Anti-Catholicism in the United States

Anti-Catholicism in United States was deeply rooted in the anti-Catholic attitudes of Protestants in Great Britain and Germany after the Reformation. Immigrants brought that hostility with them to the American colonies. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the theological heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the Biblical Anti-Christ and the Whore of Babylon variety and dominated anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second type was a secular variety which focused on the alleged intrigues of Catholic states which were hostile to both Marxism and Classical Liberalism.[1]

Historians have studied the motivations for anti-Catholicism. Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. characterized prejudice against the Catholics as "the deepest bias in the history of the American people."[2] Conservative writer Peter Viereck once commented that (in 1960) "Catholic baiting is the anti-Semitism of the liberals."[3] Historian John Higham described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history".[4]

After 1980, the historic tensions between evangelical Protestants and Catholics faded dramatically. In politics the two often joined together in conservative social and cultural issues, such as opposition to gay marriage. In 2000, the Republican coalition included almost half of Catholics and a large majority of white evangelicals.[5]

Origins

American Anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Reformation. Because the Reformation was based on an effort to correct what was perceived as the errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, its proponents formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy in general and the Papacy in particular. These positions were held by most Protestant spokesmen in the colonies, including those from Calvinist, Anglican and Lutheran traditions. Furthermore, English and Scottish identity to a large extent was based on opposition to Catholicism. "To be English was to be anti-Catholic," writes Robert Curran.[6]

Many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England whose doctrines and modes of worship were firmly rooted in the Roman Church. Because of this, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia."[7] Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics having any political power. Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could bring together Anglican and Puritan clergy and laity despite their many other disagreements.

In 1642, the Colony of Virginia enacted a law prohibiting Catholic settlers. Five years later, a similar statute was enacted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

In 1649 the Act of Toleration was passed, where "blasphemy and the calling of opprobrious religious names" became punishable offenses, but it was repealed in 1654 and thus Catholics were outlawed once again. By 1692, formerly Catholic Maryland overthrew its Government, established the Church of England by law, and forced Catholics to pay heavy taxes towards its support. They were cut off from all participation in politics and additional laws were introduced that outlawed the Mass, the Church's Sacraments, and Catholic schools.

In 1719, Rhode Island imposed civil restrictions on Catholics.[8]

Pennsylvania became a safe haven for Catholic refugees from Maryland. William Penn had been harassed as a Quaker, and he enacted a broad grant of religious toleration and civil rights to all who believed in God, regardless of their particular denomination. The threat of war between England and France brought about renewed suspicions against Catholics. However, the Quaker government in Pennsylvania refused to be coerced into violating its traditional policies.

John Adams attended a Catholic Mass in Philadelphia one day in 1774. He praised the sermon for teaching civic duty, and enjoyed the music, but ridiculed the rituals engaged in by the parishioners.[9] In 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce the pope and foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil," which included both the Catholic and the Anglican churches.[10]

Once the Revolution was underway and independence was at hand, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Maryland passed acts of religious toleration in 1776.[11] George Washington, as commander of the army and as president, was a vigorous promoter of tolerance for all religious denominations. He believed religion was an important support for public order, morality and virtue. He often attended services of different denominations. He suppressed anti-Catholic celebrations in the Army.[12]

19th century

In 1836, Maria Monk's Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery in Montreal was published. It was a great commercial success and is still circulated today by such publishers as Jack Chick. It was discovered to be a fabrication shortly after publication.[13] It was the most prominent of many such pamphlets. Numerous ex-priests and ex-nuns were on the anti-Catholic lecture circuit with lurid tales, always involving heterosexual contacts of adults—priests and nuns with dead babies buried in the basement.[14]

Immigration

Anti-Catholicism reached a peak in the mid nineteenth century when Protestant leaders became alarmed by the heavy influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany. Some believed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation.[15]

In his best-selling book of fiction, A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur's Court (1889), author Mark Twain indicates his hostility to the Catholic Church.[16] He admitted that he had "...been educated to enmity toward everything that is Catholic."[17]

Nativism

In the 1830s and 1840s, prominent Protestant leaders, such as Lyman Beecher and Horace Bushnell, attacked the Catholic Church as not only theologically unsound but an enemy of republican values.[18] Some scholars view the anti-Catholic rhetoric of Beecher and Bushnell as having contributed to anti-Irish and anti-Catholic pogroms.[19]

Beecher's well-known Plea for the West (1835) urged Protestants to exclude Catholics from western settlements. The Catholic Church's official silence on the subject of slavery also garnered the enmity of northern Protestants. Intolerance became more than an attitude on August 11, 1834, when a mob set fire to an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics.[20] This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for spreading violence and drunkenness.[21]

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

Public funding of parochial schools

.jpg)

Catholic schools began in the United States as a matter of religious and ethnic pride and as a way to insulate Catholic youth from the influence of Protestant teachers and contact with non-Catholic students.[22]

