Biscayan dialect

| Biscayan | |

|---|---|

| Western Dialect | |

| Bizkaiera | |

| Pronunciation | /biskɑːiɑːn/ |

| Native to | Spain |

| Region | Biscay, into Álava and Gipuzkoa |

Native speakers | 247.000 (2001) |

|

Basque

| |

| Dialects | Western, Eastern, Alavese (extinct) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog |

bisc1236 (Biscayan)[1]aval1237 (Alavan)[2] |

|

Biscayan | |

Biscayan, sometimes Bizkaian (Basque: Bizkaiera, Spanish: Vizcaino)[3] is a dialect of the Basque language spoken mainly in Biscay, one of the provinces of the Basque Country of Spain.

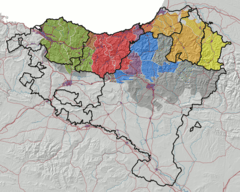

It is named as Western in the Basque dialects' classification drawn up by linguist Koldo Zuazo,[4] since it is not only spoken in Biscay but also extends slightly into the Northern fringes of Alava and deeper in the Western part of Gipuzkoa. The dialect's territory bears great similarity to that of the Caristii tribe, as described by Roman authors.

While it is treated as stylish to write in Biscayan and the dialect is still spoken generally in about half of Biscay and some other municipalities, it suffers from the double pressure of Unified Basque and Spanish.

Biscayan was used by Sabino Arana and its early Basque nationalist followers as one of the signs of Basqueness.

Sociolinguistic Features

In the words of Georges Lacombe, because of the special features of this dialect, Euskera could well be divided into two groups of dialects: Biscayan and the rest. He argued that this dialect was so different from the rest, that the isoglosses separating it from the adjacent dialects (Gipuzkoan or central) are so close to each other that form a clear line; that is, the phonetic-phonological, morphosyntactic and lexical features of Biscayan coincide geographically to the point of creating a distinctively clear and defined dialectical border.

Because of these differences both with the rest of the Basque dialects and also with Standard Basque, and respecting their corresponding uses, the Euskaltzaindia has produced a Model for Written Biscayan (in Basque: Bizkaieraren idatzizko ereduaren finkapenak), a set of rules mainly focused on morphosyntax. The official use of the dialects of Euskera is regulated through Regulation 137 of the Euskaltzaindia, according to which the use of Batua should be limited to the fields of communication, administration and teaching.

Since 1997 and according to the new dialectical classification realized by Koldo Zuazo, author of "Euskalkiak. Herriaren lekukoak" (Elkar, 2004), the name given to Biscayan is the Western Dialect, due to its use not being limited to the province of Biscay, but with users in some Gipuzkoan regions such as Debagoiena (mainly) and Debabarrena, and also some Alavan municipalities such as Aramaio (Aramayona) and Legutio (Villarreal).

According to study by Yrizar, this dialect was spoken in the seventies by around 200,000 people,[5] with the number of estimated speakers approaching 300,000 by the eighties. In 1991 16% of the population if this province could speak Basque, and data gathered in 2001 data 22% of the total 1.122.710 Biscayans (i.e. 247,000) could speak and write in Basque. However, this data is only illustrative, as there is no record of how many of the Basque speakers spoke Biscayan specifically and it does not take into account Biscayan speakers in Gipuzkoan territory (Bergara, Leintz Gatzaga, Mondragon, Oñati, etc.)

Subdialects and Variations

_02.jpg)

Biscayan is not a homogeneous dialect, it has two subdialects and eight main variations.[6]

Western Subdialect

- Uribe-Kosta

- Mungialdea

- Txorierri

- Nerbion Valley

- Zeberio

- Arratia

- Orozko

Variations

- Dialectal variation around the border between the Western and Eastern subdialects. The territory includes: Busturialdea, Otxandio and Villarreal.

- Dialectal variation happens the border between the Western dialect (Biscayan) and the Central dialect (Gipuzkoan). The territory includes: Elgoibar, Deba, Mendaro and Mutriku.

