Yam (vegetable)

Yam is the common name for some plant species in the genus Dioscorea (family Dioscoreaceae) that form edible tubers. Yams are perennial herbaceous vines cultivated for the consumption of their starchy tubers in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Oceania. The tubers themselves are also called "yams". There are many different cultivars of yams. Although some varieties of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) are also called "yam" in parts of the United States and Canada, the sweet potato is not part of the family Dioscoreaceae, but belongs in the unrelated morning glory family Convolvulaceae.

Description

Yams are monocots, related to lilies and grasses. Native to Africa and Asia, yam tubers vary in size from that of a small potato to over 60 kg (130 lb). Over 600 varieties of yams are known, and 95% of these crops are grown in Africa.[1]

- Differences between true yam and sweet potato "yam"

Yams are a monocot (a plant having one embryonic seed leaf) from the Dioscoreaceae family. Sweet potatoes are a dicot (a plant having two embryonic seed leaves) from the Convolvulaceae family. Therefore, they are about as distantly related as two flowering plants can be. Culinarily, yams are starchier and drier than sweet potatoes. The table below lists some differences between yams and sweet potatoes.[2]

| Factor | Sweet potato | Yam |

|---|---|---|

| Plant family | Morning glory | Yam |

| Chromosomes | 2n=90 | 2n=20 |

| Plant sex | Monoecious | Dioecious |

| Origin | Tropical America (Peru, Ecuador) | West Africa, Asia |

| Edible part | Storage root | Tuber |

| Appearance | Smooth, with thin skin | Rough, scaly |

| Shape | Short, blocky, tapered ends | Long, cylindrical, some with "toes" |

| Mouth feel | Moist | Dry |

| Taste | Sweet | Starchy |

| Beta carotene | Usually high | Usually very low |

| Propagation | Transplants/vine cuttings | Tuber pieces |

Yam tubers can grow up to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length[3] and weigh up to 70 kg (150 lb) and 7.6 to 15.2 cm (3.0 to 6.0 in) high. The vegetable has a rough skin which is difficult to peel, but softens after heating. The skins vary in color from dark brown to light pink. The majority of the vegetable is composed of a much softer substance known as the "meat". This substance ranges in color from white or yellow to purple or pink in mature yams.

Major cultivated species

Many cultivars of yams are found throughout the humid tropics. The most economically important are discussed below.[4]

D. rotundata and D. cayenensis

Dioscorea rotundata, the white yam, and D. cayenensis, the yellow yam, are native to Africa. They are the most important cultivated yams. In the past, they were considered as two separate species, but most taxonomists now regard them as the same species. Over 200 varieties between them are cultivated.

White yam's tuber is roughly cylindrical in shape, the skin is smooth and brown, and the flesh is usually white and firm. Yellow yam has yellow flesh, caused by the presence of carotenoids. It looks similar to the white yam in outer appearance; its tuber skin is usually a bit firmer and less extensively grooved. The yellow yam has a longer period of vegetation and a shorter dormancy than white yam.

The 'Kokoro' variety is important in making dried yam chips.[5]

They are large plants; the vines can be as long as 10 to 12 m (33 to 39 ft). The tubers most often weigh about 2.5 to 5 kg (5.5 to 11.0 lb) each, but can weigh as much as 25 kg (55 lb). After 7 to 12 months' growth, the tubers are harvested. In Africa, most are pounded into a paste to make the traditional dish of "pounded yam".[6]

D. alata

D. alata, called winged yam, water yam, and purple yam (not to be confused with the Okinawan purple "yam", which is a sweet potato), was first cultivated in Southeast Asia. Although not grown in the same quantities as the African yams, it has the largest distribution world-wide of any cultivated yam, being grown in Asia, the Pacific islands, Africa, and the West Indies.[7] Even in Africa, the popularity of water yam is second only to white yam. The tuber shape is generally cylindrical, but can vary. Tuber flesh is white and watery in texture.

In the Philippines, it is known as ube and is used as an ingredient in many sweet desserts. In Indonesia, it is known as ubi. In Vietnam, it is called khoai mỡ and is used mainly as an ingredient for soup. In India, it is known as ratalu or violet yam. In Hawaii, it is known as uhi. In Japan, it is called daijo or beniimo.