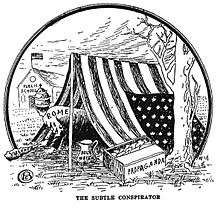

In 1869 the religious issue in New York City escalated when Tammany Hall, with its large Catholic base, sought and obtained $1.5 million in state money for Catholic schools. Thomas Nast's cartoon The American River Ganges (above) shows Catholic Bishops, directed by the Vatican, as crocodiles attacking American schoolchildren.[23][24]

Republican Senator James G. Blaine of Maine proposed an amendment to the Constitution in 1874 that provided: "No money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public source, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised or land so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations." The amendment was defeated in 1875 but would be used as a model for so-called "Blaine Amendments" incorporated into 34 state constitutions over the next three decades.

In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant supported the Blaine Amendment – a Constitutional amendment that would mandate free public schools and prohibit the use of public funds for "sectarian" schools. Grant feared a future with "patriotism and intelligence on one side and superstition, ambition and greed on the other" and called for public schools that would be "unmixed with atheistic, pagan or sectarian teaching."[25]

These "Blaine amendments" prohibited the use of public funds to fund parochial schools.[26]

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Catholic.

1910s

Anti-Catholic sentiment was popular enough that The Menace, a weekly newspaper with a virulently anti-Catholic stance, was founded in 1911 and quickly reached a nationwide circulation of 1.5 million.

1920s

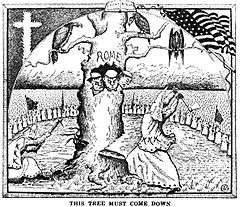

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in the 1920s; anti-Catholics, including the Ku Klux Klan, believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that parochial schools encouraged separatism and kept Catholics from becoming loyal Americans. The Catholics responded to such prejudices by repeatedly asserting their rights as American citizens and by arguing that they, not the nativists (anti-Catholics), were true patriots since they believed in the right to freedom of religion.[27]

With the rapid growth of the second Ku Klux Klan (KKK) 1921–25, anti-Catholic rhetoric intensified. The Catholic Church of the Little Flower was first built in 1925 in Royal Oak, Michigan, a largely Protestant area. Two weeks after it opened, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of the church.[28]

In Alabama, Hugo Black was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1926 having built a political base in part through 148 speeches at local Klan gatherings, where his focus was the denunciation of Catholicism.[29] Howard Ball characterizes Black as having "sympathized with the [Klan's] economic, nativist, and anti-Catholic beliefs."[30] As a Supreme Court justice, Black has been accused of letting his anti-Catholic bias influence key decisions regarding the separation of church and state. For example, Christianity Today editorialized that, "Black's advocacy of church-state separation, in turn, found its roots in the fierce anti-Catholicism of the Masons and the Ku Klux Klan (Black was a Kladd of the Klavern, or an initiator of new members, in his home state of Alabama in the early 1920s)."[31] A leading Constitutional scholar,[32] Professor Philip Hamburger of Columbia University Law School, has strongly called into question Black's integrity on the church-state issue because of his close ties to the KKK. Hamburger argues that his views on the need for separation of Church and State were deeply tainted by his membership in the Ku Klux Klan, a vehemently anti-Catholic organization.[33]

Supreme Court upholds parochial schools

In 1922, the voters of Oregon passed an initiative amending Oregon Law Section 5259, the Compulsory Education Act. The law unofficially became known as the Oregon School Law. The citizens' initiative was primarily aimed at eliminating parochial schools, including Catholic schools.[34] The law caused outraged Catholics to organize locally and nationally for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925), the United States Supreme Court declared the Oregon's Compulsory Education Act unconstitutional in a ruling that has been called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system."

1928 Presidential election

The Klan collapsed in the mid-1920s. It had been denounced by most newspapers and had few prominent defenders. It was disgraced by scandals at high levels and weakened by its pyramid-scheme system whereby organizers collected fees and then abandoned local chapters. By 1930 only a few small local chapters survived. No later national nativist organization ever achieved even a tiny fraction of the Klan membership.[35]

In 1928, Al Smith became the first Roman Catholic to gain a major party's nomination for president, and his religion became an issue during the campaign. His nomination made anti-Catholicism a rallying point especially for Lutheran and Southern Baptist ministers. They warned that national autonomy would be threatened because Smith would be listening not to the American people but to secret orders from the pope. There were rumors the pope would move to the United States to control his new realm.[36]:309–310

