American Horse (elder)

.jpg)

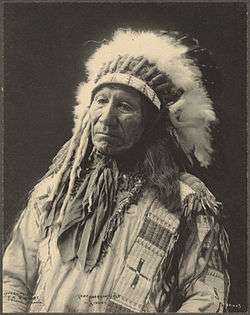

American Horse (Oglala Lakota: Wašíčuŋ Tȟašúŋke in Standard Lakota Orthography)(a/k/a "American Horse the Elder") (1830–September 9, 1876) was an Oglala Lakota warrior chief renowned for Spartan courage and honor. American Horse is notable in American history as one of the principal war chiefs allied with Crazy Horse during Red Cloud's War (1866–1868) and the Battle of the Little Bighorn during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. Chief American Horse was a son of Old Chief Smoke, an Oglala Lakota head chief and one of the last great Shirt Wearers, a highly prestigious Lakota warrior society. He was a signatory to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, along with his brothers Chief Red Cloud and Chief Blue Horse. A month or so after the Treaty, American Horse was chosen a "Ogle Tanka Un" (Shirt Wearer, or war leader) along with Crazy Horse, Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses and Man That Owns a Sword. On September 9, 1876, American Horse was mortally wounded in the Battle of Slim Buttes fighting to protect his family and defending against the white invasion of the “Paha Sapa“ Black Hills.

The Smoke People

Chief American Horse was a son of Old Chief Smoke. Old Chief Smoke was an Oglala Lakota head chief and one of the last great Shirt Wearers, a highly prestigious Lakota warrior society. The Smoke People were one of the most prominent Lakota families of the 18th and 19th centuries. Old Chief Smoke was one of the first Lakota chiefs to appreciate the power of the whites, their overwhelming numbers and the futility of war. He appreciated the need for association and learned the customs of the whites. Old Chief Smoke had five wives who bore him many children.[1] Old Chief Smoke’s sons carried the Smoke People legacy of leadership in Oglala Lakota culture into the early 20th century. The children of Old Chief Smoke were Spotted Horse Woman, Chief Big Mouth (1822-1869), Chief Blue Horse (1822-1908), Chief Red Cloud (1822-1909), Chief American Horse (1830-1876), Chief Bull Bear III, Chief Solomon Smoke II, Chief No Neck and Woman Dress (1846-1920).[2]

Treaty of Ft. Laramie 1868

Chief American Horse was one of the principal war chiefs allied with Crazy Horse and Red Cloud during Red Cloud's War (1866-1868). American Horse was a signatory to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, along with Chief Red Cloud and Chief Blue Horse, his brothers.[3] The treaty was an agreement between the United States and the Lakota Nation guaranteeing the Lakota ownership of the Black Hills “Paha Sapa“ and land and hunting rights in South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana. The Powder River Country was to be henceforth closed to all whites. The Treaty ended Red Cloud's War. A month or so after the Treaty of 1868, four "Ogle Tanka Un" (Shirt Wearers, or war leaders) were chosen: Crazy Horse, American Horse, Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses and Man That Owns a Sword.[4]

Crook’s Horsemeat March

Crook’s "Horsemeat March” marked the beginning of one of the most grueling marches in American military history. Crook’s command consisted of about 2,200 men: 1,500 cavalry, 450 infantry, 240 Indian scouts, and a contingent of civilian employees, including 44 white scouts and packers. Crook’s civilian scouts included Frank Grouard, Baptiste “Big Bat” Pourier, Baptiste “Little Bat” Garnier, Captain Jack Crawford and Charles “Buffalo Chips” White.[5] News of the defeat of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25 and 26, 1876, arrived in the East as the U.S. was observing its centennial.[6] The American public was dismayed and called to punish the Sioux. On August 26, 1876, with his men rationed for fifteen days, a determined General Crook departed from the Powder River and headed east toward the Little Missouri pursuing the Indians. Crook feared that Indians would scatter to seek game rather than meet the soldiers in combat after the fight with Custer. All other commanders had withdrawn from pursuit, but Crook resolved to teach the Indians a lesson. He meant to show that neither distance, bad weather, the loss of horses nor the absence of rations could deter the U.S. Army from following its enemies to the bitter end.[7] War correspondents with national newspapers fought alongside General Crook and reported the campaign by telegraph. Correspondents embedded with Crook were Robert Edmund Strahorn for the New York Times, Chicago Tribune and the Rocky Mountain News; John F. Finerty for the Chicago Times; Reuben Briggs Davenport for New York Herald and Joe Wasson for the New York Tribune and Alta California (San Francisco).[8]

