Battle of Naissus

| Battle of Naissus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman-Gothic Wars of the 3rd century AD Part of the Roman-Germanic wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gallienus or Claudius II | unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Naissus (268 or 269 AD) was the defeat of a Gothic coalition by the Roman Empire under Emperor Gallienus (or Claudius II) near Naissus (Niš in present-day Serbia). The events around the invasion and the battle are an important part of the history of the Crisis of the Third Century.

The result was a great Roman victory which, combined with the effective pursuit of the invaders in the aftermath of the battle and the energetic efforts of the Emperor Aurelian, largely removed the threat from Germanic tribes in the Balkan frontier for the following decades.

Sources

As is often the case in the history of the Roman Empire in the troubled 3rd century, it is very difficult to reconstruct the course of events around the battle of Naissus. Surviving accounts of the period, including Zosimus' New History, Zonaras' Epitome of the Histories, George Syncellus' Selection of Chronography, and the Augustan History, rely principally on the lost history of the Athenian Dexippus. The text of Dexippus has survived only indirectly, through quotations in the fourth-century Augustan History and extracts in ninth-century Byzantine compilations.[1] Despite his importance for the period, Dexippus has been declared a "poor" source by the modern historian David S. Potter.[2] To make matters worse, the works making use of Dexippus (and likely another unknown contemporary source) provide an almost radically different interpretation of events.[3] The imperial propaganda in the age of Constantine's dynasty added more confusion by attributing all the calamities to the reign of Gallienus to avoid blemishing the memory of Claudius (supposed ancestor of the dynasty).[4]

As a consequence, controversy still exists on the number of invasions and the order of events and on which reign those events must be attributed.[5] Therefore, there is a dispute over who was the Emperor and head of the army at the time of the battle. In 1939, Andreas Alföldi, preferring the single invasion theory, suggested that Gallienus was the only one responsible for defeating the barbarian invasions, including the victory at Naissus.[6] His view had been broadly accepted since then, but modern scholarship usually attributes the final victory to Claudius II.[7] The single invasion theory has been also rejected in favour of the two separate invasions. The narrative below follows the latter view but the reader must be warned that the evidence is too confused for an entirely safe reconstruction.[8]

Background

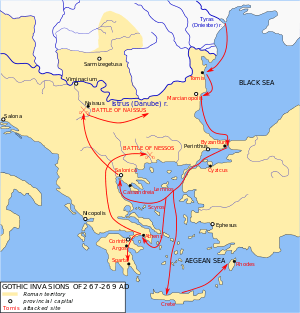

The battle of Naissus came about as a result of two massive invasions of "Scythian" tribes (as our sources[9] anachronistically call them) into Roman territory between 267 and 269. The first wave came during the reign of Gallienus in 267 and started when the Heruli, raiding on 500 ships,[10] ravaged the southern Black Sea coast and unsuccessfully attacked Byzantium and Cyzicus. They were defeated by the Roman navy but managed to escape into the Aegean Sea, where they ravaged the islands of Lemnos and Skyros and sacked several cities of the southern Greece province of Achaea, including Athens, Corinth, Argos, and Sparta. Then an Athenian militia, led by the historian Dexippus, pushed the invaders to the north where they were intercepted by the Roman army under Gallienus.[11] He won an important victory near the Nestos River, on the boundary between Macedonia and Thrace, with the aid of the Dalmatian cavalry. Reported barbarian casualties were 3,000 men.[12] Subsequently, the Heruli leader Naulobatus came to terms with the Romans.[10]

In the past, the battle on the Nessos was identified as the Battle of Naissus, but modern scholarship has rejected this view. On the contrary, there is a theory that the victory at Nessos was so decisive that Claudius' efforts against the Goths (including the battle of Naissus) were no more than a mopping-up operation.[13] After his victory, Gallienus left Marcian in place and hastily left for Italy, intending to suppress the revolt of his cavalry officer Aureolus.[14] After Gallienus was assassinated outside Milan in the summer of 268 in a plot led by high officers in his army, Claudius was proclaimed emperor and headed to Rome to establish his rule. Claudius' immediate concerns were with the Alemanni, who had invaded Raetia and Italy. After he defeated them in the Battle of Lake Benacus, he was finally able to take care of the invasions in the Balkan provinces.[15]

In the meantime, the second and larger sea-borne invasion had started. An enormous coalition of "Scythians"—actually consisting of Goths (Greuthungi and Thervingi), Gepids and Peucini, led again by the Heruli—assembled at the mouth of river Tyras (Dniester).[16] The Augustan History and Zosimus claim a total number of 2,000–6,000 ships and 325,000 men.[17] This is probably a gross exaggeration but remains indicative of the scale of the invasion. After failing to storm some towns on the coasts of the western Black Sea and the Danube (Tomi, Marcianopolis), the invaders attacked Byzantium and Chrysopolis. Part of their fleet was wrecked, either because of Gothic inexperience in sailing through the violent currents of the Propontis[18] or because it was defeated by the Roman navy. They then entered the Aegean Sea and a detachment ravaged the Aegean islands as far as Crete and Rhodes. While their main force had constructed siege works and was close to taking the cities of Thessalonica and Cassandreia, it retreated to the Balkan interior at the news that the emperor was advancing. On their way, they plundered Doberus (Paionia ?) and Pelagonia.