Across the country, and especially in strongholds of the Lutheran, Baptist and Fundamentalist churches, Protestant ministers spoke out. They seldom endorsed Republican Herbert Hoover, who was a Quaker. More often they alleged Smith was unacceptable. A survey of 8,500 Southern Methodist ministers found only four who publicly supported Smith. Many Americans who sincerely rejected bigotry and the Klan justified their opposition to Smith because, they believed the Catholic Church was an "un-American" and "alien culture" that opposed freedom and democracy.[36]:311–312 The National Lutheran Editors' and Managers' Association opposed Smith's election in a manifesto written by Dr. Clarence Reinhold Tappert. It warned about, "the peculiar relation in which a faithful Catholic stands and the absolute allegiance he owes to a 'foreign sovereign' who does not only 'claim' supremacy also in secular affairs as a matter of principle and theory but who, time and again, has endeavored to put this claim into practical operation." The Catholic Church, the manifesto asserted, was hostile to American principles of separation of church and state and of religious toleration.[37] Prohibition had widespread support in rural Protestant areas, and Smith's wet position, as well as his long-time sponsorship by Tammany Hall compounded his difficulties there. He was weakest in the border states; the day after Smith gave a talk pleaded for brotherhood in Oklahoma City, the same auditorium was jammed for an evangelist who lectured on "Al Smith and the Forces of Hell."[38] Smith picked Senator Joe Robinson, a prominent Arkansas Senator as his running mate. When the pro-Smith Democrats raised the race issue against the Republicans they were able to contain their losses in the Black Belt (areas with black majorities but where only whites voted) so Smith carried the Deep South—the area long identified with anti-Catholicism. Efforts by Senator Tom Heflin to recycle his long-standing attacks on the pope failed in Alabama.[39] Smith's strong anti-Klan position resonated across the country with voters who thought the KKK was a real threat to democracy.[40] Smith split the South, carrying the Deep South while losing the periphery. After 1928 the Solid South returned to the Democratic fold.[41] One long-term result was the surge in Democratic voting in the large cities, as ethnic Catholics went to the polls to defend their religious culture, often bringing their women to the polls for the first time. The nation's twelve largest cities gave pluralities of 1.6 million to the GOP in 1920, and 1.3 million in 1924; now they went for Smith by a whisker-thin 38,000 votes, while everywhere else was for Hoover. The surge proved permanent. as Catholics comprised a major portion of the New Deal Coalition that Franklin D. Roosevelt assembled and which dominated national elections for decades.[42]

New Deal

President Franklin D. Roosevelt depended heavily in his four elections on the Catholic vote and the enthusiasm of Irish machines in major cities such as Boston, Chicago and New York. Al Smith and many of Smith's associates broke with FDR and formed the American Liberty League, which represented big business opposition to the New Deal. Catholic radio priest Charles Coughlin supported FDR in 1932, but broke with him in 1935 and made weekly attacks. There were few senior Catholics in the New Deal—the most important were Postmaster General James Farley (who broke with FDR in 1940) and Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. (who was on the verge of breaking in 1940 but finally supported FDR in the interest of his sons).

In foreign policy the Catholics demanded American neutrality regarding the Spanish Civil War, and were joined by isolationists. Liberals wanted American help to the anti-Catholic Loyalist cause, but FDR kept the nation neutral.[43]

The second most serious issue arose with the renewed anti-Catholic campaign in Mexico. American Catholics bitterly attacked Ambassador Josephus Daniels for failing to combat the virulent attacks on the Catholic Church by the Mexican government.[44] Daniels was a staunch Methodist and worked well with Catholics in the U.S., but he had little sympathy for the Church in Mexico, feeling it represented the landed aristocracy that stood opposed to his version of liberalism. For the same reason he supported the Loyalist cause in the Spanish Civil War, which was even more intensely anti-Catholic. The main issue was the government's efforts to shut down Catholic schools in Mexico; Daniels publicly approved the attacks, and saluted virulently anti-Catholic Mexican politicians. In a July 1934 speech at the American Embassy, Daniels praised the anti-Catholic efforts led by former president Calles:

General Calles sees, as Jefferson saw, that no people can be both free and ignorant. Therefore, he and President Rodriguez, President-elect Cairdenas and all forward-looking leaders are placing public education as the paramount duty of the country. They all recognize that General Calles issued a challenge that goes to the very root of the settlement of all problems of tomorrow when he said: "We must enter and take possession of the mind of childhood, the mind of youth."[45]

In 1935, Senator William Borah of Idaho, the chief Republican specialist on foreign policy, called for a Senate investigation of anti-Catholic government policies in Mexico. He came under a barrage of attacks from leading Protestant organizations, including the Federal Council of Churches, the Episcopal Church, and the board of foreign missions of the Methodist Church. There was no Senate investigation. A call for an investigation signed by 250 members of the House was blocked by Roosevelt. The Knights of Columbus began attacking Roosevelt. The crisis ended with Mexico turning away from the Calles hard line policies, perhaps in response to Daniels' backstage efforts. Roosevelt easily won all the Catholic strongholds in his 1936 landslide.[46]