Uhi was brought to Hawaii by the early Polynesian settlers and became a major crop in the 19th century when the tubers were sold to visiting ships as an easily stored food supply for their voyages.[8]

D. polystachya

.jpg)

D. polystachya, Chinese yam, is native to China. The Chinese yam plant is somewhat smaller than the African, with the vines about 3 m (9.8 ft) long. It is tolerant to frost and can be grown in much cooler conditions than other yams. It is also grown in Korea and Japan.

It was introduced to Europe in the 19th century, when the potato crop there was falling victim to disease, and is still grown in France for the Asian food market.

The tubers are harvested after about 6 months of growth. Some are eaten right after harvesting and some are used as ingredients for other dishes, including noodles, and for traditional medicines.[6]

D. bulbifera

D. bulbifera, the air potato, is found in both Africa and Asia, with slight differences between those found in each place. It is a large vine, 6 m (20 ft) or more in length. It produces tubers, but the bulbils which grow at the base of its leaves are the more important food product. They are about the size of potatoes (hence the name "air potato"), weighing from 0.5 to 2.0 kg (1.1 to 4.4 lb).

Some varieties can be eaten raw, while some require soaking or boiling for detoxification before eating. It is not grown much commercially since the flavor of other yams is preferred by most people. However, it is popular in home vegetable gardens because it produces a crop after only four months of growth and continues producing for the life of the vine, as long as two years. Also, the bulbils are easy to harvest and cook.[6]

In 1905, the air potato was introduced to Florida and has since become an invasive species in much of the state. Its rapid growth crowds out native vegetation and is very difficult to remove since it can grow back from the tubers, and new vines can grow from the bulbils even after being cut down or burned.[9]

D. esculenta

D. esculenta, the lesser yam, was one of the first yam species cultivated. It is native to Southeast Asia and is the third-most commonly cultivated species there, although it is cultivated very little in other parts of the world. Its vines seldom reach more than 3 m (9.8 ft) in length and the tubers are fairly small in most varieties.

The tubers are eaten baked, boiled, or fried much like potatoes. Because of the small size of the tubers, mechanical cultivation is possible, which along with its easy preparation and good flavor, could help the lesser yam to become more popular in the future.[6]

D. dumetorum

D. dumetorum, the bitter yam, is popular as a vegetable in parts of West Africa, in part because their cultivation requires less labor than other yams. The wild forms are very toxic and are sometimes used to poison animals when mixed with bait. It is said that they have also been used for criminal purposes.[6]

D. trifida

D. trifida, the cush-cush yam, is native to the Guyana region of South America and is the most important cultivated New World yam. Since they originated in tropical rainforest conditions, their growth cycle is less related to seasonal changes than other yams. Because of their relative ease of cultivation and their good flavor, they are considered to have a great potential for increased production.[6]

Production

| Rank | Country | Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | | 38,000,000 |

| 2 | | 6,638,867 |

| 3 | | 5,674,696 |

| 4 | | 2,739,088 |

| 5 | | 864,408 |

| 6 | | 520,000 |

| 7 | | 460,000 |

| 8 | | 420,000 |

| 9 | | 345,000 |

| 10 | | 361,034 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organization [10] | ||

Yams are farmed on about 5 million hectares in about 47 countries in tropical and subtropical regions of the world.[11]

Yam crop begins when whole seed tubers or tuber portions are planted into mounds or ridges, at the beginning of the rainy season. The crop yield depends on how and where the setts are planted, sizes of mounds, interplant spacing, provision of stakes for the resultant plants, yam species, and tuber sizes desired at harvest. Small-scale farmers in West and Central Africa often intercrop yams with cereals and vegetables. The seed yams are perishable and bulky to transport. Farmers who do not buy new seed yams, usually set aside up to 30% of their harvest for planting the next year. Yam crops face pressure from a range of insect pests and fungal and viral diseases, as well as nematodes.[11]

Yams typically grow for 6 to 10 months and are dormant for 2 to 4 months, depending on the species. Their growth and dormant phases correspond respectively to the wet season and the dry season. For maximum yield, the yams require a humid tropical environment, with an annual rainfall over 1500 mm distributed uniformly throughout the growing season. White, yellow, and water yams typically produce a single large tuber per year, generally weighing 5 to 10 kg (11 to 22 lb).[4]

Yam production has low yield per hectare compared to crops such as cassava (manioc) or sweet potato. It is not an efficient food staple given the relatively large amount of planting material required and its long growing season. Yam's labor requirement exceeds that of other comparable crops. Yam is also difficult to preserve and store over extended periods of time. The cost per 1,000 calories of yam is four times greater than those of other root and tuber crops.[12]

For these reasons, the costs of yam production are high and yam crops are slowly losing ground to cassava and other food staples.

