yet others suggest goddess Devi created Brahma,[58] and these texts then go on to state that Brahma is a secondary creator of the world working respectively on their behalf.[58][59] Further, the medieval era texts of these major theistic traditions of Hinduism assert that the saguna (representation with face and attributes)[60] Brahman is Vishnu,[61] Shiva,[62] or Devi[63] respectively, and that the Atman (soul, self) within every living being is same or part of this ultimate, eternal Brahman.[64]

Brahmin (Sanskrit: ब्राह्मण, Brahmin)[65] is a varna in Hinduism specialising in theory as priests, preservers and transmitters of sacred literature across generations.[66][67]

The Brahmanas, or Brahmana Granthas, (Sanskrit: ब्राह्मणग्रंथ, brāhmaṇa)[68] are one of the four ancient layers of texts within the Vedas. They are primarily a digest incorporating myths, legends, the explanation of Vedic rituals and in some cases philosophy.[69][70] They are embedded within each of the four Vedas, and form a part of the Hindu śruti literature.[71]

See also

- Brahma (Buddhism)

- Brahma Samhita

- Brahmastra

- Bonten (梵天)

- Creator deity

- Phra Phrom

- Brahma from Mirpur-Khas

- Brahmakumari

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The Trimurti idea of Hinduism, states Jan Gonda, "seems to have developed from ancient cosmological and ritualistic speculations about the triple character of an individual god, in the first place of Agni, whose births are three or threefold, and who is threefold light, has three bodies and three stations".[10] Other trinities, beyond the more common "Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva", mentioned in ancient and medieval Hindu texts include: "Indra, Vishnu, Brahmanaspati", "Agni, Indra, Surya", "Agni, Vayu, Aditya", "Mahalakshmi, Mahasarasvati, and Mahakali", and others.[8][9]

- ↑ In Devanagari brahma is written ब्रह्म. It differs from Brahma ब्रह्मा by having a matra (diacritical) in the form of an extra vertical stroke at the end. This indicates a longer vowel sound: long "ā" rather than short "a".

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce Sullivan (1999), Seer of the Fifth Veda: Kr̥ṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa in the Mahābhārata, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120816763, pages 85-86

- ↑ Elizabeth Dowling and W George Scarlett (2005), Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-0761928836 page 204

- ↑ David Kinsley (1988), Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520063392, pages 55-64

- ↑ Alf Hiltebeitel (1999), Rethinking India's Oral and Classical Epics, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226340517, page 292

- ↑ Barbara Holdrege (2012), Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438406954, pages 88-89

- 1 2 Charles Coulter and Patricia Turner (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge, ISBN 978-0786403172, page 258, Quote: "When Brahma is acknowledged as the supreme god, it was said that Kama sprang from his heart."

- 1 2 David Leeming (2009), Creation Myths of the World, 2nd Edition, ISBN 978-1598841749, page 146;

David Leeming (2005), The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195156690, page 54, Quote: "Especially in the Vedanta Hindu philosophy, Brahman is the Absolute. In the Upanishads, Brahman becomes the eternal first cause, present everywhere and nowhere, always and never. Brahman can be incarnated in Brahma, in Vishnu, in Shiva. To put it another way, everything that is, owes its existence to Brahman. In this sense, Hinduism is ultimately monotheistic or monistic, all gods being aspects of Brahman"; Also see pages 183-184, Quote: "Prajapati, himself the source of creator god Brahma – in a sense, a personification of Brahman (...) Moksha, the connection between the transcendental absolute Brahman and the inner absolute Atman." - 1 2 David White (2006), Kiss of the Yogini, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226894843, pages 4, 29

- 1 2 3 Jan Gonda (1969), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pages 212-226

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1969), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pages 218-219

- 1 2 3 Stella Kramrisch (1994), The Presence of Siva, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019307, pages 205-206

- 1 2 Brian Morris (2005), Religion and Anthropology: A Critical Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521852418, page 123

- 1 2 SS Charkravarti (2001), Hinduism, a Way of Life, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808997, page 15

- 1 2 Ellen London (2008), Thailand Condensed: 2,000 Years of History & Culture, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-9812615206, page 74

- 1 2 Bruce Sullivan (1999), Seer of the Fifth Veda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120816763, pages 82-83

- ↑ James Lochtefeld, Brahman, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798, page 122

- ↑ James Lochtefeld, Brahma, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798, page 119

- ↑ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 422–424

- ↑ Maitri Upanishad - Sanskrit Text with English Translation EB Cowell (Translator), Cambridge University, Bibliotheca Indica, page 255-256

- 1 2 3 4 Max Muller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 303-304

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1968), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Vol. 63, pages 215-219

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 344-346

- ↑ GM Bailey (1979), Trifunctional Elements in the Mythology of the Hindu Trimūrti, Numen, Vol. 26, Fasc. 2, pages 152-163

- 1 2 3 Tracy Pintchman (1994), The Rise of the Goddess in the Hindu Tradition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791421123, pages 122-138

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1969), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pages 213-214

- ↑ Bryant, ed. by Edwin F. (2007). Krishna : a sourcebook. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6.