Chief American Horse at Slim Buttes

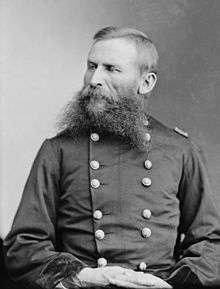

The Battle of Slim Buttes was fought on September 9 and 10, 1876, in the Great Sioux Reservation between the United States Army and the Sioux. The Battle of Slim Buttes was the first U.S. Army victory after Custer’s defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25 and 26, 1876, in the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. Brigadier General George R. Crook, one of the U.S. Army’s ablest Indian fighters led the “Horsemeat March”, one of the most grueling military expeditions in American history destroying Oglala Chief American Horse’s village at Slim Buttes and repelling a counter-attack by Crazy Horse. The American public was fixed on news of the defeat of General George Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn; and war correspondents with national newspapers fought alongside General Crook and reported the events. The Battle of Slim Buttes signaled a series of punitive blows that ultimately broke Sioux armed resistance to reservation captivity and forced their loss of the Black Hills “Paha Sapa“.[9]

The Village

Following the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Lakota leaders split up, each doing what they thought best for their people. Most were heading back to the reservations. On September 9, 1876, Chief American Horse’s camp of 37 lodges, about 260 people, of whom 30 to 40 were warriors, was attacked and destroyed by General George Crook at the Battle of Slim Buttes.[10] Chief American Horse’s camp was a rich prize. “It was the season when the wild plums ripen. All the agency Sioux were drifting back to the agencies with their packs full of dried meet, buffalo tongues, fresh and dried buffalo berries, wild cherries, plums and all the staples and dainties which tickled the Indian palate.” [11] The lodges were full of furs and meat, and it seemed to be a very rich village. Crook destroyed food, seized three or four hundred ponies, arms and ammunition, furs and blankets.[12] In a dispatch written for the Omaha Daily Bee, Captain Jack Crawford described the cornucopia he encountered: “Tepees full of dried meats, skins, bead work, and all that an Indian’s head could wish for.” [13] Of significance, troopers recovered items from the Battle of Little Bighorn, including a 7th Cavalry Regiment guidon from Company I, fastened to the lodge of Chief American Horse, and the bloody gauntlets of slain Captain Myles Keogh.[14] “One of the largest of the lodges, called by Grouard the “Brave Night Hearts,” supposedly occupied by the guard, contained thirty saddles and equipment. One man found eleven thousand dollars in one of the tipis. Others found three 7th Cavalry horses; letters written to and by 7th Cavalry personnel; officers’ clothing; a large amount of cash; jewelry; government-issued guns and ammunition." [15]

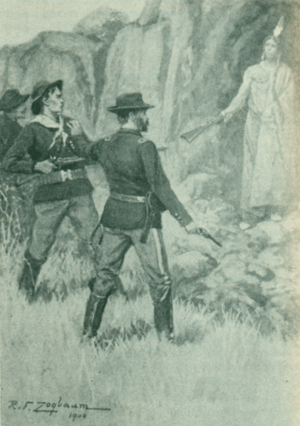

Chief American Horse’s Defiance

On September 9, 1876, Chief American Horse's village at Slim Buttes was assaulted in a dawn attack by Captain Anson Mills and 150 troopers. At the onset of a stampede of Indian ponies and cavalry charge, Chief American Horse with his family of three warriors and about twenty-five women and children retreated into one of the ravines that crisscrossed the village amongst the tipis. The winding dry gully was nearly 20 feet deep and ran some 200 yards back into a hillside. Trees and brush obstructed the view of the interior. “We found that some of the Indians had got into a cave at one side of the village. One of the men started to go past that spot on the hill, and as he passed the place he and his horse were both shot. This cave or dugout was down in the bed of a dry creek. The Indian children had been playing there, and dug quite a hole in the bank, so that it made more of a cave than anything else, large enough to hold a number of people.” [16] Troopers were alerted about the ravine when Private John Wenzel, Company A, Third Cavalry, became the first army fatality at Slim Buttes when he ill-advisedly approached the ravine from the front and a Sioux bullet slammed into his forehead. Wenzel’s horse was also shot and killed. An attempt was made to dislodge the Indians and several troopers were wounded.[17] “Grouard and Big Bat Pourier crept close enough to the banks of the ravine to parley with the concealed Indians in endeavors to get them to surrender. But the savages were so confident of succor from Crazy Horse and his much larger force, who were encamped only a dozen miles to the west, and to whom they had sent runners early in the morning, that they were defiant to the last.” The Souix felt no urgent need to surrender, for they defiantly yelled over to the soldiers that more Sioux camps were at hand and their warriors would soon come to free them. Chief American Horse, anticipating relief from other villages, constructed a dirt breastworks in front of the cave and geared for a stout defense.[18]