Despite these high costs and low nutrient density, when compared to other tubers and roots, low-technology yam farming produces the highest amount of food calorie and protein annually per hectare per season, on average. Given this nutritional value of yam and its high cultural acceptance in certain parts of Africa, interest exists in developing knowledge to improve yam agriculture.

In 2010, the world harvested 48.7 million tonnes of yam, 95% of which was produced in Africa. The biggest yam harvest, globally, was in 2008, when the world produced 54 million metric tonnes of yam.

The world average annual yield of yams was 10.2 tonnes per hectare in 2010. The most productive yam farms in the world were in Colombia, where nationwide average annual yield was 28.3 tonnes per hectare.[13] These are average national yields; certain farms report yields significantly above 30 tonnes per hectare, for example for yellow yam; other farms report yields less than 1 tonne per hectare.[14]

Despite the high labor requirements and production costs, consumer demand for yam is very high in certain subregions of Africa, making yam cultivation quite profitable to certain farmers.[11]

Harvesting

Yams in west Africa are typically harvested by hand using sticks, spades, or diggers.[14] Wood-based tools are preferred to metallic tools as they are less likely to damage the fragile tubers; however, wood tools need frequent replacement. Yam harvesting is labor-intensive and physically demanding. Tuber harvesting involves standing, bending, squatting, and sometimes sitting on the ground depending the size of mound, size of tuber, or depth of tuber penetration. Care must be taken to avoid damage to the tuber, because damaged tubers do not store well and spoil rapidly. Some farmers use staking and mixed cropping, a practice that complicates harvesting in some cases.

In forested areas, tubers grow in areas where other tree roots are present. Harvesting the tuber then involves the additional step of freeing them from other roots. This often causes tuber damage.

Aerial tubers or bulbils are harvested by manual plucking from the vine.

Yields may improve and cost of yam production be lower if mechanization were to be developed and adopted. However, current crop production practices and species used pose considerable hurdles to successful mechanization of yam production, particularly for small-scale rural farmers. Extensive changes in traditional cultivation practices, such as mixed cropping, may be required. Modification of current tuber harvesting equipment is necessary given yam tuber architecture and its different physical properties.[14]

Storage

Roots and tubers such as yam are living organisms. When stored, they continue to respire, which results in the oxidation of the starch (a polymer of glucose) contained in the cells of the tuber, which converts it into water, carbon dioxide, and heat energy. During this transformation of the starch, the dry matter of the tuber is reduced.

Amongst the major roots and tubers, properly stored yam is considered to be the least perishable. Successful storage of yams requires:[12][15]

- initial selection of sound and healthy yams

- proper curing, if possible combined with fungicide treatment

- adequate ventilation to remove the heat generated by respiration of the tubers

- regular inspection during storage and removal of rotting tubers and any sprouts that develop

- protection from direct sunlight and rain

Storing yam at low temperature reduces the respiration rates. However, temperatures below 12 °C (54 °F) cause damage through chilling, causing a breakdown of internal tissues, increasing water loss and yam's susceptibility to decay. The symptoms of chilling injury are not always obvious when the tubers are still in cold storage. The injury becomes noticeable as soon as the tubers are restored to ambient temperatures.

The best temperature to store yams is between 14 and 16 °C (57 and 61 °F), with high-technology-controlled humidity and climatic conditions, after a process of curing. Most countries that grow yam as food staple are too poor to afford high-technology storage systems.

Sprouting rapidly increases a tuber's respiration rates, and accelerates the rate at which its food value decreases.[12]

Certain cultivars of yams store better than others. The easier to store yams are those adapted to arid climate, where they tend to stay in a dormant low-respiration stage much longer than yam breeds adapted to humid tropical lands, where they do not need dormancy. Yellow yam and cush-cush yam, by nature, have much shorter dormancy periods than water yam, white yam, or lesser yam.

Storage losses for yams are very high in Africa, with insects alone causing over 25% harvest loss within 4 months.

Toxicity

Unlike cassava, most varieties of edible, mature, cultivated yam do not contain toxic compounds. However, there are exceptions.

