Actaea racemosa

| Actaea racemosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Genus: | Actaea |

| Species: | A. racemosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Actaea racemosa L. | |

Actaea racemosa (black cohosh, black bugbane, black snakeroot, fairy candle; syn. Cimicifuga racemosa) is a species of flowering plant of the family Ranunculaceae. It is native to eastern North America from the extreme south of Ontario to central Georgia, and west to Missouri and Arkansas. It grows in a variety of woodland habitats, and is often found in small woodland openings. The roots and rhizomes have long been used medicinally by Native Americans. Extracts from these plant materials are thought to possess analgesic, sedative, and anti-inflammatory properties.

Today, black cohosh extracts are being studied as effective treatments for symptoms associated with menopause.[1]

Description

Black cohosh is a smooth (glabrous) herbaceous perennial plant that produces large, compound leaves from an underground rhizome, reaching a height of 25–60 cm (9.8–23.6 in).[2][3] The basal leaves are up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long and broad, forming repeated sets of three leaflets (tripinnately compound) having a coarsely toothed (serrated) margin. The flowers are produced in late spring and early summer on a tall stem, 75–250 cm (30–98 in) tall, forming racemes up to 50 cm (20 in) long. The flowers have no petals or sepals, and consist of tight clusters of 55-110 white, 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) long stamens surrounding a white stigma. The flowers have a distinctly sweet, fetid smell that attracts flies, gnats, and beetles.[2] The fruit is a dry follicle 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) long, with one carpel, containing several seeds.[4]

Taxonomy

The plant species has a history of taxonomic uncertainty dating back to Carl Linnaeus, who — on the basis of morphological characteristics of the inflorescence and seeds — had placed the species into the genus Actaea. This designation was later revised by Thomas Nuttall reclassifying the species to the genus Cimicifuga. Nuttall's classification was based solely on the dry follicles produced by black cohosh, which are typical of species in Cimicifuga.[4] However, recent data from morphological and gene phylogeny analyses demonstrate that black cohosh is more closely related to species of the genus Actaea than to other Cimicifuga species. This has prompted the revision to Actaea racemosa as originally proposed by Linnaeus.[4] Blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), despite its similar common name belongs to another family, the Berberidaceae, and is therefore not closely related to black cohosh.

Cultivation

A. racemosa grows in dependably moist, fairly heavy soil. It bears tall tapering racemes of white midsummer flowers on wiry black-purple stems, whose mildly unpleasant, medicinal smell at close range gives it the common name "Bugbane". The drying seed heads stay handsome in the garden for many weeks. Its deeply cut leaves, burgundy colored in the variety "atropurpurea", add interest to gardens, wherever summer heat and drought do not make it die back, which make it a popular garden perennial. It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[5]

Medicinal uses

Historical use

Native Americans used black cohosh to treat gynecological and other disorders, including sore throats, kidney problems, and depression.[3] Following the arrival of European settlers in the U.S. who continued the medicinal usage of black cohosh, the plant appeared in the U.S. Pharmacopoeia in 1830 under the name “black snakeroot”. In 1844 A. racemosa gained popularity when John King, an eclectic physician, used it to treat rheumatism and nervous disorders. Other eclectic physicians of the mid-nineteenth century used black cohosh for a variety of maladies, including endometritis, amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, sterility, severe after-birth pains, and for increased breast milk production.[6]

Contemporary use

Black cohosh is used today mainly as a dietary supplement marketed to women as remedies for the symptoms of premenstrual tension, menopause and other gynecological problems.[3] Recent meta-analysis of contemporary evidence supports these claims,[1] although the Cochrane Collaboration has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support its use for menopausal symptoms.[7] Study design and dosage of black cohosh preparations play a role in clinical outcome,[8] and recent investigations with pure compounds found in black cohosh have identified some beneficial effects of these compounds on physiological pathways underlying age-related disorders like osteoporosis.[9]

Side effects

According to Cancer Research UK: "Doctors are worried that using black cohosh long term may cause thickening of the womb lining. This could lead to an increased risk of womb cancer." They also caution that people with liver problems should not take it as it can damage the liver,[10] although a 2011 meta-analysis of research evidence suggested this concern may be unfounded.[11]

Studies on human subjects who were administered two commercially available black cohosh preparations did not detect estrogenic effects on the breast.[12]

No studies exist on long-term safety of black cohosh use in humans.[13] In a transgenic mouse model of cancer, black cohosh did not increase incidence of primary breast cancer, but increased metastasis of pre-existing breast cancer to the lungs.[14]