General Crook at the Ravine

On September 9, 1876, General Crook’s relief column endured a forced march of twenty-miles to Slim Buttes in about four hours and a half hours arriving at 11:30 a.m. The whole cheering command entered the valley, and the village teemed with activity like an anthill which had just been stirred up.[19] Crook immediately established his headquarters and set up a field hospital in one of the Indian lodges.[20] Crook inventoried the camp and the booty. The camp held thirty-seven lodges. A three- or four-year-old girl was discovered, but no bodies were found. Over 5,000 pounds of dried meat was found and was a “God-send” for the starved troopers.[21] Troopers separated the stores to be saved from the greater number to be destroyed, and the remaining tipis were pulled down. General Crook then turned his full attention to Chief American Horse and his family in the ravine.

“Crook, exasperated by the protracted defense of the hidden Sioux, and annoyed at the casualties inflicted among his men, formed a perfect cordon of infantry and dismounted cavalry around the Indian den. The soldiers opened upon it an incessant fire, which made the surrounding hills echo back a terrible music.” [23] “The circumvalleted Indians distributed their shots liberally among the crowding soldiers, but the shower of close-range bullets from the later terrified the unhappy squaws, and they began singing the awful Indian death chant. The papooses wailed so loudly, and so piteously, that even not firing could not quell their voices. General Crook ordered the men to suspend operations immediately, but dozens of angry soldiers surged forward and had to be beat back by officers.[23] “Neither General Crook nor any of his officers or men suspected that any women and children were in the gully until their cries were heard above the volume of fire poured upon the fatal spot.” [24] Grouard and Pourier, who spoke Lakota, were ordered by General Crook to offer the women and children quarter. This was accepted by the besieged, and Crook in person went into the mouth of the ravine and handed out one tall, fine looking woman, who had an infant strapped to her back. She trembled all over and refused to liberate the General’s hand. Eleven other squaws and six papooses were taken out and crowded around Crook, but the few surviving warriors refused to surrender and savagely re-commenced the fight.[23]

"Rain of Hell"

Chief American Horse refused to leave, and with three warriors, five women and an infant, remained in the cave. Exasperated by the increasing casualties in his ranks, Crook directed some of his infantry and dismounted cavalry to form across the opening of the gorge. On command, the troopers opened steady and withering fire on the ravine which sent an estimated 3,000 bullets among the warriors.[25] Finerty reported, “Then our troops reopened with a very ‘rain of hell’ upon the infatuated braves, who, nevertheless, fought it out with Spartan courage, against such desperate odds, for nearly two hours. “Such matchless bravery electrified even our enraged soldiers into a spirit of chivalry, and General Crook, recognizing the fact that the unfortunate savages had fought like fiends, in defense of wives and children, ordered another suspension of hostilities and called upon the dusky heroes to surrender.” [26] Strahorn recalled the horror of the ravine at Slim Buttes. “The yelling of Indians, discharge of guns, cursing of soldiers, crying of children, barking of dogs, the dead crowded in the bottom of the gory, slimy ditch, and the shrieks of the wounded, presented the most agonizing scene that clings in my memory of Sioux warfare.” [27]