- ↑ Sutton, Nicholas (2000). Religious doctrines in the Mahābhārata (1st ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 182. ISBN 81-208-1700-1.

- ↑ Asian Mythologies by Yves Bonnefoy & Wendy Doniger. Page 46

- ↑ Bryant, ed. by Edwin F. (2007). Krishna : a sourcebook. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6.

- 1 2 Frazier, Jessica (2011). The Continuum companion to Hindu studies. London: Continuum. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

- 1 2 3 Richard Anderson (1967), Hindu Myths in Mallarmé: Un Coup de Dés, Comparative Literature, Vol. 19, No. 1, pages 28-35

- ↑ Richard Anderson (1967), Hindu Myths in Mallarmé: Un Coup de Dés, Comparative Literature, Vol. 19, No. 1, page 31-33

- ↑ Nicholas Gier (1997), The Yogi and the Goddess, International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2, pages 279-280

- ↑ H Woodward (1989), The Lakṣmaṇa Temple, Khajuraho and Its Meanings, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 19, pages 30-34

- ↑ Alban Widgery (1930), The principles of Hindu Ethics, International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 40, No. 2, pages 234-237

- ↑ Joseph Alter (2004), Yoga in modern India, Princeton University Press, page 55

- 1 2 Kenneth Morgan (1996), The Religion of the Hindus, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120803879, page 74

- ↑ Philip Wilkinson and Neil Philip (2009), Mythology, Penguin, ISBN 978-0756642211, page 156

- 1 2 3 4 PK Acharya, A summary of the Mānsāra, a treatise on architecture and cognate subjects, PhD Thesis awarded by Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, published by BRILL, OCLC 898773783, page 50

- ↑ Charles Phillips et al (2011), Ancient India's Myths and Beliefs, World Mythologies Series, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-1448859900, page 95

- ↑ Trudy Ring et al (1996), International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania, Routledge, ISBN 978-1884964046, page 692

- ↑ Chami Jotisalikorn et al (2002), Classic Thai: Design, Interiors, Architecture., Tuttle, ISBN 978-9625938493, pages 164-165

- ↑ Arthur P. Phayre (2013), History of Burma, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415865920, pages 2-5

- ↑ Gustaaf Houtman (1999), Mental Culture in Burmese Crisis Politics, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, ISBN 978-4872977486, page 352

- ↑ Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- 1 2 Wendy Denier (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- 1 2 Helen K. Bond; Seth D. Kunin; Francesca Murphy (2003). Religious Studies and Theology: An Introduction. New York University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8147-9914-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Wendy Denier (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ↑ J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL Academic. p. 256. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

- ↑ Denise Cush; Catherine Robinson; Michael York (2012). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Routledge. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-1-135-18979-2.

- 1 2 R. M. Matthijs Cornelissen (2011). Foundations of Indian Psychology Volume 2: Practical Applications. Pearson. p. 40. ISBN 978-81-317-3085-0.

- ↑ Jeaneane D. Fowler (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-898723-93-6.

- ↑ Julius Lipner (1994). Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Routledge. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-415-05181-1.

- ↑ Edward Craig (1998). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Brahman to Derrida. Routledge. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-415-18707-7.

- ↑ S. M. Srinivasa Chari (1994). Vaiṣṇavism: Its Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Discipline. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 147. ISBN 978-81-208-1098-3.

- ↑ Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1981). Siva: The Erotic Ascetic. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-972793-3.

- 1 2 David Kinsley (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1992). The Presence of Siva. Princeton University Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 0-691-01930-4.

- ↑ Arvind Sharma (2000). Classical Hindu Thought: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-564441-8.

- ↑ Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 1335. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1992). The Presence of Siva. Princeton University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-691-01930-4.

- ↑ David Kinsley (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- ↑ William K. Mahony (1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. State University of New York Press. pp. 13–14, 187. ISBN 978-0-7914-3579-3.

- ↑ Monier Williams (1899), brahmin, Monier William's Sanskrit-English Dictionary, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Springfield, MA, USA: Merriam-Webster. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ↑ James Lochtefeld (2002), Brahmin, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0823931798, page 125

- ↑ H. W. Bodewitz (1990). The Jyotiṣṭoma Ritual: Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa. BRILL Academic. ISBN 90-04-09120-3.

- ↑ Brahmana Encyclopædia Britannica (2013)

- ↑ Klaus Klostermaier (1994), A Survey of Hinduism, Second Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791421093, pages 67-69

- ↑ "Brahmana". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brahma. |

- Brahma at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Hinduism - Brahma And The Trimurti

- Hindu Brahma in Thai Literature - Maneepin Phromsuthirak