World War II

World War II was the decisive event that brought religious tolerance to the front in American life. Bruscino says "the military had developed personnel policies that actively and completely mixed America's diverse white ethnic and religious population. The sudden removal from the comforts of home, the often degrading and humiliating experiences of military life, and the unit-and friendship-building of training leveled the man the activities meant to fill time support of in the military reminded the man of all they had in common as Americans. Under fire, the men survived by leaning on buddies, regardless of their ethnicity or religion." After coming home, the veterans helped reshape American society. Brucino says that they used their positions of power "to increase ethnic and religious tolerance. The sea change in ethnic and religious relations in the United States came from the military experience in World War II. The war remade the nation. The nation was forged in war."[47]

Elites: Vice President Wallace and Eleanor Roosevelt

At the elite level, tolerance of Catholicism was more problematic. Henry A. Wallace, Roosevelt's vice-president in 1941-45, did not go public with his anti-Catholicism, but he often expounded it in his diary, especially during and after World War II. He briefly attended a Catholic church in the 1920s, and was disillusioned by what he perceived to be the intellectual straitjacket of Thomism.[48] By the 1940s, he worried that certain "bigoted Catholics" were scheming to take control of the Democratic Party; indeed the Catholic big city bosses in 1944 played a major role in denying him renomination as vice present.[49] He confided in his diary that it was "increasingly clear" that the State Department intended "to save American boys lives by handing the world over to the Catholic Church and saving it from communism."[50] In 1949, Wallace opposed NATO, warning that "certain elements in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church" were involved in a pro-war hysteria.[51] Defeated for the presidency in his third-party run in 1948, Wallace blamed Tory Britain, the Roman Catholic Church, Reactionary Capitalism, and various others for his overwhelming defeat.[52]

Eleanor Roosevelt, the president's widow, and other New Deal liberals who were fighting Irish-dominated Democratic parties, feuded publicly with Church leaders on national policy. They accused her of being anti-Catholic.

In July 1949, Roosevelt had a public disagreement with Francis Joseph Spellman, the Catholic Archbishop of New York, which was characterized as "a battle still remembered for its vehemence and hostility".[53][54] In her columns, Roosevelt had attacked proposals for federal funding of certain nonreligious activities at parochial schools, such as bus transportation for students. Spellman cited the Supreme Court's decision which upheld such provisions, accusing her of anti-Catholicism. Most Democrats rallied behind Roosevelt, and Spellman eventually met with her at her Hyde Park home to quell the dispute. However, Roosevelt maintained her belief that Catholic schools should not receive federal aid, evidently heeding the writings of secularists such as Paul Blanshard.[53] Privately, Roosevelt said that if the Catholic Church gained school aid, "Once that is done they control the schools, or at least a great part of them."[53]

During the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, Eleanor Roosevelt favored the republican Loyalists against General Francisco Franco's Nationalists; after 1945, she opposed normalizing relations with Spain.[55] She told Spellman bluntly that "I cannot however say that in European countries the control by the Roman Catholic Church of great areas of land has always led to happiness for the people of those countries."[53] Her son Elliott Roosevelt suggested that her "reservations about Catholicism" were rooted in her husband's sexual affairs with Lucy Mercer and Missy LeHand, who were both Catholics.[56]

Roosevelt's biographer Joseph P. Lash denies that she was anti-Catholic, citing her public support of Al Smith, a Catholic, in the 1928 presidential campaign and her statement to a New York Times reporter that year quoting her uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt, in expressing "the hope to see the day when a Catholic or a Jew would become president".[57]

In 1949, Paul Blanshard wrote in his bestselling book American Freedom and Catholic Power that America had a "Catholic Problem". He stated that the Church was an "undemocratic system of alien control" in which the lay were chained by the "absolute rule of the clergy." In 1951, in Communism, Democracy, and Catholic Power, he compared Rome with Moscow as "two alien and undemocratic centers", including "thought control".[58]

1950s

On October 20, 1951, President Harry Truman nominated former General Mark Clark to be the United States emissary to the Vatican. Clark was forced to withdraw his nomination on January 13, 1952, following protests from Texas Senator Tom Connally and Protestant groups.

In the 1950s prejudices against Catholics could still be heard from some Protestant ministers, but national leaders increasingly tried to build up a common front against communism and stressed the common values shared by Protestants, Catholics and Jews. Leaders like Dwight D. Eisenhower emphasized how Judeo-Christian values were a central component of American national identity.[59]

1960 election

A key factor that affected the vote for and against John F. Kennedy in his 1960 campaign for the presidency of the United States was his Catholic religion. Catholics mobilized and gave Kennedy from 75 to 80 percent of their votes.[60] Some Protestant spokesmen, such as Norman Vincent Peale, still feared the Pope would be giving orders to a Kennedy White House.[61] To allay such fears, Kennedy kept his distance from church officials and in a highly publicized confrontation told the Protestant ministers of the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters – and the Church does not speak for me."[62] He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to allow Church officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy counterattacked by suggesting that it was bigotry to relegate one-quarter of all Americans to second-class citizenship just because they were Catholic. In the final count, the additions and subtractions to Kennedy's vote because of religion probably canceled out. He won a close election; The New York Times reported a "narrow consensus" among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost as a result of his Catholicism,[63] as Catholics flocked to Kennedy to demonstrate their group solidarity in demanding political equality.