Bitter compounds tend to accumulate in immature tuber tissues of white and yellow yams. These may be polyphenols or tannin-like compounds.

Wild forms of bitter yams do contain some toxins that taste bitter, hence are referred to as bitter yam. Bitter yams are not normally eaten except at times of desperation in poor countries and in times of local food scarcity. They are usually detoxified by soaking in a vessel of salt water, in cold or hot fresh water or in a stream. The bitter compounds in these yams are water-soluble alkaloids which, on ingestion, produce severe and distressing symptoms. Severe cases of alkaloid intoxication may prove fatal.

Aerial or potato yams too have antinutritional factors. In Asia, detoxification methods, involving water extraction, fermentation, and roasting of the grated tuber, are used for bitter cultivars of this yam. The bitter compounds in yams also known locally as air potato include diosbulbin and possibly saponins. These substances are toxic, causing paralysis. Extracts are sometimes used in fishing to immobilize the fish, thus facilitate capture. The community of Zulus use this yam as bait for monkeys, while hunters in Malaysia use it to poison wildlife such as tigers. In Indonesia, an extract of air potato is used in the preparation of arrow poison.[12]

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 494 kJ (118 kcal) |

|

27.9 g | |

| Sugars | 0.5 g |

| Dietary fiber | 4.1 g |

|

0.17 g | |

|

1.5 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

(1%) 7 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(10%) 0.112 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(3%) 0.032 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(4%) 0.552 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(6%) 0.314 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(23%) 0.293 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(6%) 23 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(21%) 17.1 mg |

| Vitamin E |

(2%) 0.35 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(2%) 2.3 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(2%) 17 mg |

| Iron |

(4%) 0.54 mg |

| Magnesium |

(6%) 21 mg |

| Manganese |

(19%) 0.397 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(8%) 55 mg |

| Potassium |

(17%) 816 mg |

| Zinc |

(3%) 0.24 mg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

The protein content and quality of roots and tubers is lower than other food staples. Of all roots and tubers, the protein content of yam and potato is the highest, being around 2% on a fresh-weight basis. Yams, with cassava, provide a much greater proportion of the protein intake in Africa, ranging from 6% in East and Sfrica to about 16% in humid West Africa.

Yam, like other root crops, is not a good source of essential amino acids. It is rich in phenylalanine and threonine, but limiting in the sulphur amino acids, cystine and methionine, and tryptophan. Yam-consuming areas of Africa have a high incidence of kwashiorkor, a serious medical condition in children caused by protein deficiency. Experts emphasize the need to supplement a yam-driven diet with more protein-rich foods to support active and healthy growth in infants.[16][17]

Except for potassium, vitamin B6 and vitamin C, yam has only moderate nutrient density.[18] Yam provides around 110 calories per 100 grams. It has good levels of potassium, manganese, thiamin, and dietary fiber, while being low in saturated fat and sodium. Yam generally has a lower glycemic index, about 54% of glucose per 150-gram serving, compared to potato products.[19]

The African yam contains thiocyanate; it was suggested in one paper that potentially it is protective against sickle cell anemia (SCA).[20] The paper points out that SCA is known to be relatively rarer in Africans than in the African-American population of the United States, and suggests that the higher thiocyanate content of the African diet explains the high incidence of SCA among African-Americans and its rarity in Africans.

Yam is an important dietary element for Nigerian and West African people. It contributes more than 200 calories per person per day for more than 150 million people in West Africa, and is an important source of income. Yam is an attractive crop in poor farms with limited resources. It is rich in starch, and can be prepared in many ways. It is available all year round, unlike other, unreliable, seasonal crops. These characteristics make yam a preferred food and a culturally important food security crop in some sub-Saharan African countries.[21]

Phytochemicals

The tubers of certain wild yam, a variant of kokoro yam and other species of Dioscorea, such as Dioscorea nipponica, are a source for the extraction of diosgenin, a steroid sapogenin. The extracted diosgenin is used for the commercial synthesis of cortisone, pregnenolone, progesterone, and other steroid products.[22] Such preparations were used in early combined oral contraceptive pills.[23] The unmodified steroid has estrogenic activity.[24]

Comparison to other staple foods

The following table shows the nutrient content of yam and major staple foods in a raw harvested form. Raw forms, however, are not edible and cannot be digested. These must be sprouted, or prepared and cooked for human consumption. In sprouted or cooked form, the relative nutritional and antinutritional contents of each of these staples is remarkably different from that of raw form of these staples.