Surrender of Chief American Horse

When matters quieted down, Frank Grouard and Baptiste “Big Bat” Pourier asked American Horse again if they would come out of the hole before any more were shot, telling them they would be safe if they surrendered. “After a few minutes deliberation, the chief, American Horse, a fine looking, broad-chested Sioux, with a handsome face and a neck like a bull, showed himself at the mouth of the cave, presenting the butt end of his rifle toward the General.[26] He had just been shot in the abdomen, and said in his native language, that he would yield if the lives of the warriors who fought with him were spared.[26] Chief American Horse had been shot through the bowels and was holding his entrails in his hands as he came out and presented the butt end of his rifle to General Crook. Pourier recalled that he first saw American Horse kneeling with a gun in his hand, in a hole on the side of the ravine that he had scooped out with a butcher knife. Chief American Horse had been shot through the bowels and was holding his entrails in his hands as he came out. Two of the squaws were also wounded. Eleven were killed in the hole.[28] Grouard recognized Chief American Horse, “but you would not have thought he was shot from his appearance and his looks, except for the paleness of his face. He came marching out of that death trap as straight as an arrow. Holding out one of his blood-stained hands he shook hands with me.” [29] When Chief American Horse presented the butt end of his rifle, General Crook, who took the proffered rifle, instructed Grouard to ask his name. The Indian replied in Lakota, “American Horse.” [25] Some of the soldiers who lost their comrades in the skirmish shouted, “No quarter!’, but not a man was base enough to attempt shooting down the disabled chief.[26] Crook hesitated for a minute and then said,‘Two or three Sioux, more or less, can make no difference. I can yet use them to good advantage. "Tell the chief,“ he said turning to Grouard, "that neither he nor his young men will be harmed further.” [26] “This message having been interpreted to Chief American Horse, he beckoned to his surviving followers, and two strapping Indians, with their long, but quick and graceful stride, followed him out of the gully. The chieftain’s intestines protruded from his wound, but a squaw, his wife perhaps, tied her shawl around the injured part, and then the poor, fearless savage, never uttering a complaint, walked slowly to a little camp fire, occupied by his people about 20 yards away, and sat down among the women and children.” [26]

Crazy Horse Attacks

Crazy Horse attempted to rescue American Horse and his family. Indians who escaped Mills’ early morning assault spread the word to nearby Lakota and Cheyenne camps, and informed Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and other leaders they were attacked by 100-150 soldiers. Crazy Horse immediately assembled 600-800 warriors and rode about ten miles northward to rescue Chief American Horse and recover ponies and supplies.[30] During the afternoon Chief American Horse and some of the squaws informed Gen. Crook, through the scouts, that Crazy Horse was not far off, and that we would certainly be attacked before nightfall.[31] “In anticipation of that afternoon tea party which was promised to be given by Crazy Horse, Crook deployed his forces to give that chieftain the surprise of his life. Concealing the major portion in the ravine in up-to-the-minute readiness and eagerness for an attack, he deployed just enough of the boys in plain sight to carry out the impression, which the Indian couriers had conveyed to Crazy Horse, that only about a hundred soldiers would be found to oppose his eager and confident large reinforcements.” [32] As a grave was being dug for Private Wenzel, and the starved troopers were ready to dine on captured bison meat, rifle shots were heard from the bluffs above and around the camp.[33] Crook immediately ordered the village to be burned. “Then followed the most spectacular and tragically gripping and gratifying drama of the whole Sioux War, enacted with a setting and view for those of us in the ambushing corps that could not be improved upon. The huge amphitheater, leading from our position in the front orchestra row, up over a gradually rising terrain to the rim of the hills which surrounded on three sides, was not unlike the situation which Crazy Horse had chosen for his Battle of the Rosebud.” [34] Finerty tells how the Indians attacked. “Like the Napoleonic cuirassiers at Waterloo, they rode along the line looking for a gap to penetrate. They kept up perpetual motion encouraged by a warrior, doubtless Crazy Horse himself, who, mounted on a fleet, white horse, galloped around the array and seemed to possess the power of ubiquity.” [35] Strahorn reported, “Suddenly the summits seemed alive with an eager, expectant and gloating host of savages who dashed over and down the slope, whooping and recklessly firing at every jump.” [34]

Crazy Horse was surprised to find American Horse’s village massed with Crook's main column of over 2,000 infantry, artillery, cavalry and scouts.[36] “Crazy Horse so little dreamed of the heavy reinforcements of Captain Mills’ small band that, in the utmost confidence of ‘eating us alive’ he launched his followers right down upon the front and flanks of our splendid defensive position. They were permitted to approach with blood curdling whoops and in a savage array within easy and sure-fire rifle range before the order to fire was given. They reacted to the deadly shock in a manner that was the real beginning of the end of the Sioux War, so far as any major performance of Crazy Horse was concerned. Bewildered and demoralized by the well-aimed volleys of our two-thousand guns, they dashed for cover in every direction, closely followed by details of our boys who were allotted that much-sought privilege.” [37] “Failing to break into that formidable circle, the Indians, after firing several volleys, their original order of battle being completely broken, and recognizing the folly of fighting such an outnumbering force any longer, glided away from our front with all possible speed. As the shadows came down into the valley, the last shots were fired and the affair at Slim Buttes was over.” [38]