1990 – 21st century

After 1980 the historic tensions between evangelical Protestants and Catholics faded dramatically.[5] In politics the two often joined together in fighting for conservative social and cultural issues, such as the Pro-Life and traditional marriage movements. Both groups held tightly to traditional moral values and opposed secularization. Ronald Reagan was especially popular among both evangelicals and ethnic Catholics known as Reagan Democrats. By 2000 the Republican coalition included about half the Catholics and a large majority of white evangelicals.[64]

In 1980 the New York Times warned the Catholic Bishops that if they followed the church's instructions and denied communion to politicians who advocated a pro-choice position regarding abortion they would be "imposing a test of religious loyalty" that might jeopardize "the truce of tolerance by which Americans maintain civility and enlarge religious liberty".[65]

Starting in 1993, members of Historic Adventist splinter groups paid to have anti-Catholic billboards that called the Pope the Antichrist placed in various cities on the West Coast, including along Interstate 5 from Portland to Medford, Oregon, and in Albuquerque, New Mexico. One such group took out an anti-Catholic ad on Easter Sunday in The Oregonian, in 2000, as well as in newspapers in Coos Bay, Oregon and in Longview and Vancouver, Washington. Mainstream Seventh-day Adventists denounced the advertisements. The contract for the last of the billboards in Oregon ran out in 2002.[66][67][68][69][70]

Philip Jenkins, an Episcopalian historian, maintains that some who otherwise avoid offending members of racial, religious, ethnic or gender groups have no reservations about venting their hatred of Catholics.[71]

In May 2006, a Gallup poll found 57% of Americans had a favorable view of the Catholic faith, while 30% of Americans had an unfavorable view. The Catholic Church's doctrines, and the priest sex abuse scandal were top issues for those who disapproved. "Greed", Roman Catholicism's view on homosexuality, and the celibate priesthood were low on the list of grievances for those who held an unfavorable view of Catholicism.[72] While Protestants and Catholics themselves had a majority with a favorable view, those who are not Christian or are irreligious had a majority with an unfavorable view. In April 2008, Gallup found that the number of Americans saying they had a positive view of U.S. Catholics had shrunk to 45% with 13% reporting a negative opinion. A substantial proportion of Americans, 41%, said their view of Catholics was neutral, while 2% of Americans indicated that they had a "very negative" view of Roman Catholics. However, with a net positive opinion of 32%, sentiment towards Catholics was more positive than that for both evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, who received net-positive opinions of 16 and 10% respectively. Gallup reported that Methodists and Baptists were viewed more positively than Catholics, as were Jews.[73]

Human sexuality, contraception and abortion

LGBT activists and others criticize the Catholic Church for its teachings on issues relating to human sexuality, contraception and abortion.

In 1989, members of ACT UP and WHAM! disrupted a Sunday Mass at Saint Patrick's Cathedral to protest the Church's position on homosexuality, sex education and the use of condoms. The protestors desecrated Communion hosts. According to Andrew Sullivan, "Some of the most anti-Catholic bigots in America are gay".[74] One hundred eleven protesters were arrested outside the Cathedral.[75]

On January 30, 2007, John Edwards' presidential campaign hired Amanda Marcotte as blogmaster.[76] The Catholic League, which is not an official organ of the Catholic Church, took offense at her obscenity- and profanity-laced invective against Catholic doctrine and satiric rants against Catholic leaders, including some of her earlier writings, where she described sexual activity of the Holy Spirit and claimed that the Church sought to "justify [its] misogyny with [...] ancient mythology."[77] The Catholic League publicly demanded that the Edwards campaign terminate Marcotte's appointment. Marcotte subsequently resigned, citing "sexually violent, threatening e-mails" she had received as a result of the controversy.[78]

Anti-Catholicism in the entertainment industry

According to Fr. James Martin, S.J. the U.S. entertainment industry is of "two minds" about the Catholic Church. He argues that:

On the one hand, film and television producers seem to find Catholicism irresistible. There are a number of reasons for this. First, more than any other Christian denomination, the Catholic Church is supremely visual, and therefore attractive to producers and directors concerned with the visual image. Vestments, monstrances, statues, crucifixes – to say nothing of the symbols of the sacraments – are all things that more "word oriented" Christian denominations have foregone. The Catholic Church, therefore, lends itself perfectly to the visual media of film and television. You can be sure that any movie about the Second Coming or Satan or demonic possession or, for that matter, any sort of irruption of the transcendent into everyday life, will choose the Catholic Church as its venue. (See, for example, End of Days, Dogma or Stigmata.)

