Ammonium

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ammonium | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 14798-03-9 | |||

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image | ||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:CHEBI:28938 | ||

| ChemSpider | 218 | ||

| MeSH | D000644 | ||

| PubChem | 16741146 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| NH+ 4 | |||

| Molar mass | 18.04 g·mol−1 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.25 | ||

| Structure | |||

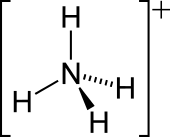

| Tetrahedral | |||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

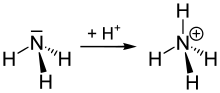

The ammonium cation is a positively charged polyatomic ion with the chemical formula NH+

4.[1] It is formed by the protonation of ammonia (NH3). Ammonium is also a general name for positively charged or protonated substituted amines and quaternary ammonium cations (NR+

4), where one or more hydrogen atoms are replaced by organic groups (indicated by R).

Acid base properties

The ammonium ion is generated when ammonia, a weak base, reacts with Brønsted acids (proton donors):

- H+ + NH3 → NH+

4

The ammonium ion is mildly acidic, reacting with Brønsted bases to return to the uncharged ammonia molecule:

- NH+

4 + B− → HB + NH3

Thus, treatment of concentrated solutions of ammonium salts with strong base gives ammonia. When ammonia is dissolved in water, a tiny amount of it converts to ammonium ions:

- H2O + NH3 ⇌ OH− + NH+

4

The degree to which ammonia forms the ammonium ion depends on the pH of the solution. If the pH is low, the equilibrium shifts to the right: more ammonia molecules are converted into ammonium ions. If the pH is high (the concentration of hydrogen ions is low), the equilibrium shifts to the left: the hydroxide ion abstracts a proton from the ammonium ion, generating ammonia.

Formation of ammonium compounds can also occur in the vapor phase; for example, when ammonia vapor comes in contact with hydrogen chloride vapor, a white cloud of ammonium chloride forms, which eventually settles out as a solid in a thin white layer on surfaces.

The conversion of ammonium back to ammonia is easily accomplished by the addition of a strong base.

Ammonium salts

Ammonium cation is found in a variety of salts such as ammonium carbonate, ammonium chloride, and ammonium nitrate. Most simple ammonium salts are very soluble in water. An exception is ammonium hexachloroplatinate, the formation of which was once used as a test for ammonium. The ammonium salts of nitrate and especially perchlorate are highly explosive, in these cases ammonium is the reducing agent.

In an unusual process, ammonium ions form an amalgam. Such species are prepared by the electrolysis of an ammonium solution using a mercury cathode.[2] This amalgam eventually decomposes to release ammonia and hydrogen.[3]

Structure and bonding

The lone electron pair on the nitrogen atom (N) in ammonia, represented as a line above the N, forms the bond with a proton (H+). Thereafter, all four N–H bonds are equivalent, being polar covalent bonds. The ion has a tetrahedral structure and is isoelectronic with methane and borohydride. In terms of size, the ammonium cation (rionic = 175 pm) resembles the caesium cation (rionic = 183 pm).

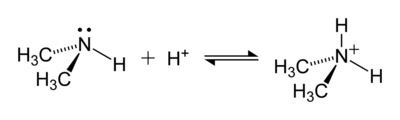

Organic ammonium ions

The hydrogen atoms in the ammonium ion can be substituted with an alkyl group or some other organic group to form a substituted ammonium ion (IUPAC nomenclature: aminium ion). Depending on the number of organic groups, the ammonium cation is called a primary, secondary, tertiary, or quaternary. With the exception of the quaternary ammonium cations, the organic ammonium cations are weak acids.

An example of a reaction forming an ammonium ion is that between dimethylamine, (CH3)2NH, and an acid, to give the dimethylaminium cation, (CH3)2NH+

2:

Quaternary ammonium cations have four organic groups attached to the nitrogen atom. They lack a hydrogen atom bonded to the nitrogen atom. These cations, such as the tetra-n-butylammonium cation, are sometimes used to replace sodium or potassium ions to increase the solubility of the associated anion in organic solvents. Primary, secondary, and tertiary ammonium salts serve the same function, but are less lipophilic. They are also used as phase-transfer catalysts and surfactants.

An unusual class or organic ammonium salts are derivatives of amine radical cations, R3N+. One example is tris(4-bromophenyl)ammonium hexachloroantimonate

Biology

Ammonium ions are a waste product of the metabolism of animals. In fish and aquatic invertebrates, it is excreted directly into the water. In mammals, sharks, and amphibians, it is converted in the urea cycle to urea, because urea is less toxic and can be stored more efficiently. In birds, reptiles, and terrestrial snails, metabolic ammonium is converted into uric acid, which is solid and can therefore be excreted with minimal water loss.[4]

Ammonium is an important source of nitrogen for many plant species, especially those growing on hypoxic soils. However, it is also toxic to most crop species and is rarely applied as a sole nitrogen source.[5]

Ammonium metal

The ammonium ion has very similar properties to the heavier alkali metals and is often considered a close relative.[6][7][8] Ammonium is expected to behave as a metal (NH+

4 ions in a sea of electrons) at very high pressures, such as inside gas giant planets such as Uranus and Neptune.[7][8]

Under normal conditions, ammonium does not exist as a pure metal, but does as an amalgam (alloy with mercury).[9]

See also

References

- ↑ In the substitutive nomenclature, NH+

4 is denoted by the name "azanium". - ↑ Pseudo-binary compounds

- ↑ "Ammonium Salts". VIAS Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Campbell, Neil A.; Jane B. Reece (2002). "44". Biology (6th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 937–938. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5.

- ↑ Britto, DT; Kronzucker, HJ (2002). "NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: a critical review" (PDF). Journal of Plant Physiology. 159 (6): 567–584. doi:10.1078/0176-1617-0774.

- ↑ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001), Inorganic Chemistry, San Diego: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- 1 2 Stevenson, D. J. (November 20, 1975). "Does metallic ammonium exist?". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 258: 222–223. Bibcode:1975Natur.258..222S. doi:10.1038/258222a0. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- 1 2 Bernal, M. J. M.; Massey, H. S. W. (February 3, 1954). "Metallic Ammonium" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Wiley-Blackwell for the Royal Astronomical Society. 114: 172–179. Bibcode:1954MNRAS.114..172B. doi:10.1093/mnras/114.2.172. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Reedy, J.H. (October 1, 1929). "Lecture demonstration of ammonium amalgam". Journal of Chemical Education. 6 (10): 1767. doi:10.1021/ed006p1767. Retrieved October 28, 2015.