Abraham Lincoln's patent

| No. 6,469 patent for "Buoying Vessels Over Shoals" | |

|---|---|

Patent Model of Abraham Lincoln's invention at Smithsonian Institution | |

| Creator | Abraham Lincoln |

| Filing date | March 10, 1849 |

| Issue date | May 22, 1849 |

| Location | Illinois |

Abraham Lincoln's patent is a patented invention to lift boats over shoals and obstructions in a river.[1] It is the only United States patent ever registered to a President of the United States.[2][3] Lincoln conceived the idea of inventing a mechanism that would lift a boat over shoals and obstructions when on two different occasions the boat on which he traveled got hung up on obstructions. Documentation of this patent was discovered in 1997.

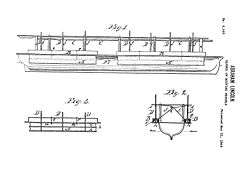

This device was composed of large bellows attached to the sides of a boat that was expandable due to air chambers. His successful patent application led to his drafting and delivering two lectures on the subject of patents while he was President. Lincoln was at times a patent attorney and was familiar with the patent application process as well as patent lawsuit proceedings. Among his notable patent law experiences was litigation over the mechanical reaper.

Background

The invention stemmed from Lincoln's experiences ferrying travelers and carrying freight on the Great Lakes and some midwestern rivers.[4] In 1860, Lincoln wrote his autobiography and recounted that while in his late teens he took a flatboat down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from his home in Indiana to New Orleans while employed as a hired hand. The son of the boat owner kept him company and the two went out on this new undertaking without any other helpers.[5]

After moving to Macon County, Illinois, Lincoln made an additional trip a few years later on another flatboat that went from Beardstown, Illinois, to New Orleans. He, John D. Johnston (his stepmother's son) and John Hanks were hired as laborers by Denton Offutt to take a flatboat to New Orleans. They were to join Offutt at Springfield, Illinois. In early March 1831, the boys purchased a large canoe and traveled south on the Sangamon River. When they finally found him, they discovered Offutt had failed to secure a contract for a freight trip in Beardstown. Thus, purchasing the large canoe was an unnecessary expense. They then tried to cut their losses and worked for Offutt for twelve dollars per month cutting timber and building a boat at the Old Sangamon town (fifteen miles northwest of Springfield) on the Sangamon River. The new boat carried them to New Orleans based upon the original contract with Offutt.[5]

As William Horman first wrote, "necessity is the mother of invention."[6] Before Offutt's flatboat could reach the Illinois River, it got hung up on a milldam at the Old Sangamon town. As the boat was sinking, Lincoln took action, unloading some cargo to right the boat, then drilling a hole in the bow with a large auger borrowed from the local cooperage. After the water drained, he replugged the hole. With local help, he then portaged the empty boat over the dam, and was able to complete the trip to New Orleans.[5]

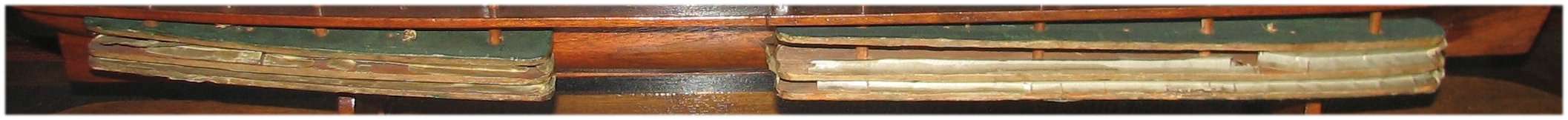

At the age of 23, Lincoln started his political career in New Salem. Near the top of his agenda was improvement of navigation on the Sangamon River. Lincoln's law partner and biographer, William H. Herndon, also reports an additional incident at the time: a boat Lincoln was on got stranded on a shoal; the boat gradually swung clear and was dislodged after much manual exertion.[5] This event, along with the Offutt's boat/milldam incident, prompted Lincoln to start thinking about how to lift vessels over river obstructions and shoals. He eventually came up with an idea for inflatable flotation.Patent 6469 was awarded to Abraham Lincoln on May 22, 1849. Called "Buoying Vessels Over Shoals," Lincoln envisioned a system of waterproof fabric bladders that could be inflated when necessary to help ease a stuck ship over such obstacles. When crew members knew their ship was stuck, or at risk of hitting a shallow, Lincoln's invention could be activated, which would inflate the air chambers along the bottom of the watercraft to lift it above the water's surface, providing enough clearance to avoid a disaster. As part of the research process, Lincoln designed a scale model of a ship outfitted with the device. This model (built and assembled with the assistance of a Springfield, Ill., mechanic named Walter Davis) is on display at the Smithsonian Institution.[upper-alpha 1]