Liver damage has been reported in a few individuals using black cohosh,[3] but many women have taken the herb without reporting adverse health effects,[15] and a meta-analysis of several well-controlled clinical trials found no evidence that black cohosh preparations have any adverse effect on liver function.[11] Although evidence for a link between black cohosh and liver damage is not conclusive, Australia has added a warning to the label of all black cohosh-containing products, stating that it may cause harm to the liver in some individuals and should not be used without medical supervision.[16] Other studies conclude that liver damage from use of black cohosh is unlikely,[17] and that the main concern over its safe use is lack of proper authentication of plant materials and adulteration of commercial preparations with other plant species.[18]

Reported direct side-effects also include dizziness, headaches, and seizures; diarrhea; nausea and vomiting; sweating; constipation; low blood pressure and slow heartbeats; and weight problems.[19]

Because the vast majority of black cohosh materials are harvested from plants growing in the wild,[3] a recurring concern regarding the safety of black cohosh-containing dietary supplements is mis-identification of plants causing unintentional mixing-in (adulteration) of potentially harmful materials from other plant sources.[3]

Black Cohosh can interact with estrogens, progestins and birth control pills, as well as fertility treatments.[20]

Bioactive compounds

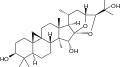

Like most plants, black cohosh tissues and organs contain many organic compounds with biological activity.[8][21][22] Estrogen-like compounds had originally been implicated in effects of black cohosh extracts on vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women.[23] Several other studies, however, have indicated absence of estrogenic effects[12][24] and compounds[22][25][26] in black cohosh-containing materials. Recent findings suggest that some of the clinically relevant physiological effects of black cohosh may be due to compounds that bind and activate serotonin receptors,[27] and a derivative of serotonin with high affinity to serotonin receptors, Nω-methylserotonin, has been identified in black cohosh.[28] Complex biological molecules, such as triterpene glycosides (e.g. cycloartanes), have been shown to reduce cytokine-induced bone loss (osteoporosis) by blocking osteoclastogenesis in in vitro and in vivo models.[9] 23-O-acetylshengmanol-3-O-β-d-xylopyranoside, a cycloartane glycoside from Actaea racemosa, has been identified as a novel efficacious modulator of GABAA receptors with sedative activity in mice [29]

See also

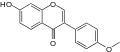

Chemical constituents

-

Formononetin a constituent of Cimicifuga racemosa (Black Cohosh)[1]

- ^ a b Murray, edited by Joseph E. Pizzorno, Jr., Michael T. (2012). Textbook of natural medicine (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 661. ISBN 9781437723335.

References

- 1 2 Beer, A.-M.; A. Neff (August 2013). "Differentiated Evaluation of Extract-Specific Evidence on Cimicifuga racemosa's Efficacy and Safety for Climacteric Complaints". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 1.722: 860602. doi:10.1155/2013/860602. PMC 3767045

. PMID 24062793.

. PMID 24062793. - 1 2 Richo Cech (2002). Growing at-risk medicinal herbs. Horizon Herbs. pp. 10–27. ISBN 0-9700312-1-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Predny ML, De Angelis P, Chamberlain JL (2006). Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa): An annotated Bibliography. General Technical Report SRS–97. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station. p. 99. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- 1 2 3 Compton JA, Culham A, Jury SL (1998). "Reclassification of Actaea to include Cimicifuga and Souliea (Ranunculaceae): Phylogeny inferred from morphology, nrDNA ITS, and epDNA trnL-F sequence variation". Taxon. 47 (3): 593–634. doi:10.2307/1223580. JSTOR 1223580.

- ↑ "Actaea racemosa". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ Anon (August 2003). "Cimicifuga racemosa". Alternative Medicine Review. 8 (2): 186–89. PMID 12777164.

- ↑ Leach, MJ; Moore, V (12 September 2012). "Black cohosh (Cimicifuga spp.) for menopausal symptoms.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD007244. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007244.pub2. PMID 22972105.

- 1 2 Viereck V, Emons G, Wuttke W (2005). "Black cohosh: just another phytoestrogen?". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 16 (5): 214–221. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2005.05.002. PMID 15927480.

- 1 2 Qiu SX, Dan C, Ding LS, Peng S, Chen SN, Farnsworth NR, Nolta J, Gross ML, Zhou P (2007). "A triterpene glycoside from black cohosh that inhibits osteoclastogenesis by modulating RANKL and TNFα signaling pathways". Chemistry & Biology. 14 (7): 860–869. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.06.010. PMID 17656322.

- ↑ "Black Cohosh". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- 1 2 Naser, Belal; Schnitker, Jörg; Minkin, Mary Jane; De Arriba, Susana Garcia; Nolte, Klaus-Ulrich; Osmers, Rüdiger (2011). "Suspected black cohosh hepatotoxicity". Menopause. 18 (4): 366–75. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181fcb2a6. PMID 21228727.