| Nutrient component: | Maize / Corn[A] | Rice (white)[B] | Rice (brown)[I] | Wheat[C] | Potato[D] | Cassava[E] | Soybean (Green)[F] | Sweet potato[G] | Yam[Y] | Sorghum[H] | Plantain[Z] | RDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (g) | 10 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 79 | 60 | 68 | 77 | 70 | 9 | 65 | 3000 |

| Energy (kJ) | 1528 | 1528 | 1549 | 1369 | 322 | 670 | 615 | 360 | 494 | 1419 | 511 | 2000–2500 |

| Protein (g) | 9.4 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 12.6 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 13.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 11.3 | 1.3 | 50 |

| Fat (g) | 4.74 | 0.66 | 2.92 | 1.54 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 6.8 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 3.3 | 0.37 | |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 74 | 80 | 77 | 71 | 17 | 38 | 11 | 20 | 28 | 75 | 32 | 130 |

| Fiber (g) | 7.3 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 12.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 3 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 2.3 | 30 |

| Sugar (g) | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.78 | 1.7 | 0 | 4.18 | 0.5 | 0 | 15 | |

| Calcium (mg) | 7 | 28 | 23 | 29 | 12 | 16 | 197 | 30 | 17 | 28 | 3 | 1000 |

| Iron (mg) | 2.71 | 0.8 | 1.47 | 3.19 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 3.55 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 8 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 127 | 25 | 143 | 126 | 23 | 21 | 65 | 25 | 21 | 0 | 37 | 400 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 210 | 115 | 333 | 288 | 57 | 27 | 194 | 47 | 55 | 287 | 34 | 700 |

| Potassium (mg) | 287 | 115 | 223 | 363 | 421 | 271 | 620 | 337 | 816 | 350 | 499 | 4700 |

| Sodium (mg) | 35 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 15 | 55 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1500 |

| Zinc (mg) | 2.21 | 1.09 | 2.02 | 2.65 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.3 | 0.24 | 0 | 0.14 | 11 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | - | 0.08 | 0.9 | |

| Manganese (mg) | 0.49 | 1.09 | 3.74 | 3.99 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.40 | - | - | 2.3 |

| Selenium (μg) | 15.5 | 15.1 | 70.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.5 | 55 | |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.7 | 20.6 | 29 | 2.4 | 17.1 | 0 | 18.4 | 90 |

| Thiamin (B1)(mg) | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 1.2 |

| Riboflavin (B2)(mg) | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 1.3 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | 3.63 | 1.6 | 5.09 | 5.46 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.65 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 2.93 | 0.69 | 16 |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) (mg) | 0.42 | 1.01 | 1.49 | 0.95 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.80 | 0.31 | - | 0.26 | 5 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.62 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 0.3 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.29 | - | 0.30 | 1.3 |

| Folate Total (B9) (μg) | 19 | 8 | 20 | 38 | 16 | 27 | 165 | 11 | 23 | 0 | 22 | 400 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 214 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 180 | 14187 | 138 | 0 | 1127 | 5000 |

| Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol (mg) | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.14 | 15 |

| Vitamin K1 (μg) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.7 | 120 |

| Beta-carotene (μg) | 97 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 8509 | 83 | 0 | 457 | 10500 | |

| Lutein+zeaxanthin (μg) | 1355 | 0 | 220 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (g) | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.14 | |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (g) | 1.25 | 0.21 | 1.05 | 0.2 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.28 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.03 | |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g) | 2.16 | 0.18 | 1.04 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 3.20 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.07 |

| A yellow corn | B raw unenriched long-grain white rice | ||||||||

| C hard red winter wheat | D raw potato with flesh and skin | ||||||||

| E raw cassava | F raw green soybeans | ||||||||

| G raw sweet potato | H raw sorghum | ||||||||

| Y raw yam | Z raw plantains | ||||||||

| I raw long-grain brown rice |

Preparation

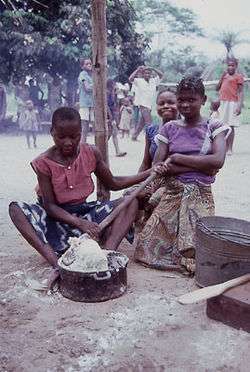

Africa

Yams of African species must be cooked to be safely eaten, because various natural substances in raw yams can cause illness if consumed. The most common cooking method in Western and Central Africa is by boiling, frying and roasting the yam.