Second, the Catholic Church is still seen as profoundly "other" in modern culture and is therefore an object of continuing fascination. As already noted, it is ancient in a culture that celebrates the new, professes truths in a postmodern culture that looks skeptically on any claim to truth, and speaks of mystery in a rational, post-Enlightenment world. It is therefore the perfect context for scriptwriters searching for the "conflict" required in any story.[79]

He argues that, despite this fascination with the Catholic Church, the entertainment industry also holds contempt for the Church. "It is as if producers, directors, playwrights and filmmakers feel obliged to establish their intellectual bona fides by trumpeting their differences with the institution that holds them in such thrall."[79]

References

- ↑ Mannard, Joseph G. (1981). American Anti-Catholicism and its Literature.

- ↑ John Tracy Ellis, "American Catholicism", University Of Chicago Press 1956.

- ↑ Herberg, Will. "Religion in a Secularized Society: Some Aspects of America's Three-Religion Pluralism", Review of Religious Research, vol. 4 no. 1, Autumn, 1962, p. 37

- ↑ Jenkins, Philip (April 1, 2003). The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-19-515480-0.

- 1 2 William M. Shea, The Lion and the Lamb: Evangelicals and Catholics in America (Oxford University Press, 2004)

- ↑ Robert Emmett Curran, Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574–1783 (2014) pp 201-2

- ↑ Ellis, John Tracy (1956). American Catholicism.

- ↑ Marian Horvat. "The Catholic Church in Colonial America by Dr. Marian T. Horvat". traditioninaction.org. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ The American Catholic Historical Researches. 15. M.I.J. Griffin. 1898. p. 174. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ Annotation

- ↑ John Tracy Ellis (1969). American Catholicism. U of Chicago Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Paul F. Boller, "George Washington and Religious Liberty." William and Mary Quarterly (1960): 486-506. in JSTOR

- ↑ Ray Allen Billington, "Maria Monk and her influence." Catholic Historical Review (1936): 283-296. in JSTOR

- ↑ Marie Anne Pagliarini, "The pure American woman and the wicked Catholic priest: An analysis of anti-Catholic literature in antebellum America." Religion and American Culture (1999): 97-128. in JSTOR

- ↑ Bilhartz, Terry D. (1986). Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-8386-3227-0.

- ↑ "Yankee Anti-Catholicism". MT, His Time, Catholic Church. Virginia.edu. September 11, 2010.

- ↑ Twain, M. (2008). The Innocents Abroad. Velvet Element. p. 599. ISBN 9780981764467. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ Beecher, Lyman (1835). A Plea for the West. Cincinnati: Truman & Smith. p. 61. ISBN 0-405-09941-X. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

The Catholic system is adverse to liberty, and the clergy to a great extent are dependent on foreigners opposed to the principles of our government, for patronage and support.

- ↑ Matthews, Terry. "Lecture 16 – Catholicism in Nineteenth Century America". Retrieved April 3, 2009.Stravinskas, Peter, M.J., Shaw, Russell (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Encyclopedia. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87973-669-9.

- ↑ Jimmy Akin (March 1, 2001). "The History of Anti-Catholicism". This Rock. Catholic Answers. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- ↑ Hennesey, James J. (1983). American Catholics. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-19-503268-0.

- ↑ James W. Sanders, The Education of an Urban Minority (1977), pp. 21, 37–8.

- ↑ Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2005). Boss Tweed. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-7867-1686-9.

- ↑ Thomas, Samuel J. (2004). "Mugwump Cartoonists, the Papacy, and Tammany Hall in America's Gilded Age". Religion and American Culture. 14 (2): 243. doi:10.1525/rac.2004.14.2.213. ISSN 1052-1151. JSTOR 4148267.

- ↑ David B. Tyack and Elisabeth Hansot, Managers of virtue: public school leadership in America, 1820–1980 (1986) Page 77 online

- ↑ In 2002, the Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, in theory, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school, even if it were religious. However, as of 2010, no state school system had changed its laws to allow state funds to be used for this purpose. Bush, Jeb (March 4, 2009). NO: Choice forces educators to improve. The Atlanta Constitution-Journal.

- ↑ Dumenil (1991)

- ↑ Shannon, William V. (1989) [1963]. The American Irish: a political and social portrait. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-87023-689-1. OCLC 19670135.

- ↑ Roger K. Newman, Hugo Black: a biography (1997) pp 87, 104

- ↑ Howard Ball, Hugo L. Black: cold steel warrior (1996) p. 16

- ↑ "'A Crack in the Wall: Two recent books help explain Thomas Jefferson's intent for separation of church and state," Christianity Today Editorial Oct 7, 2002 online

- ↑ "A leading US constitutional historian, Philip Hamburger," writes Martha Nussbaum, Liberty of conscience (2008) p 120

- ↑ Philip Hamburger, Separation of Church and State (2002) pp 422–28

- ↑ Howard, J. Paul. "Cross-Border Reflections, Parents' Right to Direct Their Children's Education Under the U.S. and Canadian Constitutions", Education Canada, v41 n2 p36-37 Sum 2001.