- 1 2 Ruhlen RL, Haubner J, Tracy JK, Zhu W, Ehya H, Lamberson WR, Rottinghaus GE, Sauter ER (2007). "Black cohosh does not exert an estrogenic effect on the breast". Nutrition and Cancer. 59 (2): 269–277. doi:10.1080/01635580701506968. PMID 18001221.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers About Black Cohosh and the Symptoms of Menopause".

- ↑ Davis VL, Jayo MJ, Ho A, Kotlarczyk MP, Hardy ML, Foster WG, Hughes CL (2008). "Black cohosh increases metastatic mammary cancer in transgenic mice expressing c-erbB2". Cancer Research. 68 (20): 8377–8383. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1812. PMID 18922910.

- ↑ "Workshop on the Safety of Black Cohosh in Clinical Studies" (PDF).

- ↑ "Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration alert".

- ↑ Teschke R, Schmidt-Taenzer W, Wolff A (2011). "Spontaneous reports of assumed herbal hepatotoxicity by black cohosh: is the liver-unspecific Naranjo scale precise enough to ascertain causality?". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 20 (6): 567–82. doi:10.1002/pds.2127. PMID 21702069.

- ↑ Teschke R, Schmidt-Taenzer W, Wolff A (2011). "Herb induced liver injury presumably caused by black cohosh: a survey of initially purported cases and herbal quality specifications" (PDF). Annals of Hepatology. 10 (3): 249–59. PMID 21677326.

- ↑ "Black Cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa)".

- ↑ "Black cohosh pills ~ Black Cohosh". www.blackcohosh10.com. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- ↑ Nuntanakorn P, Jiang B, Yang H, Cervantes-Cervantes M, Kronenberg F, Kennelly EJ (2007). "Analysis of polyphenolic compounds and radical scavenging activity of four American Actaea species". Phytochem Anal. 18 (3): 219–28. doi:10.1002/pca.975. PMC 2981772

. PMID 17500365.

. PMID 17500365. - 1 2 Avula B, Wang YH, Smillie TJ, Khan IA (March 2009). "Quantitative determination of triterpenoids and formononetin in rhizomes of black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) and dietary supplements by using UPLC-UV/ELS detection and identification by UPLC-MS". Planta Med. 75 (4): 381–6. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1088384. PMID 19061153.

- ↑ Seidlova-Wuttke D, Hesse O, Jarry H, et al. (October 2003). "Evidence for selective estrogen receptor modulator activity in a black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) extract: comparison with estradiol-17beta". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 149 (4): 351–62. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1490351. PMID 14514351.

- ↑ Lupu R, Mehmi I, Atlas E, et al. (November 2003). "Black cohosh, a menopausal remedy, does not have estrogenic activity and does not promote breast cancer cell growth". Int. J. Oncol. 23 (5): 1407–12. doi:10.3892/ijo.23.5.1407. PMID 14532983.

- ↑ Jiang B, Kronenberg F, Balick MJ, Kennelly EJ (July 2006). "Analysis of formononetin from black cohosh (Actaea racemosa)". Phytomedicine. 13 (7): 477–86. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2005.06.007. PMID 16785040.

- ↑ Kennelly EJ, Baggett S, Nuntanakorn P, Ososki AL, Mori SA, Duke J, Coleton M, Kronenberg F (July 2002). "Analysis of thirteen populations of black cohosh for formononetin". Phytomedicine. 9 (5): 461–7. doi:10.1078/09447110260571733. PMID 12222669.

- ↑ Burdette JE, Liu J, Chen SN, Fabricant DS, Piersen CE, Barker EL, Pezzuto JM, Mesecar A, Van Breemen RB, Farnsworth NR, Bolton JL (2003). "Black cohosh acts as a mixed competitive ligand and partial agonist of the serotonin receptor". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (19): 5661–5670. doi:10.1021/jf034264r. PMID 12952416.

- ↑ Powell SL, Gödecke T, Nikolic D, Chen SN, Ahn S, Dietz B, Farnsworth NR, van Breemen RB, Lankin DC, Pauli GF, Bolton JL (2008). "In vitro serotonergic activity of black cohosh and identification of N(omega)-methylserotonin as a potential active constituent". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (24): 11718–11726. doi:10.1021/jf803298z. PMID 19049296.

- ↑ Strommer B, Khom S, Kastenberger I, Sezai Cicek S, Stuppner H, Schwarzer C, Hering S (August 2014). "A cycloartane glycoside derived from Actaea racemosa L. modulates GABAA receptors and induces pronounced sedation in mice.". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 351: 234–42. doi:10.1124/jpet.114.218024. PMID 25161170.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Actaea racemosa. |