Battle of Kampar

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Kampar (30 December 1941 – 2 January 1942) was an engagement of the Malayan Campaign during World War II, involving British and Indian troops from the 11th Indian Infantry Division and the Japanese 5th Division.

On 27 December, in an effort to prevent the capture of RAF Kuala Lumpur, the 11th Indian Infantry Division occupied Kampar, which offered a strong natural defensive position. In doing so they were also tasked with delaying the advancing Japanese troops long enough to allow the 9th Indian Infantry Division to withdraw from the east coast. The Japanese intended to capture Kampar as a New Year’s gift to Emperor Hirohito and on 30 December the Japanese began surrounding the British and Indian positions. The following day fighting commenced. The Allied forces were able to hold on for four days before withdrawing on 2 January 1942, having achieved their objective of slowing the Japanese advance.

Background

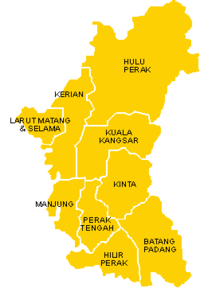

The site overlooking Kampar is set on what is now called Green Ridge. That ridge, together with the nearby Thompson, Kennedy and Cemetery Ridges overlook the main road to the south from Ipoh, Perak, and were of great strategic value. The ridges sit on top of the Gunung Bujang Melaka, a 4,070 foot limestone mountain. This jungle-covered mountain offered a clear view of the surrounding plains covered with open tin mining sites and swamps. The Gunung Bujang Melaka lies to the east of the town of Kampar, its steep slopes leading down to the Kampar Road. With this town and the mountain under control, the Japanese Army would have an excellent view of the Kinta Valley to the south. Allied forces knew that if the 5th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army captured Kampar, they would also be able to use it as a foothold into the Kinta Valley.[2]

With the beginning of General Tomoyuki Yamashita's 25th Army invasion of Malaya the III Indian Corps, defending the north of Malaya, was forced into a series of costly retreats southwards. The outcome of these retreats, ordered by Malaya Command, was a badly mauled and decimated British infantry. The losses suffered by the 11th Indian Division in the battles at Jitra, Kroh, Alor Star and Gurun meant that the division's British and Indian battalions had mostly been amalgamated. After the loss of Kedah province the 12th Indian Infantry Brigade (Malaya Command reserve force and well trained in jungle warfare) replaced the 11th Division and commenced a very successful fighting withdrawal to the Kampar position, inflicting heavy casualties on the Japanese spearhead units.[2] The 12th Brigade's job was to buy time for the re-organisation of the 11th Division and the preparation of defences at Kampar.[3]

British positions

Of the three brigades from the 11th Indian Division, two—the 6th and 15th Indian Infantry Brigades—had been amalgamated to form the 15th/6th Brigade under Brigadier Henry Moorhead (commander of Krohcol). The 15th/6th Brigade now consisted of the survivors from the 1st Leicestershire Regiment and 2nd East Surreys (which had been amalgamated to form the British Battalion), and a composite Jat-Punjab Regiment (formed from survivors of the 1/8th Punjab Regiment and the 2/9th Jat Regiment). The remaining regiments of the brigade—1/14th Punjab, 5/14th Punjab and 2/16th Punjab Regiments—covered the rear of the Kampar position. With all of those regiments in one formation the 15th/6th Brigade still only numbered about 1,600 men. The 28th Gurkha Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Ray Selby, though intact, was low in strength and morale; its three Gurkha battalions had suffered heavy casualties in the fighting around Jitra, Kroh, Gurun and at Ipoh.[2]

Major General Archie Paris (temporary commander of the 11th Division) had to defend a line from the coast through Telok Anson (now Telok Intan) up to the defensive positions at Kampar. The defensive perimeter at Kampar was an all round position, straddling Kampar Hill (Gunong Brijang Malaka) to the east of Kampar town, overlooking the Japanese advance and well concealed by thick jungle. Paris placed artillery spotters on the forward slopes protected by the 15th/6th Brigade on the western side of the position, and the 28th Gurkha Brigade covered the right flank on the eastern side.[2] The two brigades were supported by the 88th Field Artillery Regiment, which was equipped with 25 pounders, and the 4.5 inch howitzers of the 155th Field Artillery Regiment. Once the 12th Brigade had passed through Kampar Paris sent them to cover the coast and his line of retreat at Telok Anson.[2]

Japanese positions

The Japanese attacking force came from Lieutenant General Takuro Matsui's Japanese 5th Division. The intact and relatively fresh 41st Infantry Regiment (about 4,000 strong) from Major General Saburo Kawamura's 9th Brigade spearheaded the attack on Kampar Hill. Kawamura's brigade consisted of Colonel Watanabe's 11th Regiment and Colonel Kanichi Okabe's 41st Regiment.[4]

Battle

Kampar

On 30 December Kawamura's brigade arrived and began encircling and probing the British positions. On the 31 December Kawamura launched probing attacks on the 28th Gurkha Brigade's position on the right flank with a battalion from Watanabe's 11th Regiment. Once the well concealed Gurkhas' positions were found the Japanese formed up to attack and the howitzers of the 155th (Lanarkshire Yeomanry) Field Artillery opened up a concentrated fire on the Japanese troops.[2] All through 31 December the 11th Regiment attacks were beaten off by the Gurkhas and the close support artillery fire. On midnight of New Year's Eve the commander of the 155th Field Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Augustus Murdoch, "ordered a twelve gun salute to be fired at the Japanese".[5]