Casualties

Captain Mills reported the assault: “It is usual for commanding officers to call special attention to acts of distinguished courage, and I trust the extraordinary circumstances of calling on 125 men to attack, in the darkness, and in the wilderness, and on the heels of the late appalling disasters to their comrades, a village of unknown strength, and in the gallant manner in which they executed everything requited of them to my entire satisfaction.” [39] U.S. Army casualties were relatively light with a loss of 30 men: 3 killed, 27 wounded, some seriously.[40] Because the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors maintained a distance of five to eight hundred yards, and consistently fired their weapons high, casualties were few.[41] Those who died in the field were Private John Wenzel, Private Edward Kennedy and Scout Charles “Buffalo Chips” White.” [42] Private Kennedy, Company C, Fifth Cavalry, had half the calf of his leg blown away in a barrage, and throughout the night medical personnel labored to save his life. Private Kennedy and Chief American Horse died in the surgeons’ lodge that evening.[43] Lt. Von Luettwitz had his shattered leg amputated above the knee and Private John M. Stevenson of Company I, Second Cavalry, received a severe ankle wound at the ravine. “The Indians must have lost quite heavily. Several of their ponies, bridled but riderless, were captured during the evening. Indians never abandon their war ponies, unless they happen to be surprised or killed. Pools of blood were found on the ledges of the bluffs, indicating where Crazy Horse’s warriors paid the penalty of their valor with their lives.” [44] Reports of Indian casualties varied, and many bodies were carried away. Sioux confirmed casualties were at least 10 dead, and an unknown number wounded. About 30 Sioux men, women and children were in the ravine with Chief American Horse when the firefight began, and 20 women and children surrendered to Crook.[45] Ten individuals remained in the ravine during the “Rain of Hell” and five were killed; Iron Shield, three women, one infant and Chief American Horse who died that evening. The rest were made prisoners.[46] Charging Bear resisted most desperately and was finally dragged out of his lair at the bottom of the deep gully with only one cartridge left. Taken prisoner, he soon after enlisted with General Crook, exhibiting great prowess and bravery on behalf of his new leader and against his former comrades.” [47]

Death of American Horse

Chief American Horse was examined by the two surgeons. One of them pulled the chief’s hands away, and the intestines dropped out. “Tell him he will die before next morning,” said the surgeon.[48] The surgeons worked futilely to close his stomach wound, and Chief American Horse refused morphine preferring to clench a stick between his teeth to hide any sign of pain or emotions and thus he bravely and stolidly died.[27] Chief American Horse lingered until 6:00 a.m. and confirmed that the tribes were scattering and were becoming discouraged by war. “He appeared satisfied that the lives of his squaws and children were spared.” [49] Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy, who attended the dying chief, said that he was cheerful to the last and manifested the utmost affection for his wives and children. American Horse’s squaws and children were allowed to remain on the battleground after the dusky hero’s death, and subsequently fell into the hands of their own people. Even “Ute John” respected the cold clay of the brave Sioux leader, and his corpse was not subjected to the scalping process.” [50] Crook was most gentle in his assurances to all of them that no further harm should come if they went along peacefully, and it only required a day or two of kind treatment to make them feel very much at home.[27]

