Beaverkill Bridge

| Beaverkill Bridge | |

|---|---|

Bridge from east side of stream, 2008 | |

| Coordinates | 41°58′53.6″N 74°50′10.2″W / 41.981556°N 74.836167°WCoordinates: 41°58′53.6″N 74°50′10.2″W / 41.981556°N 74.836167°W |

| Carries |

|

| Crosses | Beaver Kill |

| Locale | Beaverkill, NY, USA |

| Other name(s) | Conklin Bridge |

| Maintained by | Town of Rockland |

| Heritage status | NRHP# 07001038[1] |

| ID number | 000000003357260[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Covered lattice truss bridge |

| Total length | 98 feet (30 m)[3] |

| Width | 13 feet (4.0 m)[3] |

| Height | 11 1⁄2 feet (3.5 m)[3] |

| Load limit | 3 tons (2.7 tonnes) |

| Clearance above | 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m) |

| History | |

| Construction end | 1865 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 80[2] |

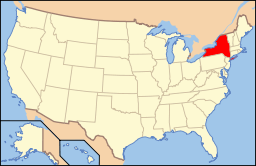

Beaverkill Bridge, also known as Conklin Bridge, is a wooden covered bridge over the Beaver Kill north of the hamlet of Roscoe in the Town of Rockland, New York, United States, that carries Conklin Road through Beaverkill State Campground. It was erected in 1865, one of the first bridges over the river in what was then still a largely unsettled region of the Catskill Mountains.

It uses an unusual modification of the lattice truss design perfected earlier in the 19th century by Ithiel Town. There is some dispute over which of three men claimed as its builder actually did; it is likely that all of them had some role. It is one of the 29 historic covered bridges in New York State. After undergoing some repairs over the course of the late 20th century, in 2007 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the northernmost property listed in Sullivan County and the only one of four covered bridges in it to be listed. Repair and maintenance efforts continue.

Structure

The bridge is located along Campsite Road (County Route 30) in an area with the public campground, one of the oldest in the Catskill Park, on both sides of the river. It goes almost due east-west across a south-flowing stretch of the Beaver Kill's generally east-southeast flow at this point, nearly 1,800 feet (550 m) above sea level. The entire area is heavily forested and minimally developed. The road curves from the Cragie Clair Road junction to the south and ends at Berry Brook Road just across the bridge, a short distance south of the Delaware County line.[3]

It is a 98-foot (30 m) hemlock lattice truss bridge supported by dry-laid fieldstone abutments faced in concrete at either end. On the east a ten-foot (3 m) approach ramp supported by a steel I-beam[4] leads up slightly to the portal past a rustic wooden fence along either side of the road that becomes timber guide rails. A plank deck 13 feet (4.0 m) wide is supported by eight irregularly spaced stringers atop 8-by-14-inch (20 by 36 cm) wood planks. Four of the cross beams extend beyond the bridge where they connect to the upper chord via sway braces. On either side vertical board-and-batten siding begins a foot below the lower chord and rises to a gabled metal roof, 11 1⁄2 feet (3.5 m) high, supported by tie-beam rafters with transverse metal rods and diagonal cross-bracing.[4] Interior clearance is only 6 1⁄2 feet (2.0 m), enforced by metal height restrictors near the portals.[3]

Two sets of heavy 3-by-12-inch (7.6 by 30.5 cm) timber planks serve as the top and bottom chords, with a secondary lower chord at deck level. Twelve-inch (30 cm) diagonals, fastened at each intersection by two-inch (5 cm) treenails, radiate out from the middle to either end.[4] They are supplemented by additional diagonals at the ends and four wooden buttresses along the exterior on either side.[3]

History

The bridge was an early step in bringing civilization to a remote area that had remained mostly unsettled well into the 19th century. It remained long after the small town that grew around it went into decline. In the mid-20th century a proposal to replace it aroused community opposition, and it has received extensive repairs since then.

1865–1880s: Core of a tannery town

For much of the early 19th century northern Sullivan County remained largely unsettled, partly due to ongoing land title disputes from the Hardenburgh Patent and partly due to its ruggedness and shortage of arable land. Only loggers, hunters and trappers ventured into the remote valley of the Beaverkill above its confluence with Willowemoc Creek via an 1815 road. A tannery was established near the bridge site in 1832, processing the bark of the abundant Eastern Hemlock trees in the region into tannin for the leather industry. The small hamlet of Beaverkill grew up around it, and several other tanneries followed.[3]

That remained the only settlement in the area for some time. In 1859 the Town of Rockland was still described as "a rough, wild region". Seven years after the bridge was built in 1865, it had a population of roughly a hundred, a school and a post office.[3] A bridge probably existed, though no record has been found.[5]

The bridge has long been attributed locally to John Davidson, a Scottish immigrant whose father had settled the family in Downsville to the north to raise sheep. After his marriage, Davidson moved to Shin Creek (today Lew Beach) where he farmed, logged and owned a sawmill while raising a family of 14. One of the younger children, J.D. Davidson, said in a letter late in his own life, in 1942, that his father had built the bridge, along with two other covered bridges in the town over the Willowemoc, only one of which (Van Tran Flat) is extant.[3]