After reporting to Washington for his two-year term in Congress (beginning March 1847), Lincoln retained Zenas C. Robbins, patent attorney.[2][7] Robbins most probably had drawings done by Robert Washington Fenwick, his apprentice artist. Robbins processed the application,[2] which became patent No. 6,469 on May 22, 1849. However, it was never produced for practical use.[4][5] There are doubts as to whether it would have actually worked: It "likely would not have been practical," stated Paul Johnston, curator of maritime history at the National Museum of American History, "because you need a lot of force to get the buoyant chambers even two feet down into the water. My gut feeling is that it might have been made to work, but Lincoln's considerable talents lay elsewhere."[4]

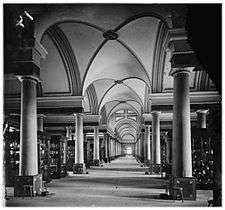

About that time, Lincoln took his son Robert Todd to the Old Patent Office Building[upper-alpha 2] model room to view the displays, sowing one of the youngster's fondest memories.[2] Lincoln himself continued to have a special affinity for the site.[upper-alpha 3]

Patent

The registered patent No. 6,469 starts,

| “ |

Be it known that I, Abraham Lincoln, of Springfield, in the county of Sangamon, in the state of Illinois, have invented a new and improved manner of combining adjustable buoyant air chambers with a steam boat or other vessel for the purpose of enabling their draught of water to be readily lessened to enable them to pass over bars, or through shallow water, without discharging their cargoes;[10] |

” |

Lincoln's patent ends with this claim,

| “ |

What I claim as my invention and desire to secure by letters patent is the combination of expansible buoyant chambers placed at the sides of a vessel with the main shaft or shafts C by means of the sliding spars or shafts D which pass down through the buoyant chambers and are made fast to their bottoms and the series of ropes and pullies or their equivalents in such a manner that by turning the main shaft or shafts in one direction the buoyant chambers will be forced downwards into the water and at the same time expanded and filled with air for buoying up the vessel by the displacement of water and by turning the shaft in an opposite direction the buoyant chambers will be contracted into a small space and secured against injury.[10]  |

” |

Lincoln's reflections on patents

Lincoln's exposure to the patent system, as an inventor and as a lawyer, engendered deep beliefs in its efficacy. In the United States, patent law has a constitutional foundation, was supported by the country's founders, and was viewed as an indispensable engine for economic development.[11] It led him to deliver two lectures on the subject, and was reflected in his approach as president.[12][13] Lincoln had an attraction to machinelike accessories all his life, which some say was hereditary and handed down to him from his father's interest in labor-saving equipment. He made speeches on inventions before he became president. He said in 1858, Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improves his workmanship.[4][5]

Lincoln admired the patent law system because of the reciprocal benefits it furnished both the inventor and society. In 1859 he noted that the patent system . . . has secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things.[5][14] He described the discovery of America as the most important development "in the world's history," followed second by the technology of printing and third by patent laws.[15] Lincoln was himself a patent lawyer.[12] Early in his legal career, he won an unreported patent infringement case for the defendant, styled Parker v. Hoyt. A jury found that his client's waterwheel did not infringe the patent. His second largest professional fee came from successful participation in the "Reaper Case", McCormick v. Manny. He was co-counsel for the defendant with two aggressive and preeminent Pennsylvania patent attorneys, George Harding, and Edwin M. Stanton. Although Lincoln was prepared and well-paid, his co-counsel thought him too "ungainly and unpresentable to be allowed to participate" and present the argument. Although he was sent home unheard, Manny won the case in an opinion authored by Supreme Court Judge John McLean.[16][17][18][19] Upon Lincoln's taking office, he offered Harding the job of Commissioner of Patents, which was refused. He later offered the position of United States Secretary of War to Stanton, who accepted and served.[2][20] Lincoln's final patent case was Dawson v. Ennis. It occurred between his presidential nomination and the election. His electoral triumph was juxtaposed with a litigation loss for his client.[1][2]