Among the Akan of Ghana, boiled yam can be mashed with palm oil into eto in a similar manner to the plantain dish matoke, and is served with eggs. The boiled yam can also be pounded with a traditional mortar and pestle to create a thick, starchy paste known as iyan (pounded yam) or fufu which is eaten with traditional sauces such as egusi and palmnut soup.

Another method of consumption is to leave the raw yam pieces to dry in the sun. When dry, the pieces turn a dark brown color. These are then milled to create a brown powder known in Nigeria as elubo. The powder can be mixed with boiling water to create a thick starchy paste, a kind of pudding known as amala, which is then eaten with local soups and sauces.

Yams are a primary agricultural and culturally important commodity in West Africa, where over 95% of the world's yam crop is harvested. Yams are still important for survival in these regions. Some varieties of these tubers can be stored up to six months without refrigeration, which makes them a valuable resource for the yearly period of food scarcity at the beginning of the wet season. Yam cultivars are also cropped in other humid tropical countries.

Yam is the staple crop in Nigeria, where it is celebrated with yam festivals known as Iri-ji or Iwa-Ji depending on the dialect.

Philippines

In the Philippines, the purple ube species of yam (Dioscorea alata), is eaten as a sweetened dessert called ube halaya, and is also used as an ingredient in another Filipino dessert, halo-halo. It is also used as a popular ingredient for ice cream.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, the same purple yam is used for preparing a special type of soup canh khoai mỡ or fatty yam soup. This involves mashing the yam and cooking it until very well done.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the same purple yam is used for preparing desserts. This involves mashing the yam and mixing it with coconut milk and sugar. White- and off-white-fleshed yams are cut in cubes, cooked, lightly fermented, and eaten as afternoon snacks.

Japan

An exception to the cooking rule is the mountain yam (Dioscorea polystachya), known as nagaimo or yamaimo (山芋) depending on the root shape.

Nagaimo is eaten raw and grated, after only a relatively minimal preparation: the whole tubers are briefly soaked in a vinegar-water solution to neutralize irritant oxalate crystals found in their skin. The raw vegetable is starchy and bland, mucilaginous when grated, and may be eaten plain as a side dish, or added to noodles.

Another variety of yam, jinenjo, is used in Japan as an ingredient in soba noodles.

In Okinawa, purple yams (Dioscorea alata) are grown. This is known locally as daijo (大薯) or beniimo (紅芋). This purple yam is popular as lightly deep-fried tempura, as well as being grilled or boiled. Additionally, the purple yam is a common ingredient of yam ice cream with the signature purple color. Purple yam is also used in other types of traditional wagashi sweets, cakes, and candy.

India

In central parts of India, the yam (khamalu, suran, or chupri alu) is prepared by being finely sliced, seasoned with spices, and deep fried. In southern parts of India, known as karunai kizhangu (கருணைக்கிழங்கு) in Tamil, the vegetable is a popular accompaniment to rice dishes and fish curry. Also eaten in India, D. alata, a purple-pigmented species, is known as ratalu or violet yam.

In the southern part, especially in Kerala, both purple and white colored yams are locally known as kaachil or kavuttu.

In Karnataka, it is known as suvarna gadde. In central India, it is also called g.aradu In Andhra Pradesh, it is known as ganisi gadda.

Nepal

Dioscorea root is traditionally eaten on Māgh Sankrānti (a midwinter festival) in Nepal. In Nepali, it is called tarul and in Newari hī (ही). It is usually steamed and then cooked with spices.

The West

Yam powder is available in the West from grocers specializing in African products, and may be used in a similar manner to instant mashed potato powder, although preparation is a little more difficult because of the tendency to form lumps. The yam powder is sprinkled onto a pan containing a small amount of boiling water, and stirred vigorously. The resulting mixture is served with a heated sauce, such as tomato and chili, poured onto it.

Because of their abundance and importance to survival, yams were highly regarded in Jamaican ceremonies and constitute part of many traditional West African ceremonies.[26]

Cultural aspects

Nigeria and Ghana

A yam festival is usually held in the beginning of August at the end of the rainy season. People offer yams to gods and ancestors first, before distributing them to the villagers. This is their way of giving thanks to the spirits above them.