The battle

The Goths were engaged near Naissus by a Roman army advancing from the north. The battle most likely took place in 269, and was fiercely contested. Large numbers on both sides were killed but, at the critical point, the Romans tricked the Goths into an ambush by pretended flight. Some 50,000 Goths were allegedly killed or taken captive.[12] It seems that Aurelian, who was in charge of all Roman cavalry during reign of Claudius, led the decisive attack in the battle.

Aftermath

A large number of Goths managed to escape towards Macedonia, initially defending themselves behind their laager. Soon, many of them and their pack animals, distressed as they were by the harassment of the Roman cavalry and the lack of provisions, died of hunger. The Roman army methodically pursued and surrounded the survivors at Mount Haemus where an epidemic affected the entrapped Goths.[19] After a bloody but inconclusive battle, they escaped but were pursued again until they surrendered. Prisoners were admitted to the army or given land to cultivate and become coloni. The members of the pirate fleet, after the failed attacks on Crete and Rhodes, retreated and many of them suffered a similar end.[20] However the plague also affected the pursuing Romans and emperor Claudius, who died from it in 270.[21]

The psychological impact of this victory was so strong that Claudius became known to posterity as Claudius II Gothicus Maximus ("conqueror of the Goths"). However devastating the defeat, the battle did not entirely break the military strength of the Gothic tribes.[22] Besides, the troubles with Zenobia in the East and the breakaway Gallic Empire in the West were so urgent that the victory at Naissus could only serve as a temporary relief for the troubled Empire. In 271, after Aurelian repelled another Gothic invasion, he abandoned the province of Dacia north of the Danube in order to rationalize the defense of the Empire.[23]

Citations

- ↑ David S. Potter, p.232–233

- ↑ David S. Potter, p.232–234

- ↑ John Bray, p.283, David S. Potter, p.641–642, n.4.

- ↑ David S. Potter, p.266

- ↑ John Bray, p.279. Also David S. Potter, p.263

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History, vol 12, chapter 6, p.165–231, Cambridge University Press, 1939

- ↑ John Bray, p.284–285, Pat Southern, p.109. Also see Alaric Watson, p.215, David S. Potter, p.266, H. Wolfram, p.54

- ↑ John Bray, p.286–288, Alaric Watson, p.216

- ↑ Zosimus, see also George Syncellus, p.716

- 1 2 G. Syncellus, p.717

- ↑ Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Gallienii, 13.8

- 1 2 Zosimus, 1.43

- ↑ T. Forgiarini, A propos de Claude II: Les invasion gothiques de 269–270 et le role de l' empereur, in Les empereurs illyriens, Frezouls et Jouffroy, p.81–86. (as cited in D. Potter, p.642). This view is in agreement with A. Alfoldi

- ↑ Zosimus, 1.40

- ↑ John Bray, p.290

- ↑ The Historia Augusta mentions Scythians, Greuthungi, Tervingi, Gepids, Peucini, Celts and Heruli. Zosimus names Scythians, Heruli, Peucini and Goths.

- ↑ Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Divi Claudii, 6.4

- ↑ Zosimus, 1.42

- ↑ Zosimus, 1.45

- ↑ John Bray, p.282. See Zosimus, 1.46

- ↑ G. Syncellus, p.720

- ↑ Alaric Watson, p.216

- ↑ David S. Potter, p.270

References

Primary sources

- Zosimus, Historia Nova (Ancient Greek: Νέα Ἱστορία), book 1, in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae, ed. Bekker, Weber, Bonn, 1837

- George Syncellus, Chronographia (Ancient Greek: Ἐκλογὴ χρονογραφίας), in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae, ed. Dindorf, Bonn, 1829

- Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Gallieni Duo & Vita Divi Claudii, Loeb Classical Library, 1921–1932 (English translation), on-line at Lacus Curtius

- Zonaras, Epitome historiarum (Ancient Greek: Ἐπιτομὴ ἱστοριῶν), book 12, in Patrologia Graeca, ed. J.P.Migne, Paris, 1864, vol 134

Secondary sources

- Bray, John. Gallienus: A Study in Reformist and Sexual Politics, Wakefield Press, 1997. ISBN 1-86254-337-2

- Potter, David S. The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395, Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-10058-5

- Southern, Pat. The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0-415-23943-5

- Watson, Alaric. Aurelian and the Third Century, Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0-415-30187-4

- Wolfram, Herwig. History of the Goths (transl. by Thomas J. Dunlap), University of California Press, 1988. ISBN 0-520-06983-8

Coordinates: 43°18′N 21°54′E / 43.3°N 21.9°E