In the 1970s, descendants of Davidson's younger brother Thomas claimed it was he who had built the bridge. An 1895 Delaware County biographical review further credits James Coulter of Bovina with the Beaverkill bridge as well as several others. Coulter's biography says, he had moved from bridge building to general carpentry by 1859, before the bridge's construction date. He was, however, still alive at the time the biographical review was published and could have served as a source for it.[3]

It is likely that all three worked on the bridge. Coulter was also the son of Scottish immigrants to the area and likely acquainted with the Davidsons. On a large public project it is also likely that several local people with the requisite expertise were involved to some degree.[3][5]

The bridge's design is the lattice truss patented earlier in the century by Ithiel Town in 1820. Its distinctive feature is the diagonals connected to the lower chord by pins, which eliminated the need for vertical members on longer bridges. It remained popular through the American Civil War, making the Beaverkill bridge one of the last of its kind.[3]

A major deviation from Town's design are the additional diagonals at the ends, which distribute the load over a smaller area and eliminates the need for long abutment seats of bolster beams. A patent was granted in 1863 for a similar variation on Town's design, so it is quite likely that this technique was not developed by the builder of the Beaverkill bridge. It is, however, unusual for New York. Davidson's three are the only ones known to have been built in the state.[3]

1880s–present: Restored community icon

The bridge is first shown on local maps in 1875. After the 1880s, the combination of depleted hemlock stands and a synthetic process for making tannin led to the demise of that industry along the upper Beaverkill. It was replaced by seasonal visitors who came to appreciate the scenic beauty of the area, now with some landholdings part of the state's recently created Forest Preserve and thus kept "forever wild", and its recreational offerings, particularly dry-fly fishing for trout in the upper Beaver Kill. Railroads, and later automobiles, made the valley more accessible than it had been to previous generations of anglers, and litter and other overuse problems began developing along those stretches of the river accessible to the public.[3]

In response, during the 1920s the state began constructing areas where those anglers could camp. While the hamlet of Beaverkill had dwindled to almost a ghost town, it was the site of a trout pool popular with anglers,[6] and thus the area on both sides of the bridge was turned into the second public campground in the Catskill Park after North-South Lake. Its facilities were further refined by Civilian Conservation Corps workers in the late 1930s; it became the prototype for other state-owned campgrounds in and outside of the Catskills.[3]

The town proposed to replace it with a more modern metal bridge in 1948. It abandoned the plan in response to preservation efforts led by a local citizen. Instead of demolishing it, the town board spent $700 (equivalent to $7,000 in 2015)[7] to restore it, although it is not known what work was done. As part of the preservation, ownership of the bridge was transferred to the county. Over the next several decades, it made repairs and replacements as needed, including facing the abutments in concrete, the only significant change in the bridge's appearance since its construction.[3]

In the late 1990s, the bridge was surveyed and inventoried for the Historic American Engineering Record. At that time, the county opposed listing it on the National Register since its Department of Public Works felt that could hamper their efforts to assure its safety. The local bridge committee also feared that designating it as a historic structure would increase the costs of running the bridge in a way that could not be offset by the grants available. The height restrictors and load limit were imposed at the end of the 20th century.[8]

Along with a century-old iron bridge nearby, the Beaverkill Bridge is the only crossing into the rest of the town and county for the residents on the river's north side. Both are regarded as structurally deficient for modern needs[2] and have reduced load limits that may preclude their use by heavier service and emergency vehicles.[9] In 2000 the state studied what it could do to address that problem.[10] Eight years later the bridge was closed for repairs, requiring a three-mile (5 km) detour via Craigie Claire Road.[11] A $72,000 federal grant the following year, 2009, was meant for further repairs.[12]

See also

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York

- List of bridges on the National Register of Historic Places in New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sullivan County, New York

References

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places listings 10/12/2007". National Park Service. October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Bridge #000000003357260". National Bridge Inventory at nationalbridges.com. 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 LaFrank, Kathleen (January 2007). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Beaverkill Bridge". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Bennett, Lola (February 2003). "Beaverkill Bridge, Spanning Beaver Kill, TR 30 (Craigie Claire Road), Roscoe vicinity, Sullivan County, NY". Historic American Engineering Record. Library of Congress. p. 3. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- 1 2 Bennett, 4.

- ↑ Bennett, 5.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ Bennett, 2 and 5.

- ↑ Scott, Brendan (April 29, 2001). "Modern times may spell doom for less-historic Beaverkill bridge". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ↑ Bosch, Adam (April 25, 2000). "State moves to preserve bridges". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Beaverkill Covered Bridge now closed for repairs". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. April 21, 2008. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ↑ Bosch, Adam (January 9, 2009). "Sullivan County bridge gets $72,000 makeover". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beaverkill Covered Bridge. |

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-329, "Beaverkill Bridge", 10 photos, 11 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- Beaverkill / Conklin Bridge, at New York State Covered Bridge Society

- Beaverkill or Conklin Bridge, at Covered Bridges of the Northeast USA