New Yam Festival

The New Yam Festival consists of prayers and thanks for the years past. Yam is the main agricultural crop of the Igbos, Idomas, and Tivs. It is the "staple" food of the Igbo people. The New Yam Festival, known as Orureshi in Owukpa in Idoma west and Ima-Ji, Iri-Ji or Iwa Ji in Igbo land is a celebration depicting the prominence of yam in the social and cultural life. The festival is very prominent among south-eastern states and all the major tribes in Benue state, mainly around August.

The celebration is followed by various cultural dance with the display of masquerades from different clans or groups. This usually last to very late night. During the occasion is also a moment of reuniting old friends and family members.

Traditionally, the "Feast of the New Yam" was held every year before the harvest began in many Igbo villages prior to colonialism. This feast was held to honor the earth goddess and the ancestral spirits of the clan. New yams could not be eaten until some had first been offered to these powers.

Elsewhere

Historical records in West Africa and of African yams in Europe date back to the 16th century. Yams were taken to the Americas through precolonial Portuguese and Spanish on the borders of Brazil and Guyana, followed by a dispersion through the Caribbean.[27]

Yams are used in Papua New Guinea, where they are called kaukau. Their cultivation and harvesting is accompanied by complex rituals and taboos. The coming of the yams (one of the numerous versions from Maré) is described in Pene Nengone (Loyalty Islands – New Caledonia).[28]

In many societies, yams are so important that one can speak of a 'yam civilization'. Growing the tuber is associated with magic; the best ones must be given to the chief or king; a series of myths is connected to a divine origin; a farmer may gain a lot of prestige by growing the largest or longest yam. Olhuala is a type of local yam that is a staple food in the Maldives.

On the Japanese island of Rishiri, yams and yam products are regarded as a folk remedy for the treatment of impotence, possibly because of the vegetable's high vitamin E content, but likely because of its evocation of virile phallic imagery, according to the common folk medicine theory of sympathetic medicine.

Etymology

From Portuguese inhame or Canarian (Spain) ñame, which are probably derived from some West African language, such as Fulani, Serer, Wolof, etc., many of which have verbs meaning "to eat", which could have been the source of the plant name that would have been borrowed.

Other uses of the term yam

Several other unrelated root vegetables are sometimes referred to as "yams", including:

- In the United States, sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), especially those with orange flesh, are often referred to as "yams". Firm varieties of sweet potatoes were produced before soft varieties. When soft varieties were first grown commercially, a need existed to differentiate between the two. African slaves had already been calling the soft sweet potatoes "yams" because they resembled the yams in Africa. Thus, soft sweet potatoes were referred to as yams to distinguish them from the firm varieties.[29] While sweet potatoes labeled as "yams" are widely available in supermarkets throughout the United States, markets that serve Asian or Caribbean communities often carry true yams. Today, the U.S. Department of Agriculture requires[30] sweet potatoes labeled with the term "yam" to be accompanied by the term "sweet potato."

- Just like commercial yams in the United States, Okinawan purple "yam" is actually a sweet potato.

- In New Zealand "yam" refers to the oca (Oxalis tuberosa),[31][32]

- The corm of the konjac - a Japanese vegetable with similar uses - is often colloquially referred to as a yam,[33] although it is unrelated.

- In Malaysia and Singapore, "yam" is used to refer to taro.[34]

See also

- Diosgenin, a precursor to many steroids (derived from yam species, notably Dioscorea villosa and Dioscorea composita[35]).

- Yam (disambiguation), for a variety of uses of the word yam

References

- ↑ "Everyday Mysteries: Yam". Library of Congress, United States of America. 2011.

- ↑ Schultheis and Wilson (1998). "What is the Difference Between a Sweetpotato and a Yam?". North Carolina State University.

- ↑ Huxley, 1992

- 1 2 Calverly (1998). "Storage and Processing of Roots and Tubers in the Tropics". Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations.

- ↑ Dumont, R.; Vernier, P. (2000). "Domestication of yams (Dioscorea cayenensis-rotundata) within the Bariba ethnic group in Benin". Outlook on Agriculture. 29: 137. doi:10.5367/000000000101293149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kay, D.E. (1987). Root Crops. Tropical Development and Research Institute : London

- ↑ Mignouna, H.D., Abang, M.M., & Asiedu, R. (2003). Harnessing Modern Biotechnology for Tropical Tuber Crop Improvement: Yam (Dioscorea spp.) Molecular Breeding. Available online.