Two American Horses

There are two Oglala Lakota chiefs named American Horse notable in American history. Historian George E. Hyde distinguished them by referring to “Chief American Horse the Elder” as the son of Old Chief Smoke and the cousin of Red Cloud, and “Chief American Horse the Younger” as the son of Sitting Bear, and son-in-law to Red Cloud.[51] American Horse the Younger (1840 – December 16, 1908) was an Oglala Lakota chief, statesman, educator and historian. American Horse the Younger is notable in American history as a U.S. Army Indian Scout and a progressive Oglala Lakota leader who promoted friendly associations with whites and education for his people. American Horse the Younger opposed Crazy Horse during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877 and the Ghost Dance Movement of 1890, and was a Lakota delegate to Washington. American Horse the Younger was one of the first Wild Westers with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and a supporter of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. “His record as a councillor of his people and his policy in the new situation that confronted them was manly and consistent and he was known for his eloquence." American Horse the Younger gained influence during the turbulence of the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. After news of the death of Chief American Horse the Elder at the Battle of Slim Buttes, Manishnee (Can not walk, or Played out)” seized an opportunity and assumed the name “American Horse.” [52] American Horse the Younger was not related to American Horse the Elder, son of Old Chief Smoke. He was the son of Sitting Bear, leader of the True Oglalas, a band of Oglala opposed to the Smoke people [53] The identities and accounts of American Horse the Elder and the American Horse the Younger have been blended by some historians. Like his great friend Crazy Horse, there are no known photographs or drawings of Chief American Horse the Elder.[54] “The Oglalas seem incapable of clearing up the tangle.” [55]

References

- ↑ Old Chief Smoke's five wives were Looking Cloud Woman of the Teton Mnikȟówožu, Comes Out Slow Woman of the Teton Oglála, Burnt Her Woman of the Teton Sičháŋǧu, Yellow Haired Woman of the Southern Cheyenne, and Brown Eyes Woman of the Teton Húŋkpapȟa.

- ↑ Red Cloud was adopted by Old Chief Smoke, his maternal uncle, around 1825 at the age of three after Red Cloud’s parents died. Blue Horse and Red Cloud were raised as brothers and mentored by Old Chief Smoke.

- ↑ http://www.aics.org/WK/treaty1868.html

- ↑ Edward Kadlecek and Mabell Kadlecek, “To Kill an Eagle: Indian Views on the Last Days of Crazy Horse,” (1981), p. 14. Shirt Wearers occupied a position of considerable responsibility. They selected promising hunting areas, settled personal conflicts and set tribal policy in important matters such as treaties and land use. Edward J. Reilly, “Legends of American Indian Resistance,” (2011), p.155.

- ↑ Jerome A. Greene, “Slim Buttes, 1876: An Episode of the Great Sioux War”, (hereinafter “Greene”) (1982), p.33.

- ↑ Lynne V. Cheney, "1876: The Eagle Screams", American Heritage 25:3, Apr. 1974.

- ↑ Greene, p. 26, 31, 114-115.

- ↑ Greene, p.15.

- ↑ Greene, p.xiii-xiv. Vestal p.184.

- ↑ The number of occupants, including warriors, is a matter of conjecture. Greene, p. 49, 159. John Frederick Finerty, "War-path and bivouac: The Conquest of the Sioux", (hereinafter "Finerty") (1890), p. 255.

- ↑ See Stanley Vestal, “Sitting Bull: Champion of the Sioux” (1932), p.184.

- ↑ “We took the horses along and they amounted to three or four hundred head.” DeBarthe, Joe (1958). "Frank Grouard's Story of the Battle". Life and Adventures of Frank Grouard", (hereinafter "Grouard") ,University of Oklahoma Press. p.307-311. The troopers also captured about 300 fine ponies to partly replace their dead horses. Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 203-204.

- ↑ Darlis A. Miller, “Captain Jack Crawford: Buckskin Poet, Scout and Showman,” (hereinafter “Buckskin Poet”) (1993), p. 60.

- ↑ “During the charge made on the village Private W. J. McClinton, of Troop C., Third cavalry, discovered one of the guidons belonging to the ill-fated Custer command. It was fastened to the lodge of American Horse.” Grouard, p. 306.

- ↑ Joe DeBarthe, “Life and Adventures of Frank Grouard”,(hereinafter "Grouard") (1894), p. 307. Greene, p.73.

- ↑ Grouard, p. 307.

- ↑ Greene, p.66. “Anson Mills”, p.430.

- ↑ Robert E. Strahorn, “Ninety Years of Boyhood”, (hereinafter cited as “Strahorn Autobiography”), Strahorn Memorial Library, College of Idaho, (1942), p.204.

- ↑ Anson Mills, “My Story,” (hereinafter “Anson Mills”)(1918), p.430. Finerty, p.70, 253. Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 203. Greene, p.71.

- ↑ Doctors deliberated amputating Lt. Von Luettwitz’s right leg.

- ↑ “Greene, p.72.