At seven in the morning, on 1 January 1942, Kawamura launched his main attack against the western side of the Kampar position.[2] This attack was carried out by the 41st Regiment and the brunt of it was against the area held by Lieutenant Colonel Esmond Morrison's British Battalion. The 41st Regiment attacked straight into the British Battalion's positions, supported by heavy mortar fire.[2] The fighting became fierce with Japanese and British positions taken and retaken at the point of a bayonet. Japanese casualties were heavy with a continuous stream of wounded passing Colonel Okabe's headquarters.[2] Combined with the infantry assaults the Japanese poured continuous artillery fire and bombed and strafed the British positions with impunity (the Japanese had nearly complete air superiority by this stage in the campaign). Matsui brought in fresh soldiers to replace his mounting casualties. The well concealed and dug in 15th/6th Brigade, supported by the 88th (2nd West Lancashire) Field Artillery, held on to their positions throughout the two days of fierce fighting on the western slopes of Kampar Hill without relief.[2]

The ferocity and confusion of the close-quarter fighting around the British Battalion was especially violent in the forward positions. Lieutenant Edgar Newland, commanding a platoon of 30 Leicesters, held the most forward position of the battalion. His platoon was surrounded and cut off for most of the battle but Newland and his men fought off all attacks and kept hold of their isolated position throughout the two days. For his actions Newland later received the Military Cross.[2]

During the two-day battle Japanese troops managed to capture trenches on the eastern sector of Thompson Ridge.[6] After two counter-attacks by D Company of the British Battalion and a third by the Jat-Punjab Battalion failed, a reserve mixed company of 60 Sikhs and Gujars from the Jat-Punjab Battalion was brought in to attempt to retake the trenches. This half company under the command of Captain John Onslow Graham and Lieutenant Charles Douglas Lamb (both officers were from 1/8th Punjab) fixed bayonets and charged the Japanese position. The Japanese fire was so heavy that 33 men, including Lamb, were killed in the charge. Graham continued to lead the attack after being wounded and only stopped when a grenade mangled both his legs beneath the knees. Nevertheless, he continued to shout encouragement to his men and was seen throwing grenades at the Japanese trenches. Altogether 34 Indians died in the attack but they retook the position. Graham died of his wounds a day later and was subsequently Mentioned in Dispatches for his actions on Thompson Ridge.[6]

Telok Anson

Matsui realised that the British position at Kampar was too strong for him to take, so General Yamashita ordered landings on the west coast south of Kampar near the 12th Brigade positions at Telok Anson in order to out flank and cut off the line of retreat of the 11th Division. The 11th Infantry Regiment were to land at Hutan Melintang and attack Telok Anson from the south and a force from the Imperial Guards Division headed overland, following the Perak River to attack Telok Anson from the north.[7][8]

The landings were successful and Telok Anson was taken after a brisk battle with the 3rd Cavalry and 1st Independent Company on 2 January 1942. Once Telok Anson had fallen the 3rd Cavalry and 1st Independent Company fell back to the 12th Brigade which successfully delayed the Japanese from taking the main north–south road. Major-General Paris, with his line of retreat threatened, ordered the positions at Kampar to be abandoned. The 12th Brigade covered the retreat of 11th Division and the British pulled back to the next prepared defensive position at Slim River.[2]

Aftermath

Over the four-day period, between 30 December 1941 and 2 January 1942, the 11th Division managed to fight off determined Japanese attacks and inflicted heavy casualties upon them. Such were the Japanese losses that the 41st Infantry Regiment was unable to participate in the later invasion of Singapore. Japanese newspapers at the time claimed 500 Japanese casualties against an Allied loss of 150, but there was no official release of actual Japanese casualties.[9] It was the first serious defeat the Japanese had experienced in the Malayan campaign. Even though the battle was a success for the Allies, the lack of reserves in Malaya Command to support the 11th Division forced the division's withdrawal towards the Slim River.[10][11]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ken, Orrill. "Remembering the Battle of Kampar". Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning. pp. 306–317. ISBN 978-0-14-101036-6.

- ↑ Thompson, Peter (2005). The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II. London: Portrait. p. 185. ISBN 0-7499-5085-4.

- ↑ Thompson pg. 155 and 187

- ↑ Smith pg. 304–305

- 1 2 Loong, Chye Kooi. "Battle of Kampar". Khalsa Diwan Malayasia. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ↑ Thompson pg. 187

- ↑ Owen, Frank (2001) [1960]. The Fall of Singapore. London: Penguin. p. 94.

- ↑ Warren, Alan (2006). Britain's Greatest Defeat: Singapore 1942 (Illustrated ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1-85285-597-5.

- ↑ Thompson pg. 187–188

- ↑ Owen pg. 94–95

References

- Owen, Frank (2001) [1960]. The Fall of Singapore. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-139133-5.

- Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning. England: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101036-6.

- Thompson, Peter (2005). The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II. London: Portrait. ISBN 0-7499-5085-4.

- Warren, Alan (2006). Britain's Greatest Defeat – Singapore 1942. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1-85285-597-5.

Further reading

- Jeffreys, Alan; Anderson, Duncan (2005). British Army in the Far East 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-790-5.

External links

- The Battles of Kampar by Chye Kooi Loong

- Remembering the Battle of Kampar : The Forgotten Heroes of The British Battalion.