- ↑

- White, L.D. (2003). Canoe Plants of Ancient Hawai'i: Uhi

- ↑ Schultz, G.E. (1993). Element Stewardship Abstract for Dioscorea bulbifera, Air potato. Nature Conservancy

- ↑ "Faostat". Faostat.fao.org. 2009-12-16. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- 1 2 3 "Yam". International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Oke (1990). "Roots, tubers, plantains and bananas in human nutrition". FAO. ISBN 92-5-102862-1.

- ↑ "Production crop data, Yams, 2010". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011.

- 1 2 3 Linus Opara (2003). "YAMS: Post-Harvest Operation" (PDF).

- ↑ "Roots, Tubers, and Plantains in Food Security: In Sub-Saharan Africa, in Latin America and the Caribbean, in the Pacific". FAO. 1989. ISBN 978-92-5-102782-0.

- ↑ "Kwashiorkor (Protein-Calorie Malnutrition)". Tropical Medicine Central Resource. 2006.

- ↑ "Undernutrition". The Merck Manual: The Home Health Handbook. 2010.

- ↑ Uwaegbute, Osho and Obatolu (1998). Postharvest technology and commodity marketing: Proceedings of a postharvest conference. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. p. 172. ISBN 978-978-131-111-6.

- ↑ "Glycemic index and glycemic load for 100+ foods". Harvard Health Publications, Harvard Medical School. 2008.

- ↑ Agbai, O., (1986). "Anti-sickling effect of dietary thiocyanate in prophylactic control of sickle cell anemia". Journal of the National Medical Association 78: 11.

- ↑ Izekor and Olumese (December 2010). "Determinants of yam production and profitability in Edo State, Nigeria" (PDF). African Journal of General Agriculture. 6 (4).

- ↑ Marker RE, Krueger J (1940). "Sterols. CXII. Sapogenins. XLI. The Preparation of Trillin and its Conversion to Progesterone". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 62 (12): 3349–3350. doi:10.1021/ja01869a023.

- ↑ Djerassi C (December 1992). "Steroid research at Syntex: "the pill" and cortisone". Steroids. 57 (12): 631–41. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(92)90016-3. PMID 1481227.

- ↑ Liu MJ, Wang Z, Ju Y, Wong RN, Wu QY (2005). "Diosgenin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human leukemia K562 cells with the disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis". Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 55 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1007/s00280-004-0849-3. PMID 15372201.

- ↑ "Nutrient data laboratory". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ↑ Jack Goody (1996). Cooking, Cuisine and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology. pp. 78–81. ISBN 978-0-521-28696-1.

- ↑ "Roots, tubers, plantains and bananas in human nutrition – Acknowledgments, Preface, Introduction, Origins and distribution". fao.org.

- ↑ Les ignames de Ma. YouTube. 11 February 2008.

- ↑ LOC.gov, What is the difference between sweet potatoes and yams?

- ↑ USDA.gov

- ↑ "...but in New Zealand we call them yams.", garden-nz.co.nz

- ↑ Albihn, P.B.E.; Savage, G.P. (June 18, 2001). "The effect of cooking on the location and concentration of oxalate in three cultivars of New Zealand-grown oca (Oxalis tuberosa Mol)". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 81 (10): 1027–1033. doi:10.1002/jsfa.890.

- ↑ "FDA bans more konjac products"

- ↑ "I yam not taro" Dr Lim Chin Lam, The Star

- ↑ Indian Herbal Pharmacopia Vol.II

Further reading

- Brand-Miller, J., Burani, J., Foster-Powell, K. (2003). The New Glucose Revolution: Pocket Guide to The Top 100 Low GI Foods. ISBN 1-56924-500-2.

- IITA has CGIAR global mandate for YAM. IITA's global research for development mandate.

- Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) (1994). A Breakthrough in Yam Breeding.

- Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) (2006). Yam.

- Hancock, J.F. (2003). Plant Evolution and the Origin of Crop Species. ISBN 978-0-85199-685-1.

- Holford, P. (1998). The Optimum Nutrition Bible. ISBN 0-7499-1855-1.

- Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan.

- Sumiyoshi, S., ed. (1996). Nigerian Culture and Customs: A Walk through Time. Koerner.

- Walsh, S. (2003). Plant Based Nutrition and Health. ISBN 0-907337-26-0.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Yam. |