Mongo people

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (12 million) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| Languages | |

| Mongo, Lingala | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, African Traditional Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Bantu peoples |

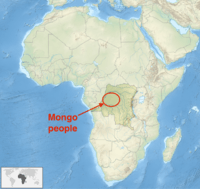

The Mongo people are a Bantu ethnic group who live in the equatorial forest of Central Africa.[1] They are the second largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, highly influential in its north region.[2] A diverse collection of sub-ethnic groups, they are mostly residents of a region north of the Kasai and the Sankuru Rivers, south of the main Congo River bend.[1] Their highest presence is in the province of Équateur and the northern parts of the Bandundu Province.[3]

| Mongo | |

|---|---|

| People | Bomongo |

| Language | Lomongo, Nkundo |

.jpg)

The Mongo people, despite their diversity, share a common legend wherein they believe that they are the descendants of a single ancestor named Mongo.[4] They also share similarities in their language and social organization, but also have differences. Anthropologists first proposed the Mongo unity as an ethnic group in 1938 particularly by Boelaert, followed by a major corpus on Mongo people in 1944 by Vanderkerken – then the governor of Équateur.[4]

The Mongo people traditionally speak the Mongo language (also called Nkundo) or one of the related languages in the Bantu Mongo family, in the Niger-Congo family of languages.[1] The Lingala language, however, often replaces Mongo in urban centers. This language has about 200 dialects, and these are found clustered regionally as well as based on Mongo sub-ethnic groups such as Bolia, Bokote, Bongandu, Ekonda, Iyaelima, Konda, Mbole, Mpama, Nkutu, Ntomba, Sengele, Songomeno, Dengese and Tetela-Kusu, Bakutu, Boyela and many others.[5][6][7]

History

The historic roots of the Mongo people are unclear, but they probably settled along the rainy, hot and humid river valleys of northern and western Congo in early centuries of the 1st millennium.[8] Farming of staples such as yam and banana was likely established by about 1000 CE.[8] The Belgian colonial rule impacted the traditions, culture and religious beliefs of the Mongo people, and they predominantly converted to one of numerous denominations of Christianity found in Congo.[8][9] The influence of Islamic missionary activity from northern Africa has been a source of deep resentment for the Christian Mongo people, leading to a history of conflicts between them and some Muslim ethnic groups found in the neighboring northeastern regions of Congo.[9]

According to Alexander Reid, the Mongo people suffered during the active slave capture, trade and export in the 18th and 19th centuries, where "thousands of Mongo people as captured slaves passed through the Zanzibar route by the Arabs".[10] A system of enslavement and slave trade led by Arab incursions, state Patrick Harries and David Maxwell, existed and impacted the Mongo people before the colonial period.[11] The arrival of Belgium as a colonial ruler, with its Leupoldian exploitation model, combined with imported diseases such as sleeping sickness and syphilis, decimated the Mongo people over the colonial history.[11] The colonial period also brought an ecological and economic change from the introduction of cocoa, coffee, rubber plantations as well as trapping of animals as pets and for zoos.[11]

Society and culture

Given the equatorial forests they live in, like neighboring ethnic groups, the Mongo people cultivate cassava, yam and banana as staple foods. This is supplemented with wild-plant and edible-insects gathering, seasonal vegetables and beans, fishing, and hunting.[8] The society is patrilineal, and traditionally based on a joint family household called Etuka with twenty to forty members, derived from an ancestor lineage.[8] The male elder of the Etuka is called Tata (meaning father). A cluster of Etuka form a village of the Mongo people.[8] Disputes and covenants between lineages were typically resolved through goods or inter-marriages. Some sub-ethnic groups found in the southern parts of Congo have had a chief, instead of being a collection of lineages,[1] with the chief known as Bokulaka.[8]

Traditional religion of the Mongo people is largely one of ancestor worship, belief in nature spirits, fertility rites, with shamanic practices such as magic, sorcery, and witchcraft. Mongo artistic achievements, songs, musical instruments and carvings show richness and high sophistication. Like many ancient cultures, the Mongo people have used the oral tradition to preserve and transmit knowledge to the next.[1] Polygamy has been a part of the Mongo culture into the modern age, though missionaries have attempted to curb this part after their conversion to Christianity.[8]

The musician Jupiter Bokondji is of Mongo descent.[12]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mongo people. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mongo people, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Kevin Shillington (2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. p. 738. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

- ↑ Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.

- 1 2 Crawford Young (2015). Politics in Congo: Decolonization and Independence. Princeton University Press. pp. 247–249. ISBN 978-1-4008-7857-4.

- ↑ Mongo-Nkundu, A language of Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethnologue

- ↑ An Crúbadán - Corpus Building for Minority Languages, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, USA

- ↑ Rita Milios (2014). Democratic Republic of Congo. Simon Schuster. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4222-9435-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ronald Johnson (1996). "Mongo people". In David Levinson. Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 9. The Gale Group. OCLC 22492614.

- 1 2 René Lemarchand (1964). Political Awakening in the Belgian Congo. University of California Press. pp. 122–133. GGKEY:TQ2J84FWCXN.

- ↑ Alexander James Reid (1979). The roots of Lomomba: Mongo Land. Exposition Press, University of California Archives. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-682-49008-5.

- 1 2 3 Patrick Harries; David Maxwell (2012). The Spiritual in the Secular: Missionaries and Knowledge about Africa. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 168–171. ISBN 978-1-4674-3585-7.

- ↑ "Cargo". Archived from the original on December 20, 2014.