Eastern Subdialect

Geography and History

The borders of Biscayan match those of the pre-roman tribe of the Caristii, which is probably not a coincidence. Biscay was formerly included, along with Alava and the Valley of Amezcoa, within the ecclesiastical circumscription of Calahorra, which explains the wide influence of Biscayan (or Western Dialect) in the language of these regions. This does not mean Alavan dialect (nowadays extinct) would have had the same features as the Biscayan, but rather some common characteristics with a personality of its own.

Phonology

Some features of Biscayan as perceived by other dialect speakers may be summed up as follows:

- The verb root "eutsi" used for the dative auxiliary verb (NOR-NORI-NORK), e.g. "dosku"/"deusku" vs. "digu".

- Auxiliary verb forms "dot - dok - dozu" most of the times, as opposed to general Basque "dut".

- Convergence of sibilants: z /s̻/, x /ʃ/ and s /s̺/ > x/ʃ/; tz /ts̻/, tx /tʃ/ and ts /ts̺/ > tz /ts̻/.

- Clusters -itz generally turned into -tx, e.g. "gaitza" > "gatxa".

- The conspicuous absence of past tense 3rd person mark z- at the beginning of auxiliary verbs, e.g. "eban" vs. "zuen".

- Assimilation in vowel clusters at the end of the noun phrase, notably -ea > -ie/i and -oa > -ue/u.

- v-Ñ-v ending words, as opposed to the Beterri Gipuzkoan v-Y-v: konstituziño vs konstituziyo, standard Basque konstituzio.

- In spelling, it has no h and it has -iñ- and -ill- where standard Basque has -in- and -il-.

Vocabulary

Biscayan dialect has a very rich lexicon, with vocabulary varying from region to region, and from town to town. For example while gura (to want) and txarto (bad) are two words widely used in Biscayan, some Biscayan speaker might use nahi (for to want) and gaizki (for bad), which are generally used in other dialects.[7] One of the current main experts in local vocabulary is Iñaki Gaminde, who in the last years has extensively researched and published on this subject.

|

|

|

Media

Radio

- Bizkaia Irratia: FM 96.7

- Arrakala Irratia: FM 106 (Lekeitio).

- Arrate Irratia: FM 87.7 (Eibar).

- Irratia Arrasate irratia: FM 107.7 (Debagoiena).

- Bilbo Hiria Irratia: FM 96.0 (Bilbao).

- Itsuki Irratia: FM 107.3 (Bermeo).

- Matrallako Irratixa: FM 102.8 (Eibar).

- Radixu Irratia: FM 105.5 (Ondarroa).

- Tas-Tas: FM 95 (Bilbao).

Newspaper

- Goiena: Debagoiena

Magazine

- Aikor: Txorierri.

- Anboto: Durangaldea.

- Bagabiz Aldizkaria: Gernika.

- Barren: Elgoibar.

- Begitu: Arratia.

- Berton: Bilbao.

- Bizkaie: Txurdinaga, Bilbao.

- Drogetenitturri: Ermua.

- Eta kitto!: Eibar.

- Kalaputxi: Mutriku.

- Pil-pilean: Soraluze.

- Prest!: Deusto, Bilbao.

Television

- GOITB: Debagoiena.

- Urdaibai Telebista: Gernika.

See also

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Biscayan". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Alavan". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Or in the unified form of this same dialect, Bizkaiko euskerea; other used names are euskera, euzkera, euskala, euskiera, uskera, according to the General Basque Dictionary.

- ↑ Zuazo, Koldo. "Clasificación actual de los dialectos". hiru.eus. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "El Dialecto Bizkaino". hiru.eus. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

En el estudio llevado a cabo por Yrizar en 1970, el bizkaino era hablado por unos 200.000 hablantes.

- ↑ Zuazo, Koldo (2015). "Euskalkiak - Ezaugarriak". euskalkiak.eus. University of the Basque Country. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Amuriza, Xabier. "Bizkaierazko gitxieneko hiztegia - "Vocabulario básico del vizcaíno" (PDF). mendebalde.com. Bizkaiko Foru Aldundia. Retrieved 10 June 2016.