History of the model and letters patent

The original 1846 patent drawing was discovered in the United States Patent Office director's office in 1997. Its only omission is the usually required inventor's autograph in the lower right corner.[21] The Smithsonian Institution acquired about 10,000 patent models, including Lincoln's. The Engineering Collection includes about 75 maritime inventions; its Maritime Collections holds a replica, the original being deemed too fragile to loan. The National Museum of American History Political History Collections retains a copy of the patent papers.[21]

Bibliography

Footnotes

- ↑ There are contrary opinions as to the genesis of the model. One notes that the medal plaque affixed to it is misspelled as "Abram", a mistake not likely to be made by Lincoln himself. It concludes that it was likely made by a Washington model maker. Despite that, the Marine Collection curator thinks it is "one of the half dozen or so most valuable things in our collection."[4]

- ↑ A modern temple to rational invention patterned after the Parthenon.[8]

- ↑ In 1865, it was the venue for Lincoln's Second Inaugural Ball, the first ball held in a government building; twelve years later the upper floor was destroyed in the 1877 U.S. Patent Office fire.[9]

Endnotes

- 1 2 Goldsmith, Harry (January 1938). "Abraham Lincoln, Inventions and Patents". Journal of the Patent Office Society. 20: 5–33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dobyns, Kenneth W. (November 1994). "Chapter 25. Antebellum". The Patent Office Pony: A History of the Early Patent Office (1st ed.). Fredericksburg, VA: Sergeant Kirkland's Museum and Historical Society. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-9632137-4-7. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ↑ Emerson 2009, back cover, p. 114

- 1 2 3 4 5 Edwards, Owen (October 2006). "Inventive Abe: In 1849, a future president patented an ingenious addition to transportation technology". Smithsonian. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Lincoln's Patent". Abraham Lincoln Online. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ↑ Martin, Gary (1996). "Necessity Is the Mother of Invention". The Phrase Finder. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Lincoln's Patent" (PDF). American Civil War Anecdotes, Incidents, Articles, and Books. Skedaddle. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Patent Office". Scientific American. New York. XIV (32): 263–264. April 16, 1859. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican04161859-263. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ↑ Goodheart, Adam (July 2006). "Back to the Future: One of Washington's Most Exuberant Monuments—the Old Patent Office Building—Gets the Renovation it Deserves". Smithsonian: 4. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- 1 2 "Letters Patent No. 6,469". Google Patents. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Patent Law of the United States". Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- 1 2 Emerson 2009, p. 22

- ↑ "Lincoln the Inventor" (PDF). South Indiana University Press. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Abraham Lincoln, Second Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions". Jacksonville, IL: Illinois State Library. February 11, 1859. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ↑ Bellis, Mary. "A Patent for a President". Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ↑ McLean, John (1856). "Cyrus H. McCormick v. John H. Manny and Others". Reports of Cases Argued and Decided in the Circuit Court, Volume 6. H. W. Derby & Company. pp. 539–557 – via Google Books. (U.S. District Court of Ohio record)

- ↑ Emerson 2009, p. 22

- ↑ Hinchliff, Emerson (September 1940). "Lincoln and the 'Reaper Case'". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 33: 361–65.

- ↑ "The Manny Reaper: Some Background Information on the Case of McCormick v. Manny, 1855". Lincoln Lore: 1–4. June 1964.

- ↑ Emerson 2009, p. 21

- 1 2 "Abraham Lincoln's Patent Model: Improvement for Buoying Vessels Over Shoals". National Museum of American History. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

Further reading

- Emerson, Jason (2009). Lincoln the Inventor. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2898-7 – via Google Books.

- Parkinson, Robert Henry (September 1946). "The Patent Case that Lifted Lincoln into a Presidential Candidate". Abraham Lincoln Quarterly: 105–22.

External links

- U.S. Patent 6,469 - Manner of Buoying Vessels - Abraham Lincoln. 1849. (OCR scan of Lincoln's Patent application)

- Abraham Lincoln's Patent Model, National Museum of American History