- ↑ David Joseph Goldberg (1999). Discontented America: The United States in the 1920s. Johns Hopkins U.P. pp. 139–40.

- 1 2 Slayton, Robert A. (2001). Empire statesman: the rise and redemption of Al Smith. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-86302-2.

- ↑ Douglas C. Strange, "Lutherans and Presidential Politics: The National Lutheran Editors' and Managers' Association Statement of 1928," Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly, Winter 1968, Vol. 41 Issue 4, pp 168–172

- ↑ George J. Marlin, American Catholic Voter: Two Hundred Years of Political Impact (2006) p 184

- ↑ Eddie Weller and Cecil Weller, Joe T. Robinson: Always a Loyal Democrat (1998) p 110

- ↑ John T. McGreevy, Catholicism and American Freedom: A History (2004) p 148

- ↑ Allan J. Lichtman, Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928 (1979)

- ↑ William B. Prendergast, The Catholic Voter in American Politics: The Passing of the Democratic Monolith (1999) pp 96–115

- ↑ J. David Valaik, "Catholics, Neutrality, and the Spanish Embargo, 1937–1939," Journal of American History (1967) 54#1 pp. 73-85 in JSTOR

- ↑ Robert H. Vinca, "The American Catholic Reaction to the Persecution of the Church in Mexico, from 1926–1936," Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia (1968) Issue 1, pp 3-38.

- ↑ E. David Cronon, "American Catholics and Mexican Anticlericalism, 1933–1936," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1958) 45#2 pp. 201-230 in JSTOR; quote p. 207

- ↑ Cronon, "American Catholics and Mexican Anticlericalism, 1933–1936," p 216-25

- ↑ Thomas A. Bruscino (2010). A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along. U. of Tennessee Press. pp. 214–15.

- ↑ John C. Culver and John Hyde, American Dreamer: A Life of Henry a. Wallace (2000), p 77

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, pp 293, 317

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p 292

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p 504

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p 512

- 1 2 3 4 Lash, Joseph P. (1972). Eleanor: The Years Alone. Scarborough, Ont.: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-39307-361-0., pp. 156–65, 282.

- ↑ Beasley, Eleanor Roosevelt Encyclopedia pp. 498–502

- ↑ Beasley, Eleanor Roosevelt Encyclopedia p. 492.

- ↑ Elliot Roosevelt and James Brough (1973) An Untold Story, New York: Dell, p. 282.

- ↑ Eleanor Roosevelt, as quoted in The New York Times, January 25, 1928 by Lash, p. 419.

- ↑ Blanshard, American Freedom and Catholic Power

- ↑ Martin E. Marty, Modern American Religion, Volume 3: Under God, Indivisible, 1941–1960 (1999)

- ↑ Theodore H. White (2009). The Making of the President 1960. HarperCollins. p. 355.

- ↑ Gary Donaldson, The first modern campaign: Kennedy, Nixon, and the election of 1960, p.107

- ↑ Kennedy, John F. (June 18, 2002). "Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association". American Rhetoric. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ↑ New York Times, November 20, 1960, Section 4, p. E5

- ↑ Kristin E. Heyer; et al. (2008). Catholics and Politics: The Dynamic Tension Between Faith and Power. Georgetown University Press. pp. 39–42.

- ↑ "The Bishop and the Truce of Tolerance (editorial)". New York Times. November 26, 1989. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ Langlois, Ed (July 27, 2001). "Spruced-up billboard marks beginning of new 'pope-is-Antichrist' campaign". Catholic Sentinel. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ↑ Mehle, Michael (August 4, 1993). "Billboard Supplier Won't Run Attacks on Pope". Rocky Mountain News. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ↑ Associated Press (December 25, 1993). "Billboard Bashing". Salt Lake Tribune.

- ↑ Langlois, Ed (June 6, 2002). "Billboard contract lapses, 'Pope is Antichrist' remains; more ads planned". Catholic Sentinel. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ↑ Langlois, Ed (April 29, 2000). "Oregonian runs anti-Catholic ad on Easter". Catholic Sentinel. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ↑ Philip Jenkins, The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice. (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 0-19-515480-0)

- ↑ "Religion". Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Americans Have Net-Positive View of U.S. Catholics". April 15, 2008. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ "The Last Acceptable Prejudice? | America Magazine". americamagazine.org. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ "300 Fault O'Connor Role On AIDS Commission - NYTimes.com". query.nytimes.com. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ Marcotte, Amanda (January 30, 2007). "Pandagon changes". Pandagon. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ↑ Catholic League (February 6, 2007). "News Release: John Edwards Hires Two Anti-Catholics". Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Why I had to quit the John Edwards campaign". Salon.com. February 16, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- 1 2 "The Last Acceptable Prejudice". America The National Catholic Weekly. March 25, 2000. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

Additional reading

- Anbinder; Tyler Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s 1992

- Bennett; David H. The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History University of North Carolina Press, 1988

- Billington, Ray. The Protestant Crusade, 1830–1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism (1938)

- Brown, Thomas M. "The Image of the Beast: Anti-Papal Rhetoric in Colonial America", in Richard O. Curry and Thomas M. Brown, eds., Conspiracy: The Fear of Subversion in American History (1972), 1–20.