- ↑ “The fact is, Crook is nothing but an Indian...I mean that his mind, physiognomy and education are all Indian. Look at his face,...[the] high cheek bones [and] the contour of his skull; and his manners--stolid, separate, averse to talk. He can take his gun and cross then desert, subsisting on the way where you or i would starve. Perfectly self-reliant for any venture, delighted with lonely travel and personal hazard, carrying nothing but his arms, he will walk after a trial all day and night when night comes, no matter how cold, he wraps himself in an Indian blanket, humped up in Indian fashion, and pitches himself into a sage brush, there to be perfectly easy till morning. He will follow an antelope for three days. He requires nothing to drink or smoke, and very little to eat. Abstemious, singular [sic] utterly ignorant of fear, and yet stealthy as a cat, shy of women and strangers; and when he was a cadet he had all the same traits.” Greene, p. 17, citing Inyo Independent (Independence, Calf.), September 2, 1871. “In spite of previous broken treaties, many Lakota trusted and respected Crook. While he had been an adversary in the field of combat, he had also been a man of honor. A majority listened when the general told them, It is certain you will never get any better terms than offered in this bill, and the chances are you will not get so good. He at least never lied to us.” William S.E. Coleman, “Voices of Wounded Knee,”(2000), p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Finerty, p.254.

- ↑ Finerty, p.257

- 1 2 Greene, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Finerty, p.255.

- 1 2 3 Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 204.

- ↑ Greene, p.168. Grouard, p. 311.

- ↑ Grouard, p. 310-311.

- ↑ “I have heard the number of Sioux variously estimated, but I cannot presume to verify any of the estimates made. There could not, in my opinion, have been more than six to eight hundred of their fighting men opposed to us.” Finerty, p.264.

- ↑ Finerty, p.259.

- ↑ Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 204-205.

- ↑ Finerty, p.260, Greene, p.81.

- 1 2 Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 205.

- ↑ Finerty, p.263. Vestal, p.187.

- ↑ “The Indians had made their charge with the expectation of finding only a small body of troops, as had been reported to them by the Indians who had escaped from the village. I could tell pretty well from the way they charged down from all directions at once that they never expected to find such a large body of troops, and it gave them quite a surprise to find we were ready for them. It was not more than ten minutes before the fight became general all around the camp.” Grouard, p. 308.

- ↑ Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 205. Strahorn described the encounter: “The field could not have been more advantageous for foes, at is speedily occupied rock-covered bluffs commanded all approaches. Yet the one hour’s fight that followed was little more than a beautiful; and impressive skirmish drill for our troops, and a very ungraceful flight from all positions by the savages.” Greene, p. 87.

- ↑ Finerty, p.263.

- ↑ “Anson Mills”, p.431.

- ↑ Finerty, p. 263

- ↑ Only one soldier was wounded in the advance. Likewise the troops caused little harm to the Indians and found only one casualty. “The evening fight at Slim Buttes was not particularly sanguinary, as regarded our side, but it was the prettiest battle scene, so acknowledged to have been seen by men who had witnesses a hundred fights, that ever an Indian war correspondent was called upon to describe.” Finerty, p.261.

- ↑ Finerty, p. 263.

- ↑ Greene, p. 90.

- ↑ Finerty, p. 263

- ↑ Finerty, p. 263. “We secured only seven captives, two buck, four squaws and one little girl.” Grouard, p. 311.

- ↑ Greene, p.80.

- ↑ Later served as a corporal in Crook’s company of Indian Scouts. Greene, p.168, citing Bourke, “Diary,” p.877-78. Strahorn, Autobiography, p. 226.

- ↑ Finerty, p.255-256.

- ↑ Chicago Times, September 17, 1876.

- ↑ Finerty, p.265.

- ↑ George Hyde, Red Cloud's Folk: A History of the Oglala Sioux Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1937), p. 18.

- ↑ “American Horse liked notoriety and excitement and always seized an opportunity to leap into the center of the arena.” Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa), “Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains”, (hereinafter “Eastman”)(1919), p. 166.

- ↑ Eastman, p. 173.

- ↑ American Horse the Younger told Eastman that he succeeded to the name and position of his uncle American Horse the Elder who was killed at Sim Buttes in 1876. Eastman, p. 173.

- ↑ George E. Hyde, “Red Cloud's Folk: A History of the Oglala Sioux Indians”, (hereinafter “Hyde”)(1984). pp. 318.