- Cogliano; Francis D. No King, No Popery: Anti-Catholicism in Revolutionary New England (1995) online edition

- Cuddy, Edward. "The Irish Question and the Revival of Anti-Catholicism in the 1920s," Catholic Historical Review, 67 (April 1981): 236–55.

- Curran, Robert Emmett. Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574–1783 (2014) pp 201–2

- Davis, David Brion. "Some Themes of Counter-subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic and Anti-Mormon Literature", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47 (1960), 205–224.

- Dumenil, Lynn. "The Tribal Twenties: 'Assimilated' Catholics' Response to Anti-Catholicism in the 1920s," Journal of American Ethnic History 1991 11(1): 21–49 in EBSCO

- Greeley, Andrew M. An Ugly Little Secret: Anti-Catholicism in North America 1977.

- Henry, David. "Senator John F. Kennedy Encounters the Religious Question: I Am Not the Catholic Candidate for President." in Contemporary American Public Discourse ed. by H. R. Ryan. (1992). 177–193.

- Hennesey, James. American Catholics: A History of the Roman Catholic Community in the United States (1981),

- Higham; John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 1955

- Hinckley, Ted C. "American Anti-Catholicism During the Mexican War" Pacific Historical Review 1962 31(2): 121–137. ISSN 0030-8684

- Hostetler; Michael J. "Gov. Al Smith Confronts the Catholic Question: The Rhetorical Legacy of the 1928 Campaign" Communication Quarterly. Volume: 46. Issue: 1. 1998. Page Number: 12+.

- Philip Jenkins, The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (Oxford University Press, New ed. 2004). ISBN 0-19-517604-9

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896 (1971)

- Jensen, Richard. "'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization," Journal of Social History 36.2 (2002) 405–429, with illustrations

- Jorgenson, Lloyd P. The State and the Non-Public School 1825–1925 (1987), esp. pp. 146–204;

- Keating, Karl. Catholicism and Fundamentalism – The Attack on "Romanism" by "Bible Christians" (Ignatius Press, 1988). ISBN 0-89870-177-5

- Kenny; Stephen. "Prejudice That Rarely Utters Its Name: A Historiographical and Historical Reflection upon North American Anti-Catholicism." American Review of Canadian Studies. Volume: 32. Issue: 4. 2002. pp : 639+.

- Kinzer, Donald. An Episode in Anti-Catholicism: The American Protective Association (1964), on 1890s

- Lessner, Richard Edward. "The Imagined Enemy: American Nativism and the Disciples of Christ, 1830–1925," (PhD diss., Baylor University, 1981).

- Lichtman, Allan J. Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928 (1979)

- McGreevy, John T. "Thinking on One's Own: Catholicism in the American Intellectual Imagination, 1928–1960." The Journal of American History, 84 (1997): 97–131.

- Moore; Edmund A. A Catholic Runs for President 1956.

- Moore; Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921–1928 University of North Carolina Press, 1991

- Moore; Leonard J. "Historical Interpretations of the 1920s's Klan: The Traditional View and the Populist Revision," Journal of Social History, 24 (Fall 1990): 341–358.

- Page, David P. "Bishop Michael J. Curley and Anti-Catholic Nativism in Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly 45 (October 1966): 101–117

- Thiemann, Ronald F. Religion in Public Life Georgetown University Press, 1996.

- Waldman, Steven (2009). Founding Faith. Random House. ISBN 978-0812974744.

- Wills, Garry. Under God 1990.

- White, Theodore H. The Making of the President 1960 1961.

Primary sources attacking Catholic Church

- Blanshard, Paul. American Freedom and Catholic Power Beacon Press, 1949, an influential attack on the Catholic Church

- Samuel W. Barnum. Romanism as It Is (1872), an anti-Catholic compendium online

- Rev. Isaac J. Lansing, M.A. Romanism and the Republic: A Discussion of the Purposes, Assumptions, Principles and Methods of the Roman Catholic Hierarchy (1890) Online

- Alma White (1928). Heroes of the Fiery Cross. The Good Citizen.

- Alma White (1926). Klansmen: Guardians of Liberty. The Good Citizen.

- Alma White (1925). The Ku Klux Klan In Prophecy. The Good Citizen.

- Zacchello, Joseph. Secrets of Romanism. Neptune, N.J.: Loiseaux Brothers, 1948. viii, 222, [2] p. ISBN 087213-981-6 (added to later printings). N.B.: Polemical work by a former priest who became a celebrated radio-evangelist.